People either get Cezanne, or they don’t. This grumpy Provencal workaholic was dubbed “the greatest of us all” by no less a figure than Claude Monet. Both Picasso and Matisse are said to have claimed him as “the father of us all”. Even today, artists of whatever stamp tend to doff their hats at the mere mention of Cezanne. His peerlessly incisive landscapes, still lifes and portraits offer us not only the roots of everything radical that has come since, from Cubism to conceptual art, but an uncompromising rigour that has set the gold standard for what the artist can and should be.

To the casual viewer, though, it can be hard to see what singles Cezanne out from the many other major and minor Post-Impressionist painters crowding the café tables of late 19th-century Paris. This eagerly awaited major survey opens with a trophy loan, The Basket of Apples, from the Art Institute of Chicago. Showing, well, a basket of apples, with some more apples spilt over a white cloth and an empty wine bottle, it’s a lovely painting. But it’s hard to imagine it as the starting point for the blasting apart of everything art had stood for over the previous 500 years.

The exhibition, however, still has 10 large rooms in which to make the case for Cezanne, offering us a new view of him, as both artist and man. In place of the awkward outsider figure of popular myth, who appeared oblivious to everything except the pursuit of the same few elusive “motifs” over decades, the exhibition wants to show us a warmer, more politically engaged Cezanne who was far from indifferent to “issues of modernity”.

While the show’s new contextual background is often fascinating – who knew he was an avid consumer of trashy popular magazines? – some of the connections are very speculative. Placing Cezanne’s extraordinary painting Scipio (1866-68), which shows the back of a Black model well known on the Paris art scene beside an engraving of the horrifically scarred back of a beaten slave, provides important context – we all inhabit the times we live in, whether we like it or not. Yet the idea that the abolition of slavery was an influence on Cezanne remains, as the show admits, only “possible”.

Indeed, the fact that he painted 29 portraits of his partner, later wife, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, may attest to their “continual closeness, rapport and partnership” – it’s certainly a testimony to her patience. But the two examples we’re shown do little to counter Cezanne’s own claim that he was interested in “bodies not souls”. In Madame Cezanne in a Yellow Chair (1888-90), the subject’s head is reduced to severely abstracted oval that looks forward to Picasso’s use of African masks in the world-changing Demoiselles d’Avignon. If it’s possible to detect a touch of tenderness in the set of her eyes and mouth, it’s certainly not something Cezanne himself was looking for.

Born into a solidly bourgeois background in Aix-en-Provence, Cezanne moved to Paris with his boyhood friend, the radical writer Emile Zola, aged 22. His most distinctive early paintings with their glistening, larded-on blacks are badly underrepresented. Only the melodramatic The Murder (1867-70) and a tiny still life, Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup (1865-70) give a flavour. But a group of early landscapes show the importance of Cezanne’s return to Provence, not only for him but for the future of art. This is where the show, like Cezanne’s art, starts to warm up.

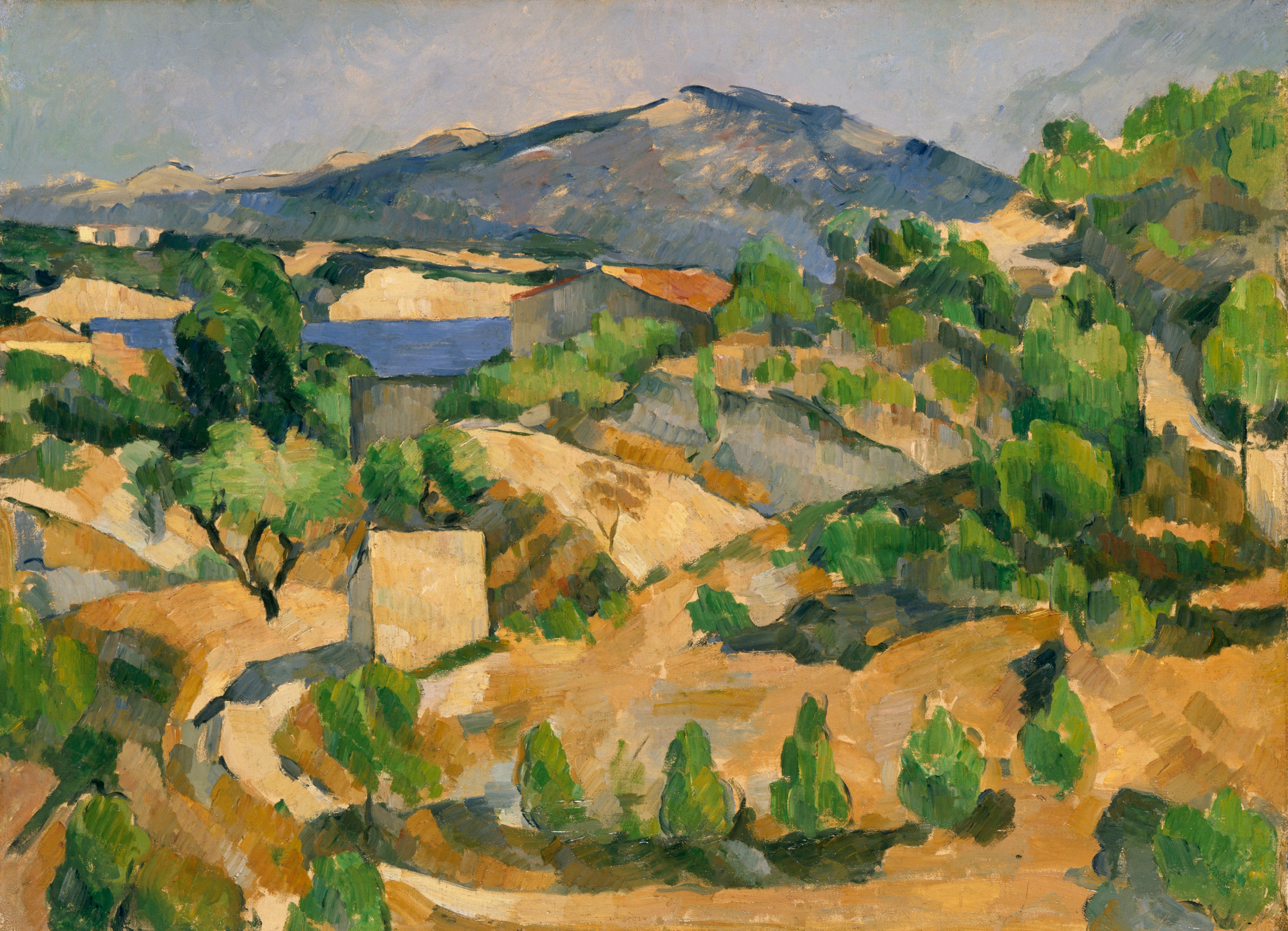

Paintings done in and around Paris, such as Auvers, Panoramic View (1873-75) have a drab, rainy-day-in-the suburbs look redolent of Cezanne’s early mentor, the great Impressionist Camille Pissarro. But in The Francois Zola Dam (1877-78) it’s as if an immense light has gone on – in the artist’s head as much as in his surroundings. The dam itself is barely visible, but angles and contours become harder and sharper in the blazing southern light, the spatial intervals between objects, such as the olive trees dotted over the parched earth, more precise. His earlier northern landscapes, indeed the whole of mainstream Impressionism, look grey and woolly in comparison.

It’s as though the moment he got off the train in Aix, Cezanne was hit by an urgency to “treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone”, as he famously put it. Paradoxically, and entirely typically, his desire to “make out of Impressionism something solid and durable like the art of museums”, led to the shattering of traditional notions of form and space.

In the second half of the show, we feel we’re coming much closer to Cezanne, as the focus narrows towards his “research”, as the exhibition calls it: his obsessive scrutiny of a few tightly defined subjects. Seeing several of Cezanne’s apparently endless still lifes of apples, stone jars and bits of cloth, you start to appreciate how he was glimpsing the universal, through minute variations in the form and gravitational weight of these objects and their relationships to the surrounding space.

In Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants (1893-94) the forms seem dry and hard, with a massive, stone-like solidity, while in Still Life with Apples, painted in the same year with many of the same objects, the light appears subtly adjusted so the scene takes on a barely definable radiance and luminosity.

Mont Sainte-Victoire, a limestone outcrop outside Aix, got under Cezanne’s skin to the extent he created 30 paintings of it. It seems to become more present, more potent in each of the seven paintings we’re shown, all dated 1904-06. The mountain is reduced to a glowing peak of almost Japanese simplicity in one, and seems to break down in the next into fragments of colour, as though abstract painting is being invented as we watch.

Cezanne’s “research” gives rise to another of Modern Art’s great ideas: the “series” as an end in itself. It’s a concept that projects us forward to Picasso and even to Warhol. Tate’s superb 2018 exhibition Picasso 1932 showed the Spanish painter, who was in many ways Cezanne’s great inheritor, relentlessly repeating images until he’d utterly exhausted them, and himself. Cezanne, however, doesn’t tire. A lifetime wasn’t long enough for everything he had to say about clusters of apples on tabletops or, indeed, another of his great compulsive projects, The Bathers.

What began as a youthful notion to create an imaginary composition using figures copied from other artists’ paintings and sculpture resulted in three monumental paintings. He was still working on them at the time of his death, endlessly shifting the abstracted figures around the canvases like immense girders. The one we’re shown here, on loan from the National Gallery (circa 1894-1905), feels at once very classical and so modern you’re left wondering if Picasso, the boy wonder of the next generation, was left with much to add to the deconstruction of human form.

Cezanne claimed to be in pursuit of “sensations”, feelings other artists – perhaps all people – experience, but which only he, he believed, had the courage to paint. He never attempted to put these feelings into words, as they were self-evidently embodied in the images he created. What you see is what he intended. That is it.

You get a sense of what this means in the final room as Cezanne, increasingly frail and diagnosed with diabetes, prior to his death aged 67, seems to simultaneously increase and reduce the volume of light in his paintings. It’s hard to tell in many of these works whether it’s day or night. But in the last of his still lifes and views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, forms take on a hallucinatory intensity as the artist tries to transcend the inevitable through the thing that meant most to him: work.

There’s a lot missing from this exhibition: not many, and certainly not the best, of the raw early paintings, and only a handful of the portraits, which are the place where you best see the proto-Cubist Cezanne. But if this show only gives us half the story, hell, what a half. If you’re remotely interested in painting – or, actually, just in art – you need to see this exhibition.

Tate Modern, until 12 March