Twenty-five years have passed since Rana was raped but she remembers like it was yesterday. It was 6pm on the 9 May 1992 when Serbian soldiers attacked her Bosnian village in Brcko District, burnt down hers and many of her neighbours’ homes and took her to a forest.

She recounts the day that changed her life forever, her hair neatly tied back, loop earrings and rimless glasses, suggesting an organised life but her scrambled thoughts tumbling out say otherwise.

“There were many soldiers in the field,” she remembers. “One of them told me to undress but I said no. He hit me and pushed me to the ground. It was the same man who had set fire to my house. Then he raped me. The other soldiers stood around and watched. He told them to rape me too and so I was raped again. Twice.”

The first rapist then put a knife to her throat. Another guy grabbed him shouting, ‘What are you doing? You have a sister’, adding it was better to let her live.

Kelima Dautovic was pregnant when war broke out. She thinks it saved her from the widespread sexual abuse in the Trnopolje concentration camp set up in a school in her hometown of Prijedor, Bosnia.

“They had their eyes set on teenage girls,” she says. “Many of the girls wore their father’s big shirts to cover their bodies. If you looked feminine or if they knew you previously and wanted sex they would just take you. Probably 10 were raped every night. They took them to a local empty house. The girls would come back the next morning totally exhausted but no one would talk about it. They were ashamed. We all knew silently what had happened but no one discussed it.”

No one knows how many girls and women were sexually abused during the genocide but the figures are huge. Estimates range from 20,000 to 50,000. Most of the rapists have since faced no prosecution or punishment but many of the victims still regularly see their rapists in the local neighbourhood.

Dr Branka Antic-Stauber currently counsels 150 women, many of whom have only recently revealed they were raped. She says some of the women have tracked the perpetrators down on Facebook. “They follow them to know where they are. One of my women knows the man’s birthday and the names and ages of his kids.”

Branka treats some who had children from their rapes. One gave her baby up for adoption as soon as he was born but took him back when he turned seven. It was a mistake. “She was beating the child every day,” Branka explains. We gave her psychological counselling but she beat the child one minute out of hatred and the next she would be crying out of remorse. They attended therapy for six years. Now the child is grown up and she’s finally a good mother. They’re at a point where they accept each other and their lives.”

But, according to the doctor, the men who fathered these children know nothing of them. “None have met their fathers nor have any of the men admitted what they did. If the rapist was to recognise the child he would recognise the crime and if that were the case he would be brought to court and sentenced for his crime.

Of the tens of thousands of these abuses just a handful of men have been found guilty in the last two decades. Branka believes much of that is due to a lack of political appetite: “Justice is so difficult to achieve, especially now that we have three divided political parties. The perpetrators on one side are seen as heroes and are protected because to their people they were on the right side and whatever they did was for their own people.”

The lack of retribution or acknowledgement of a crime is damaging and can hinder the healing process. Branka says, “Four men who raped eight girls, gang raped them, the women pointed to the men in court and said it was them, and there’s no doubt these women went through sexual abuse, but that’s not enough evidence to prosecute the perpetrators so they were released. Now they live just 20 kilometres from the men, just 10 minutes by car, and they know them because they’re just in the neighbouring town, but still these men were released to return to their homes. One of the women had a heart attack and died. The son of another of the women hanged himself. He couldn’t live with it.”

Rana gave an account of her ordeal to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. She believed the first man to rape her was a neighbour from her village but she was shown photos at the tribunal that were taken after the war and she didn’t recognise him.

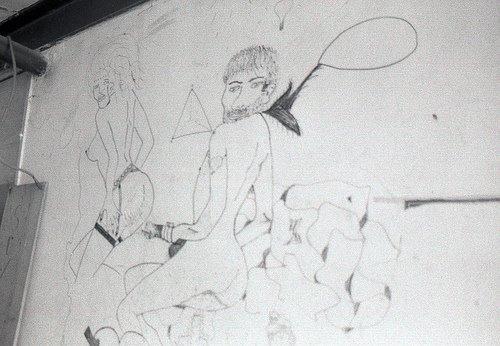

Women are, for the most part, strangely missing from the walls of the Srebrenica visitor centre in Potocari. The centre is on the site of the battery factory that served as the headquarters for the Dutchbat, the Dutch battalion between 1994-95 that has long been vilified for, despite being outnumbered and outgunned, doing nothing to stop the slaughter of more than 8,000 Muslim men. The most memorable female images were drawn in crude graffiti by the Dutchbat that either objectivise or insult. A number of the Dutch soldiers stationed there have since committed suicide. Others have since returned to Srebrenica to face up to their feelings of guilt.

Branka thinks the graffiti reveals much more than an attitude towards women. She feels it also betrays their fear. Ten years ago she organised a meeting between some of the soldiers and some of the female victims to try to heal both sides. “The women had questions,” she says. “They wanted to know why no one helped to save them. It was a UN-protected zone. So it meant a lot to the women to talk to the soldiers.”

Millions of dollars have been spent on the DNA project set up to try to identify the bones of those killed but very little has been done for those still reliving the torture and abuse. The state is failing these women.

Branka took it upon herself to develop what she calls an ecological rehabilitation that provides psychological, social, medical, legal and economic support. “They have so many social, psychological and economic problems,” she explains, “because we’re talking about women who went through torture when they were extremely young. None of them completed education, none of them were able to get a job, so their life passed totally marked by this traumatic event.” It’s often not until the women receive some sort of financial compensation for their trauma and they are no longer economically dependent on their husbands that they feel strong enough to speak out for the first time.

The women who find the courage still often face a culture of shame but they have a much greater chance of starting the healing process. Branka treats all three ethnic groups, the Bosniak, Croat and Serb, who are predominantly Muslim, Orthodox Catholic and Orthodox Christian, respectively. While Bosniaks were the most systematically abused, rape was used as a weapon of war by and against all sides. She says the Croat women are the most difficult to reach; “They don’t want to talk about it. They are dedicated to their faith and they believe only faith will help them find a way. Catholic priests are put through education to work with these women and the confession is the first psychotherapy. The depth of trauma is the same for all three religions but the social environment has a huge affect on the trauma. The family is the foundation and if the family accepts what has happened then the chance of the woman coming to terms with it improves drastically.”

Often the women have put their own suffering to one side. They talk about the number of men or children who were killed but when they categorise their own trauma they just say, “well, I lived”.

For the vast majority of the victims, the abuse is then compounded by a second trauma. “Ninety-five percent of the women are now victims of domestic abuse,” says Branka, “because their husbands cannot accept what happened to their wives. Even those who married a girl knowing she had been abused will repeat this abuse.”

Rana is one of them. Her husband would justify this domestic abuse by telling her that if he hadn’t married her no one else would have. It proved too much and in 1997 she attempted suicide. She still struggles with immense sadness: “I feel I am dead even though I’m not really dead. I often wish I had died that day. The only comfort I can find is in telling myself that I am not alone. I talk to other women who have been through the same thing and see how they are coping with it. If I’m busy at work then I can forget sometimes. But the most vivid memories in my life are the ones from that day.