Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s budget on Wednesday, November 22 will put into place a major piece of the Conservative party’s strategy for the general election – the plan to turn the economy around and tackle the cost of living crisis. But with just over a year to go before an election must be called, will the measures be too little, too late?

The government certainly derived some satisfaction from last month’s fall in the UK rate of annual inflation to 4.6%, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak quickly taking credit for meeting his target to halve the rate in 2023. Nonetheless, economic prospects look grim.

The Bank of England is predicting growth of just 0.5% this year, zero next year and just 0.25% in 2025. To some extent, this is likely to be self-inflicted, with the bank saying it will keep interest rates high for at least another year to ensure inflation falls to its target of 2%.

Neither will people’s incomes make up the difference. Wage growth has just caught up with inflation, but this has far from compensated for the fall in real incomes since the pandemic. And with taxes the highest in decades as a share of the economy, there is growing pressure within the Conservative party for a pre-election tax cut.

Reviving the economy

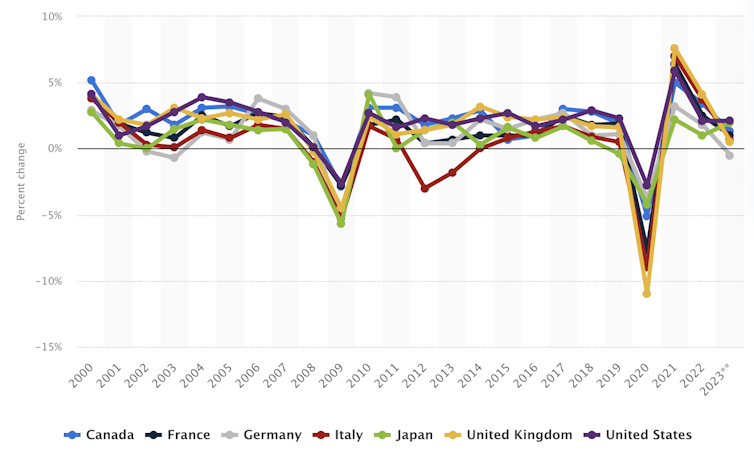

The UK economy has in fact been flatlining for a decade, with low growth and little increase in household incomes. Relative to competitor countries, there is less business investment, a less well-trained workforce, and failure to complete big infrastructure projects such as HS2 - all leading to lower productivity.

GDP growth of G7 major economies

The chancellor has said he wants to make this a budget for growth, and plans to help business with much of his £13 billion “fiscal headroom” (the amount that can be spent without increasing government debt as a share of GDP). This will include extending the temporary tax relief on business investment, costing £10 billion a year.

Hunt has also pledged £4.5 billion over five years to support strategic manufacturing sectors including green energy. And he may exempt more small businesses from VAT.

The government’s problem is a lack of consistency. Businesses need long-term certainty to plan future investments. But since the Conservatives came to power in 2010, taxes on business have been cut, then raised, then cut and then raised again, with several different exemptions for investment. There have also been seven different chancellors and nine different business secretaries.

Cutting taxes and cutting benefits

The chancellor and prime minister have given a clear signal that they are minded to cut taxes, but in a manner that doesn’t drive up inflation.

One idea widely floated in the media would be to cut inheritance tax, which currently raises £7 billion a year. This would be less inflationary than cutting income tax, but would only benefit around 27,000 wealthy taxpayers a year.

Another possibility would be to cut stamp duty to help revive the ailing housing market.

Cutting income tax or national insurance would be more politically attractive than these options, of course. And this may well come, but perhaps not put in place until the spring budget, assuming inflation continues ticking down.

To fund his tax-cutting plans, Hunt is also weighing up ways of cutting the growing benefits bill. Firmly in his sights are those on sickness or disability benefit, whose numbers have increased sharply in recent years.

He has already announced a new system of assessing people’s ability to work and a £500 million “back to work plan” to provide more support to those with mental or physical health issues.

Despite the war on “scroungers” who supposedly don’t want to work, it is not clear how much, or how quickly, the Exchequer will benefit. Hunt might be tempted to try another approach with more immediate results.

Working-age benefits are currently planned to be increased in April by 6.7%, in line with the inflation rate in September. By cutting the increase to the current 4.6% inflation rate, the chancellor could save £3 billion.

Although less likely, there is also talk of Hunt trying to change the calculation for the state pension – which is linked to earnings – by excluding bonus payments.

Fiscal rules and the spending squeeze

One thing the chancellor is unlikely to announce is an increase in spending on hard-pressed public services. He has already rejected a plea from the NHS for extra funding, saying it should meet the increased wage bill by another 0.5% of “efficiency savings”.

You might wonder how to reconcile this with the £13 billion “fiscal headroom” mentioned earlier. It’s because Hunt will only have that amount to play with if there’s an impossibly tight squeeze on public spending for the next five years.

In 2021, public spending was slated to increase at 1% a year in real terms. But the subsequent effect of inflation now means the same plans amount to a significant cut in today’s money.

The other reason the chancellor has headroom is that tax receipts have been growing more rapidly than expected, lowering the projected deficit. However, this is mainly due to higher inflation.

And assuming the government does adjust its public-spending plans to factor in inflation, it could cancel out most of the gains in tax revenues in years to come. Higher inflation, and the higher interest rates it has led to, has also sharply increased the amount the government must spend on debt repayments, which now cost more than the education budget.

Labour’s dilemma

Labour’s desire to demonstrate that it’s fiscally responsible and on the side of working people has created the potential for Hunt to lay several traps for them.

Given the importance of the NHS as an issue for Labour, can they accept the impossibly tight spending plans if they form the next government? And having opposed the recent rise in national insurance contributions, will they find it difficult to oppose any proposed cut?

Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves has made it clear she will not support tax cuts for the rich, nor accept reductions in how benefits are calculated – but she has not said she would reverse such moves. Labour has made it clear that more money on public services will have to come from higher growth.

If Labour’s charm offensive can convince business they have a consistent, long-term growth strategy, they may reap the rewards. Turning around the British economy has never been either quick or easy for any government, however.

Steve Schifferes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.