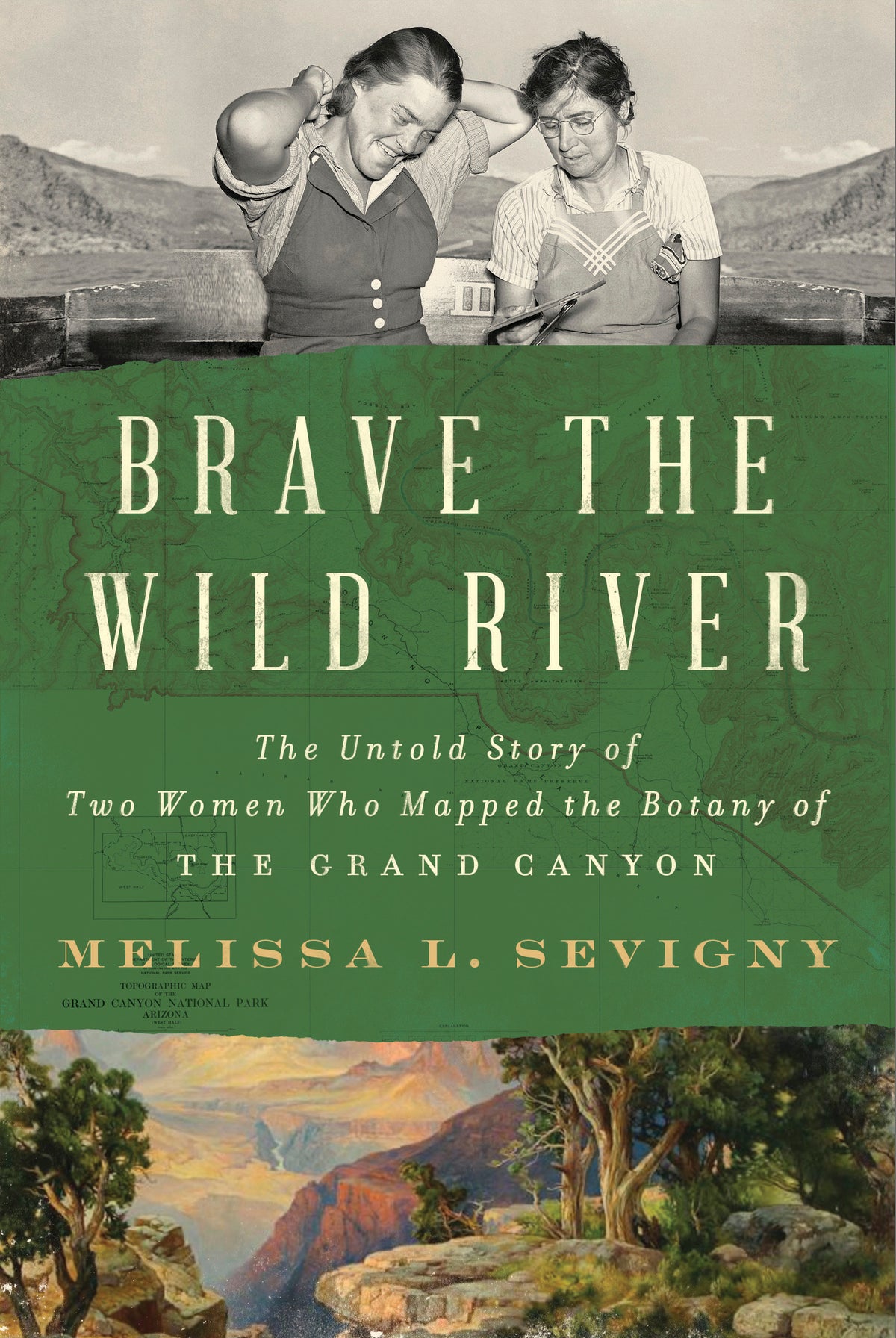

“Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon” by Melissa L. Sevigny (W. W. Norton & Company)

Long before climate change threatened the very existence of the Colorado River, two women botanists set off with a group of amateur boatman to record the plants that lived along what was then the most dangerous river in the world.

In “Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon,” science journalist Melissa L. Sevigny draws on the diaries of Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter to trace their 43-day sojourn in the summer of 1938.

The bookish Jotter, then 23, joined Clover, an old school but stylish scientist who was then 41. They were the only women on the small excursion to “botanize” the Grand Canyon. Well publicized by newspapermen who suggested the trip was inappropriate and dangerous for women, stories written at the time underscored how females were then viewed and diminished.

“Two Women to Risk Lives for Science in Colorado Canyon,” was the headline on one story in the Minneapolis Tribune.

As women, Jotter and Clover were expected to cook all the food on the trip, for instance, and they seemed to do so without complaint.

Carried past sheer cliffs and along sometimes treacherous rapids, the trailblazing women risked their lives to record the flora of a little-known pocket of the American West just as it starting to be transformed by the early influence of human beings in the area.

But once the trip began, they focused on the task of collecting and cataloguing all the plants they came across, from beavertail and hedgehog cacti to Thompson's wooly locoweed, a low creeping plant with fuzzy pink seed pods on purplish stems.

There was also Rocky Mountain juniper and Mormon tea, a shrub of bluish green stalks sprouting tiny cones at its joints. And, of course, there was plenty of Russian thistle, better known as tumbleweed, which was accidentally introduced from Russia in the 1870s in bushels of flaxseed and went on to become an iconic symbol of the American west.

Every night, the women pressed the plants between pages of newspaper, slicing the cacti in half and scooping out the pulp first.

Along the way, there was heat, hunger and fatigue, along with “mosquitoes the size of dinner plates,” wrote Sevigny. They got blisters on hands and feet, and cuts and bruises everywhere on their bodies.

And there was real danger, starting with the stomach churching Mile-Long Rapid, which had ended several expeditions before theirs.

Now a reporter for Arizona Public Radio, Sevigny grew up in Tucson, where she fell in love with the Sonoran Desert landscape and ecology. The natural world is also the focus of her earlier books, “Mythical River” (University of Iowa Press, 2016); and “Under Desert Skies” (University of Arizona Press, 2016).

“Brave the River” also highlights the little-known contributions two women made to our knowledge about the Southwest ecology. And it pays homage to a pair of scientists far ahead of their time.