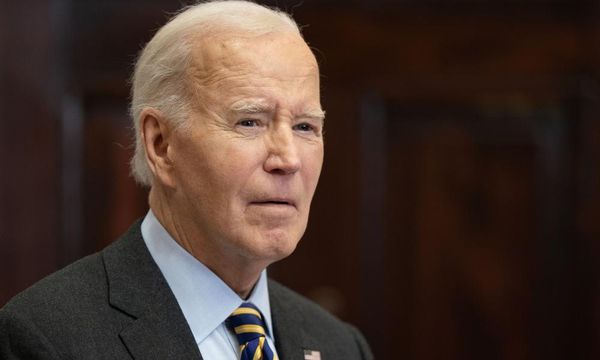

Linda Thomas-Greenfield, U.S. President Joe Biden’s nominee to serve as ambassador to the United Nations, struck a combative tone on China during her confirmation hearing last month, describing Beijing as a “strategic adversary” whose disdain for human rights and democracy “threaten our way of life.”

But the veteran U.S. diplomat may now have to win over Beijing in order to secure diplomatic wins in her first weeks at Turtle Bay.

If confirmed, Thomas-Greenfield will have to muster global support for key global challenges at the U.N., including the fight to contain the coronavirus pandemic and global warming. China’s backing or at least acquiescence will be critical.

During the past year, the Trump administration’s efforts to blame China and the World Health Organization for mishandling the pandemic in its earliest stages led to diplomatic deadlock at the U.N. The emergence of highly contagious variants of COVID-19 that have been rapidly spreading across national borders provides an opportunity to test China’s willingness to cooperate in a global effort to contain it.

“I think there is space to make some early moves by the administration on COVID and climate,” said Richard Gowan, a U.N. expert with the International Crisis Group.

“The Trump administration approach to China in the [Security Council] over COVID was so absurdly offensive that Biden just needs to lay out some common sense plan on the pandemic and to see if the Chinese are willing to come on board,” he added. “My instinct is there is probably room for cooperation on COVID with the Chinese and the Russians.”

Even before the inauguration, Biden’s U.N. transition team recommended an ambitious campaign for the administration to reassert its role as a leader at the world body, by rejoining key U.N. institutions including the U.N. Human Rights Council and taking bold action at the Security Council to demonstrate U.S. leadership on COVID-19 and climate change, according to three sources familiar with the plan who didn’t want to be identified discussing confidential recommendations. The team also floated the idea of having Biden host a U.N. Security Council meeting in March, when the United States assumes the presidency of the 15-nation council. It’s unclear whether the new administration will move forward on those proposals.

Among the recommendations was a plan to pass a U.N. Security Council resolution with a series of practical measures aimed at helping nations cope with the health crisis. The idea was to model the measure roughly on a September 2014 resolution that sought to coordinate the international response to the Ebola outbreak in the West African nations of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, and warned that the outbreak “continues to constitute a threat to international peace and security.”

The Ebola resolution, which the United States played a key role in drafting, urged governments and U.N. agencies to help supply and train medical workers, provide medical equipment, and lower trade and travel restrictions to allow foreign health workers and medicines into the affected countries.

“Ours was an all-hands-on-deck public health, logistic and diplomatic campaign to get countries to pool their resources to prevent hundreds of thousands of infections in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and the spread of the deadly disease around the world,” Samantha Power, the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations who led the Ebola negotiations, wrote in April 2020 for the New York Times.

Power is now Biden’s pick to lead the U.S. Agency for International Development. In a more recent piece in Foreign Affairs, she argued that the United States should spearhead the global distribution of COVID-19 vaccines to restore international confidence in the U.S. expertise and competence, which has been undercut by the Trump administration’s mishandling of the pandemic in the United States. “The United States can reenter all the deals and international organizations it wants, but the biggest gains in influence will come by demonstrating its ability to deliver in many countries’ hour of greatest need,” she wrote.

At the same time, the Biden administration has criticized China for covering up information about the origins of COVID-19, which was first detected in Wuhan, China, in late 2019. The U.S. recently expressed skepticism over claims by a World Health Organization team that the virus may have originated outside of China, citing the need to send U.S. health experts to China to learn how the pandemic started.

In his first conversation on Wednesday with China’s President Xi Jinping, Biden struck a stern tone, voicing concern about China’s conduct on the world stage.”President Biden underscored his fundamental concerns about Beijing’s coercive and unfair economic practices, crackdown in Hong Kong, human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and increasingly assertive actions in the region, including towards Taiwan,” according to a White House statement. Biden said on Twitter that he also told Xi “I will work with China when it benefits the American people.”

Biden has already recommitted the United States to international institutions, including the World Health Organization and the U.N. Human Rights Council—where the Americans recently offered their support to a European resolution condemning the military coup in Myanmar. His administration has also pledged to support an international program known as COVAX that is designed to get vaccines to the most vulnerable in small and midsize countries that lack the financial wherewithal to secure contracts from major pharmaceutical companies.

But other issues will have to wait till Thomas-Greenfield is confirmed. Republican Sen. Ted Cruz has delayed her nomination, citing questions about her willingness to take a tougher stance on China and its expanding influence at the U.N. It now appears unlikely that she will be confirmed before Feb. 22, when the Senate is expected to complete impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump—and about a week before the United States assumes the council presidency.

“This is one of the many reasons we’ve been advocating for her confirmation as soon as possible,” said one administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The U.S. has an important leadership opportunity at hand. We need her to be able to engage on our national security priorities immediately.”

The United States has been in ongoing discussions with the British and French on a resolution that would expand the U.N.’s role in delivering badly needed vaccines to people in conflict zones.

Britain’s Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab will host a Feb. 17 U.N. Security Council virtual meeting on global vaccine distribution, offering an opportunity for U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken to participate in his first U.N. debate. The foreign ministers of China and India have already agreed to participate in the meeting. Britain holds the rotating presidency of the council this month.

U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson is scheduled to follow up with a high-level virtual Security Council meeting on Feb. 23 to discuss climate change in advance of a major climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, later this year. It appears likely that either Biden, Blinken, or perhaps the president’s new climate envoy, John Kerry, will participate in that meeting, though the United States has made no firm commitment.

There is still some debate within the Biden administration on whether it makes more sense to build on the British initiatives in the U.N. Security Council, or to pursue U.S. policies on climate and COVID-19 in other institutions like the World Health Organization—or at a series of high-level meetings, including an April 22 climate summit to be hosted by Biden and a May 21 G-20 Summit in Rome.

The dilemma underscores the complexity of U.S. relations with China, and the broader effort to reinvigorate multilateral institutions like the United Nations. On the one hand, Biden and his U.N. envoy-designate have made it clear they intend to counter China’s efforts to expand its influence at the U.N., and to call Beijing out on its abuse of human rights from Xinjiang to Hong Kong. But the reality is that very little can be achieved in the 15-nation council without the agreement of China and Russia, which both wield veto power over any council decisions.

“It’ll take skillful U.S. diplomacy to simultaneously reach out for PRC support over global issues like COVID and climate, while pushing China on … human rights and democratic values in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong,” said Courtney Fung, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Still, U.N. observers and China watchers believe the United States can gain the support of the Chinese without having to give up anything in return, and win some goodwill from allies and other council members.

“It’s a no-brainer,” Gowan added. “Trump needlessly offended good allies at the U.N. and Biden has a very straightforward chance to remake friendships and win some credibility by showing he wants to relaunch cooperation on COVID and climate.”

Elizabeth Economy, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, said the United States should move early to carve out a leadership position on climate in advance of the November Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

“This could include new more ambitious targets for CO2 reduction by all major emitters, agreements for assistance to developing economies, and proposals for coordination in areas such as carbon border taxes and emissions trading,” Economy told Foreign Policy.

“This is not a moment when the United States needs to offer China something in exchange for doing more. Depending on the level of ambition by the Biden administration, the pressure will be on China to raise its game, for example by halting its program of financing and exporting coal-fired power plants.”