We didn’t have kids, yet. So with plenty of time to burn, my wife and I sat on the sofa and worked through Nick Bantock’s “Griffin & Sabine,” the 1991 illustrated novel whose love story unfolds, quite literally, in a series of postcards and letters.

I admit that “Griffin & Sabine” has not come to mind much in the third of a century since. Not until recently, when I found myself strolling with the curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Newberry Library, Suzanne Karr Schmidt, through the exhibit she created, “Pop-Up Books through the Ages.”

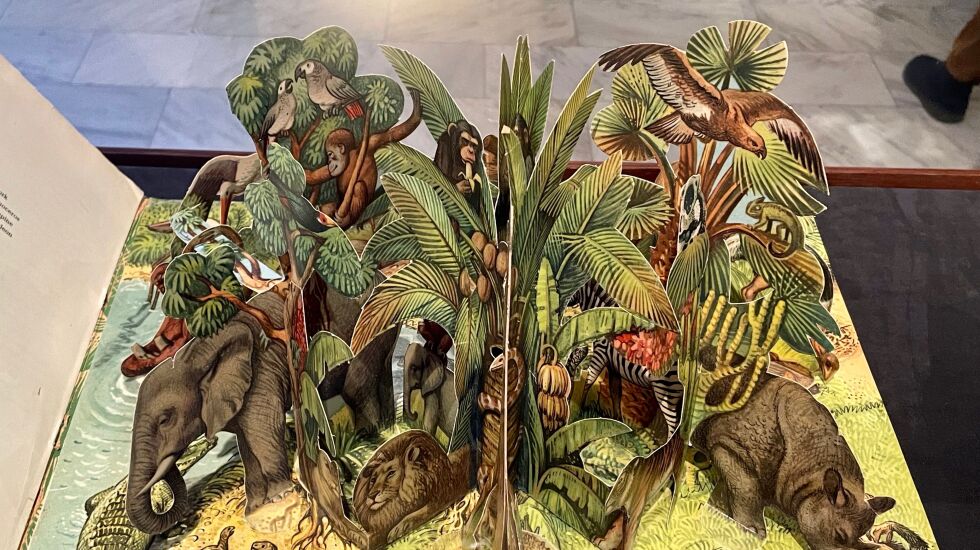

With the exception of freakish epistolary adult best-sellers — “Griffin & Sabine” and its sequels sold millions of copies — pop-up books today are considered primarily a niche entertainment for children, where colorful three-dimensional contrivances rear out of pages as they’re opened.

But the Newberry’s books, some nearly a millennium old — the oldest dates to 1121 — have dials and flaps showing calendars and cosmos, anatomical studies, and a town before and after a landslide. (Though several reveal a discreetly hidden naked lady).

“The interactiveness of it makes the show fun,” Karr Schmidt said.

I was surprised, looking at these amazing volumes, how often the technological wonder in my back pocket came to mind. We often sneer at our phones, for good reason. But when you see the lengths scholars and clerics went to in the past, trying to visualize information, it makes you appreciate what we have. We’re living their unattainable dream.

“A lot of these books do many of the things that a screen does now,” Karr Schmidt said.

“Pop-Up Books through the Ages” is particularly kid-friendly, with large pages of cut out dolls and offers a souvenir pop-up Newberry Library, created for the exhibit by Chicago illustrator Hannah Batsel and paper engineer Shawn Sheehy.

Grab one, and notice the little wooden barrel, a wink at the story of the library’s founder, Walter Newberry, expiring on a sea voyage in 1868 and being returned in a barrel filled with rum. I admire any organization unafraid of depicting its founder in such an undecorous position. They’ve printed 5,000 pop-up libraries and are giving them away.

“We are flying through them,” said Karr Schmidt, noting that the show, which opened in mid-March, has been particularly well-attended. (I should probably mention that I’m a scholar-in-residence at the Newberry, though whether that biases me toward them, or is just a humble brag, I’ll leave for you to decide).

“It was groundbreaking for us,” she said. “People want to go out and see things again.”

The show runs through July 15 and was a good fit for Karr Schmidt, who wrote her dissertation at Yale on the renaissance pop-up book.

“I’ve been thinking about this material a long time,” she said.

What draws a person to become an expect in renaissance pop-up books?

“How far back do you want to go?” she asked. “I grew up in Washington, D.C., surrounded by museums. I always wanted to work with interesting objects. Printed materials are one way you could make discoveries.

“There are boxes of things in European collections that nobody has gone into for 50 years. Suddenly you find a ‘The pope is the devil’ flap print nobody has paid attention to. Propaganda. Erotica. A lot of innovative ways people used material.”

The TikTok of its time, flap prints were a way to supposedly reveal the true nature of someone — a pious friar can, with a quick flip, be turned into a debauchee.

She used a phrase — “the materiality of things that are printed” — that I like. Books do indeed have a solid physical quality that computers can’t match. If I wanted to access something from a computer in 1991, I’d face a mute stack of floppy discs.

But books endure. I knew “Griffin & Sabine” had to be somewhere, and after a brief inspection of every blessed book spine in my office, I found it, literally at my feet, on a long shelf I tucked under my computer table.

“Hey,” I asked my wife. “Do you want to re-read ‘Griffin & Sabine’ tonight?”

“Sure!” she said. “That would be great.”

After dinner, we sat on the sofa. She rested her head on my shoulder while I read, opening envelope flaps and unfolding the letters within, as the enigmatic South Seas muse and the too solitary London artist sound each other out. A vast improvement over just sitting there, staring at our phones.