After five months mired in the day-to-day grind of a struggling presidential campaign, the El Paso massacre shook something loose in Beto O’Rourke.

Two days after the shooting, which was carried out by a white supremacist who was motivated by what he called an Hispanic invasion, O’Rourke was in his hometown surrounded by a sea of reporters. Someone asked him how President Donald Trump should respond; O’Rourke was having none of it.

“He’s been calling Mexican immigrants rapists and criminals. Members of the press, what the fuck?” O’Rourke implored. “It’s these questions that you know the answers to. I mean, connect the dots about what [Trump’s] been doing in this country. He’s not tolerating racism; he’s promoting racism. He’s not tolerating violence; he’s inciting racism and violence in this country.”

It was these sorts of unfiltered, from-the-gut responses that animated his 2018 Senate campaign and made him a political folk hero in Texas and across the country. It was also the sort of thing that seemed to be far less common as O’Rourke tried to figure out how to be a top-tier presidential contender.

After spending more than a week grieving with his fellow El Pasoans, O’Rourke emerged to recast his presidential bid as an expression of that “what the fuck?” sentiment. In a speech earlier this month, he declared that he was now running with the primary purpose of confronting Trump and his willful provocation of racial violence. Trump is a racist, a white supremacist, and an all-consuming threat to the country, he said. “I’m confident that if at this moment, we do not wake up to this threat, then we, as a country, will die in our sleep,” he declared, pledging to take up the mantle of anti-racism, of immigrants, and of gun control.

O’Rourke is at his best when speaking about these issues. But he’s often refrained from treating his political opponents as, well … opponents. He is far more comfortable employing the rhetoric of unity and a greater good than of confrontation and an inherent evil. This is, after all, the same guy who mostly refrained from beating up on Senator Ted Cruz, one of the most loathsome political figures in the country. After invoking Cruz’s nickname of “Lyin’ Ted” in a debate, he later said that the mild insult might have been “a step too far.” In December, he told reporters that he has “never run against somebody or against something,” and wouldn’t do so as a presidential candidate. “I’m just not a negative guy. I’m not turned on by bringing other people down.”

But after the El Paso shooting, O’Rourke’s ebullient political outlook has become decidedly foreboding. “In the immediate term, [Trump] is the greatest threat to this country, bar none,” he told the New York Times. Beto said he couldn’t just return to the banalities of the campaign trail, like the “corn dogs and ferris wheels” at the Iowa State Fair. Instead, he pledged to visit the places most directly impacted not just by Trump, but also by the country’s long history of racial violence.

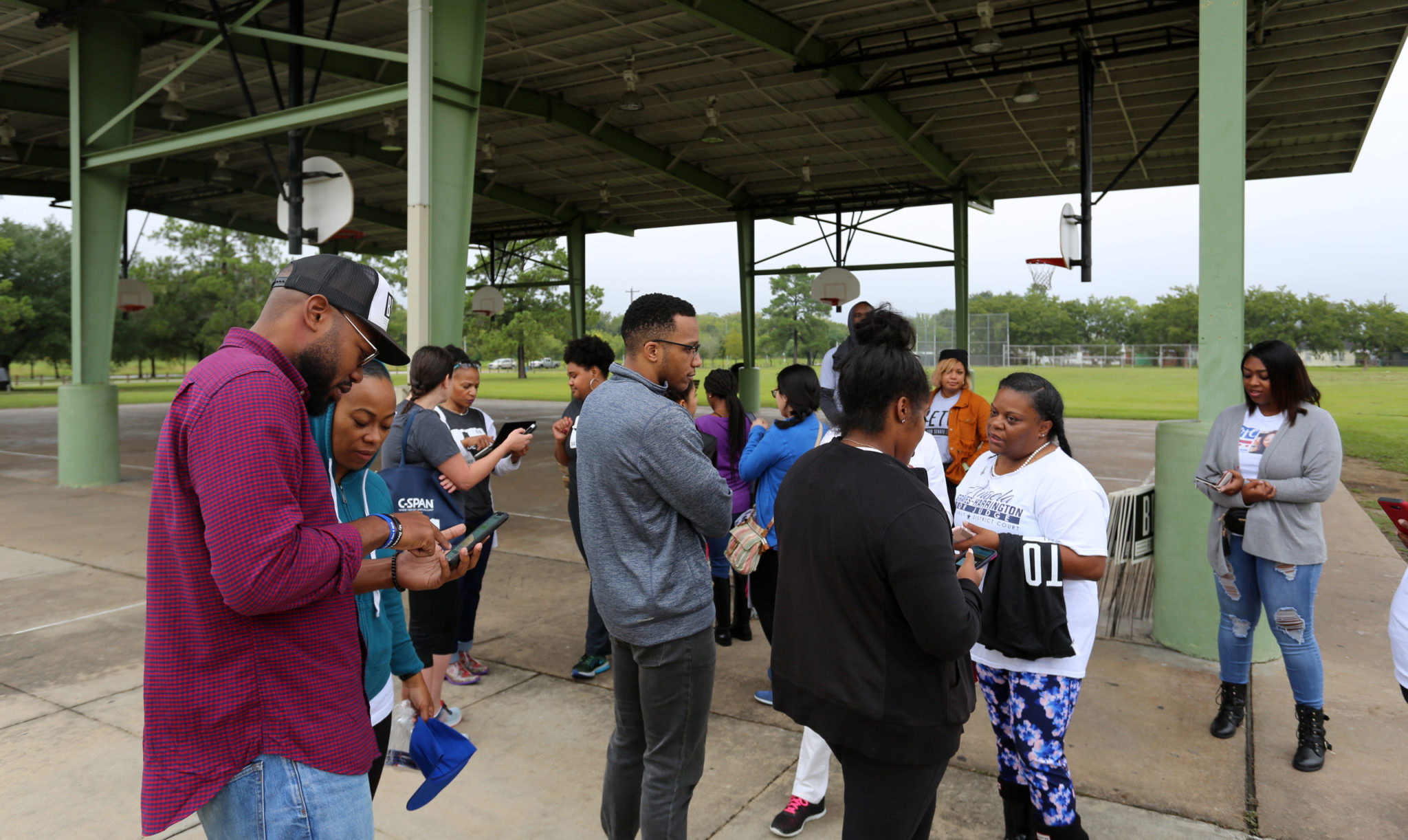

In the days since his speech, O’Rourke has traveled to Mississippi where Trump’s ICE agents raided a workplace and detained nearly 700 Hispanic workers, to a gun show in Arkansas to talk about gun control and mandatory assault rifle buybacks, and to Oklahoma, where he toured the site of the Tulsa race massacre in 1921 and the Oklahoma City bombing memorial. Going to these places was his way to “connect the dots” between Trump and the country’s history. “Not only are we as divided as we’ve ever been, but the racism that has been foundational to this country has now been admitted out into the open. And people are acting on that,” he said in Tulsa last Monday. He began this week in South Carolina before heading to North Carolina and Virginia, including Charlottesville, where, two years ago, the Unite the Right rally turned deadly and ushered in a newly emboldened white nationalist movement.

By making Trump’s racism, guns, and immigration the central focus of his presidential campaign and traveling to states that are usually ignored in the primaries, O’Rourke is leaving behind the conventional, inside-the-lines approach that has resulted in his consistent polling below 3 percent.

The spontaneous, just-do-what-feels-right shift—the kind that tends to give campaign operatives and donors the cold sweats—is a callback to the sort of anti-conformist political instincts that helped elevate him to the presidential race in the first place. Indeed, the most compelling argument for Beto’s presidential bid was that he would take the singular style of his Senate run—the DIY spirit, the prohibition of consultants and pollsters, the large-scale organizing, the small-donor fundraising machine—and nationalize it.

But that romantic notion quickly gave way to an utterly standard presidential campaign. As political operatives insisted, it was preposterous to think that what (almost) worked in Texas would also work in the complex terrain of a crowded presidential primary. Order must be imposed.

So O’Rourke hewed to the standard presidential primary playbook. He took the advice offered by former President Barack Obama and hired Jen O’Malley Dillon, who was deputy campaign manager for Obama in 2012, to run his campaign. A well-respected operative practiced in the art of building top-down national campaigns that have won, she set up a traditional campaign infrastructure and beefed up the staff with other well-respected party operatives. The campaign operated in a typical fashion, pouring resources—and O’Rourke’s time—into the early primary states of Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina. O’Rourke abandoned the backbone of his innovative 2018 run, namely the massive distributed organizing program that granted volunteers a certain amount of autonomy. Becky Bond and Zack Malitz, the alums of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign who built and oversaw that program and were committed to scaling it up nationwide for O’Rourke’s presidential run, exited the campaign soon after O’Malley Dillon came on.

But O’Rourke’s attempted transformation from barnstorming underdog into bona fide presidential contender never really took hold. Despite his blue-chip campaign team, the former congressman quickly found himself fading to the background, oftentimes indistinguishable from any of the other numerous middling candidates. While he raised an astounding $6.1 million in the 24 hours after announcing his presidential campaign, his fundraising has since tanked—he only pulled in $3.6 million during the three months that followed, far behind most candidates.

The quaint days of “Will he or won’t he?” are long gone, replaced with a growing chorus of “Why did he?” He’s been hounded by persistently low-single-digit polling numbers, and his two debate performances have been rather lackluster. Along the way, he’s been branded as egotistical and entitled, unprepared and unfocused, as a political lightweight and a Trojan horse for centrism. He’s no longer the Democratic darling, to say nothing of the next Obama; O’Rourke is now the tragic underachiever.

The calls increased for him to drop out and run for Senate again in Texas.

O’Rourke firmly ruled that out in El Paso. “[That] would not be good enough for this community. That would not be good enough for this country,” he insisted. “We must take the fight directly to the source of this problem.”

So will this earnest crusade jumpstart his campaign? O’Rourke is by no means unique in his absolute condemnation of Trump, nor in his redoubled emphasis on combating racism and xenophobia. But as the field begins to winnow down, his reworked message of urgency may start to break through, especially at the upcoming debate in his home state. Still, one thing is for sure: He is once again veering off the beaten path. As his political career has shown, that’s usually where he thrives.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Governor Abbott Swaps One Scandal-Scarred Secretary of State for Another: As Texas Workforce Commission chair, Ruth Hughs secretly coordinated with tech lobbyists to rewrite the rules of the gig economy. Now she’s in charge of state elections.

-

Could Trump’s Reelection Campaign Turn the Texas House Blue?: A number of high-profile GOP electeds are throwing in the towel in advance of the 2020 election cycle—with more expected in the coming year.

-

Water Wars Pit Rural and Urban Texas Against Each Other: Fast-growing North Texas towns need water. But a reservoir project will displace families who have lived in Fannin County for generations.