AUSTIN, Texas — The office is packed with memorabilia from a lifetime of golf. Trophies, including two from his Masters victories. Photos and clubs and ball markers and golf balls. Just about anything related to the game.

And there are books. Lots of books. More than 400 of them, with subjects ranging from architecture and the game’s various improvements, to instruction, biographies, tournament programs, long-ago players and courses.

Yes, Ben Crenshaw has always been fascinated by the game’s past, going back to his earliest competitive days. He soaked up golf history before making it himself.

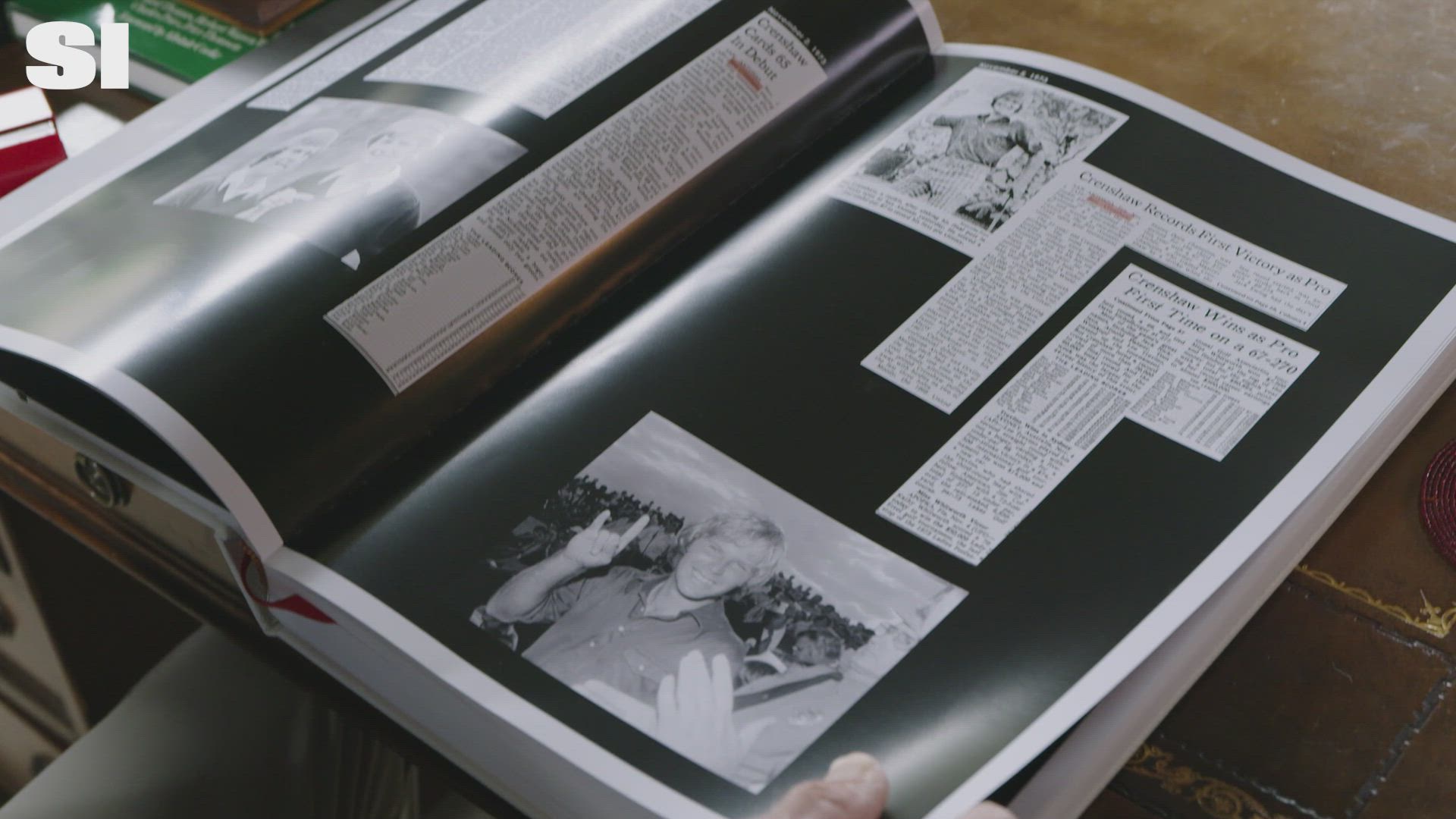

Among his various keepsakes is a scrapbook that includes the Feb. 11, 1974, issue of Sports Illustrated with Crenshaw on the cover and the headline “Make Way for the Kid.” Crenshaw was 22 years old.

The story was penned by legendary writer Dan Jenkins, who covered golf and college football at SI, among other things, for many years.

Crenshaw was the bright new star in the game, having won the Texas Open in his first start as a member of the PGA Tour followed by a runner-up finish a week later.

Jenkins’s story, on page 32, was titled “Gentle Ben is Very Tough.”

All these years later, Crenshaw, now 73, who went on to win the Masters twice as well as 19 PGA Tour titles, is sheepish about it. He remained in touch with Jenkins throughout the rest of the writer’s life (Jenkins died in 2019).

“I’d met him at Colonial in Fort Worth,” Crenshaw says during an interview in his home. “Of course he lived in Fort Worth. And I’d run across him at the Masters. My first year was 1972. I just loved seeing him. A great Texan. He took a liking to me because of the fans we had. He was a great friend of Darrell Royal, our University of Texas football coach here. And it was just always good to see him.

“I was a pretty good shill for him. He made fun of me all the time, for which I loved him. We talked about friends, football. We talked about [Ben] Hogan stories. Nobody loved talking more about Ben Hogan than Dan Jenkins. He was just hilarious. And such a gifted writer. Nobody could write like him. Fantastic.”

It is the rare athlete who takes an interest in those writing about them, but Crenshaw always did and continues to rattle off various authors or writers whose works he loved or admired.

Crenshaw recalled meeting Herbert Warren Wind for the first time when he played in a junior tournament at age 16. Wind is the writer who coined the phrase “Amen Corner”—the intersection of holes 11, 12 and 13 at Augusta National—in a 1958 SI story, the year Arnold Palmer won the Masters for the first of four times.

“Where it all started for me was when I was 16 years old,” Crenshaw says. “At the Country Club in Boston [Brookline, Mass.] for the [U.S.] Junior Amateur. I met people that week I would play with for the rest of my life. I fell in love with the place. Fell in love with the golf course. Fell in love with the competition. And golf history.

“I really enjoyed learning golf history. And I just felt I was so lucky to be able to play this place in Boston where Francis Ouimet won the 1913 U.S. Open as an amateur. I really had an affinity for that place. It stemmed from my appreciation for golf and appreciation for places and people.”

Crenshaw’s chance meeting with Wind led to further dealings including a time the writer went to Texas to profile Harvey Penick, the golf instructor who worked with Crenshaw and fellow Austin golfer Tom Kite from their earliest days until the teacher’s death on the eve of the 1995 Masters—which Crenshaw won 30 years ago, leading to his second SI cover.

Penick, whose best-selling Little Red Book has sold more than one million copies and is still in circulation today, had a big influence on Crenshaw’s career.

And it is why Wind’s visit still resonates.

“He did a wonderful story on him,” Crenshaw says. “Apart from his writing at Sports Illustrated, he was writing for the The New Yorker. And he would implore his editors to give him more space. He wrote such beautiful, lucid, long, meaty articles that were just filled with … it was the kind of writing that you had to have a thesaurus right next to you. To me, people like that gave me more appreciation of this game and its people.”

Crenshaw grew up at Austin Country Club and became friends and rivals with Kite, with whom he would attend the University of Texas. Crenshaw won three consecutive NCAA individual titles—sharing one of them with Kite—and won nine other prestigious amateur titles.

After turning professional, Crenshaw first had to make it through what today is called the PGA Tour Qualifying Tournament in order to have access to the weekly events.

He won it by 13 shots.

In his first event after winning Q-School, Crenshaw won the Texas Open and its $25,000 first prize. The following week, he finished second at the eight-round World Open at Pinehurst, banking another $44,000.

It was around this time that the cover story for SI began to take shape, although Crenshaw wasn’t aware of it. In fact, he did not know it was happening until he saw the actual magazine with his face on the cover.

“I can’t remember how this happened,” he says. “All of a sudden I saw me on this thing. ‘Make Way for the Kid.’ That’s a lot to say. I was feeling great and confident. But it’s a lot to put on you. I was just enjoying it. Enjoying the competition. And enjoying playing tournament golf. Seeing what I could do and have some success with it.

“I was surprised a little bit. People knew what kind of person I am. It was just fun to see people’s reactions. And how far I could stretch myself. I felt like I could accomplish a lot back then. When I would see the professionals, I remember [longtime Tour pro] Dave Hill. He always gave me the business: ‘You’re going to come down hard some day.’ I took a lot of kidding, which was great. I enjoyed playing with those guys. It was part of my golfing education. I just tried to soak up everything I could.”

By the time of the SI story, Crenshaw had already played in six major championships, having finished at low amateur at the 1972 and 1973 Masters. He was also the low amateur at the 1970 U.S. Open his first major.

Jenkins’s story gushed that Crenshaw was golf’s newest star.

“Charm, charisma, appeal,” he wrote. “Some golfers have it built in, like a [Arnold] Palmer or Lee Trevino, and others acquire it, as [Jack] Nicklaus and Ben Hogan did, by winning. Crenshaw undoubtedly has it built in, Palmer style, but he appears to be starting out with even more golfing ability than Palmer had.”

High praise … and then Crenshaw didn’t win for two years.

“I didn’t quite think I lived up to some of his [Jenkins’s] words,” Crenshaw says. “I was so young. And just brand new. I was a kid.”

A jinx, perhaps?

“There were a cadre of people who subscribed to that theory,” he says. “I had big highs and then lows. And had to climb out of it, just like a lot of golfers. Golf is a fickle game. When you have a good feel and you’re confident, you feel like you can do something. If you get down and miss a couple of cuts in a row, you start searching.

“I would come back and see Harvey Penick. He could tell that I was listening to some people who would suggest things in my swing. And he would politely say just trust in your ability. You want to believe that. He was right.

“You just realize that you’re better off taking care of your own ability and working with that. Learning how to be patient. Learning how to score. Learning how to play courses better. That temptation to cut across is lethal.”

Crenshaw’s patience paid off. It took until January 1976 before he won again, capturing the Bing Crosby Pro-Am at Pebble Beach, the first of three victories that year.

By 1984, he had won nine times on the PGA Tour and had five runner-up finishes in majors, including a playoff loss to David Graham at the 1979 PGA Championship. In all, he had 16 top-10s in the game’s biggest tournaments, and “the kid” who had been on the SI cover a decade earlier was still without one of the biggest prizes.

Pressure mounted.

“History is filled with really capable players who never won a major. And I was close in many,” Crenshaw says. “You start wondering. And it gnaws on you, no question. You feel like you’re capable but you don’t get it across. That’s the mentality you’re in. You really have to be patient somehow. It was such a relief to win that first Masters in 1984. It was humongous. I felt I had it in me. But until you see it right in front of you, you’ve got to somehow prove it.”

Crenshaw shot a final-round 68 to finish two strokes ahead of Tom Watson and win his first major and 10th PGA Tour title.

But the following year, Crenshaw went through a divorce and after several months was diagnosed with a hyperactive thyroid gland. He lost weight and his game.

Slowly, he began to regain form. He remarried in 1985—he and his wife, Julie, celebrate their 40th anniversary this year and have three daughters. And his game came back, too.

He won five times from 1986 to 1990 and also had a few more close calls in the majors, with seven top-seven finishes. In 1987, he was top seven in all four.

The major success waned in the early 1990s but he added three more victories on the PGA Tour before his improbable Masters win in 1995, which came just days after Penick died.

Crenshaw and Kite left Augusta National to attend Penick’s funeral in Austin, where they served as pallbearers the day before the Masters began. Penick was 90 and had been in poor health but his death still elicited immense sadness and emotion.

“I tried not to think about it when I was back at Augusta,” Crenshaw says. “But this was a man who had given us our love for the game and meant so much to so many people and passed away. Suddenly, I had this calm and peace. I’m at my favorite place. In New Orleans (the week prior), I saw some good signs even though I missed the cut.”

Carl Jackson, Crenshaw’s longtime caddie at Augusta National, noticed something in the golfer’s swing. He told Crenshaw to move the ball back slightly in his stance and make a tighter shoulder turn behind the ball.

“I started hitting the ball solidly in a short period of time,” he says. “I went out with those two simple thoughts the first day and it went beautifully. Second day, nice. Third day, nice. Saw some really good things happening on and around the greens.

“Still not trying to think about what happened. It was like my mind went back to being a kid. “I was just playing, unfurled. And had great fortune.”

Crenshaw shot 68 in the final round to hold off Davis Love III by a stroke, dropping his putter on the 18th green and sobbing alongside Jackson. Reliving the story has Crenshaw emotional again, a second victory at the place he loves the most on top of the personal loss was finally too much to keep inside.

It was the last victory of his Hall of Fame career, one that would not see him win again but did include a victory as U.S. Ryder Cup captain four years later as the Americans staged the biggest final-day comeback in the event’s history.

Along the way, Crenshaw forged a successful golf course design business along with partner Bill Coore, with dozens of courses around the world. When home, he ventures out to Austin Golf Club.

As a past champion, Crenshaw will be back at the Masters, where he presides over the annual Tuesday night Champions Dinner and typically holds court. He will be there for the 54th straight year.

“I haven’t missed a year,” he says. “I’ve adored everything about it. Everything about it is in honor of the game.”

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Ben Crenshaw, Golf’s Gentleman, Feels the Game’s History Like No Other Champion.