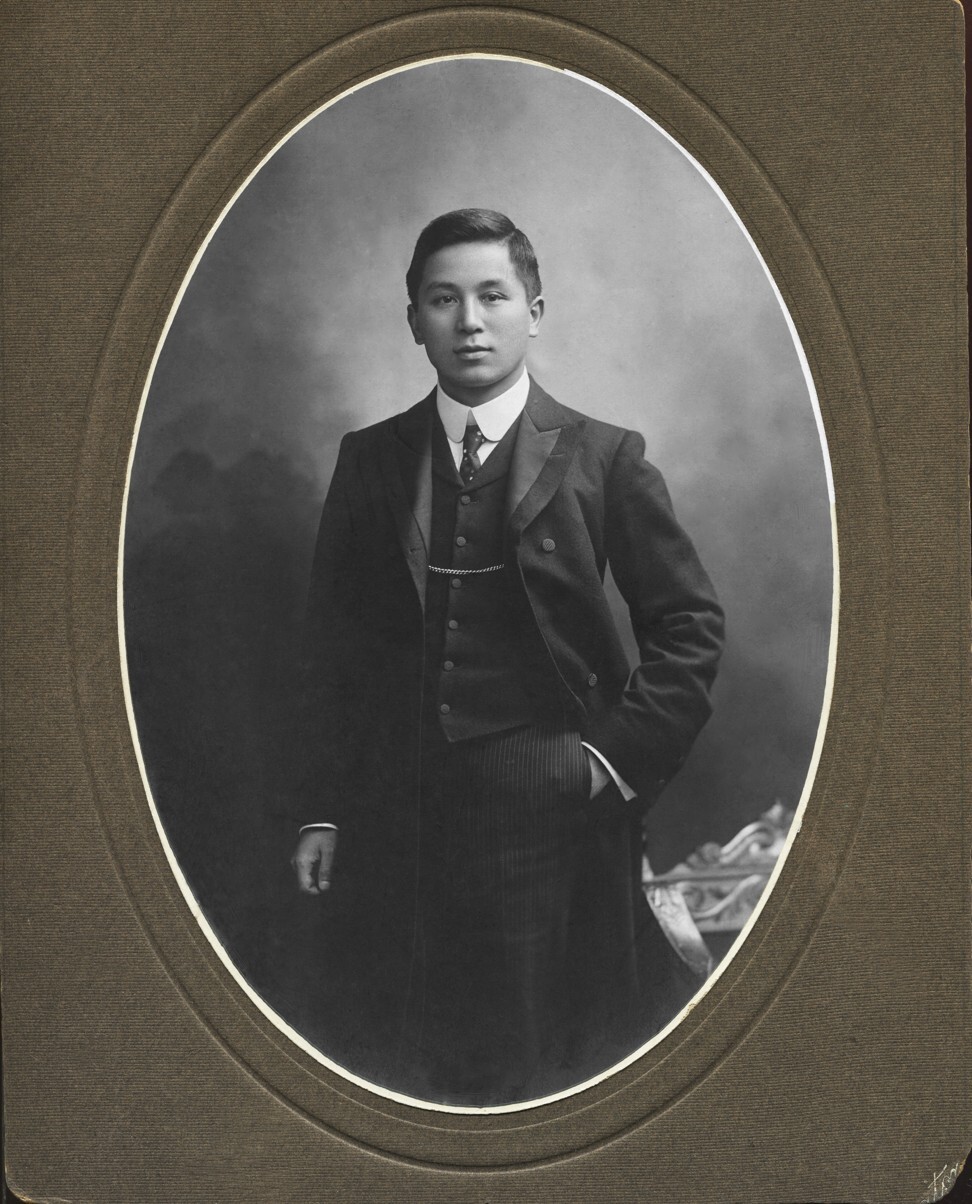

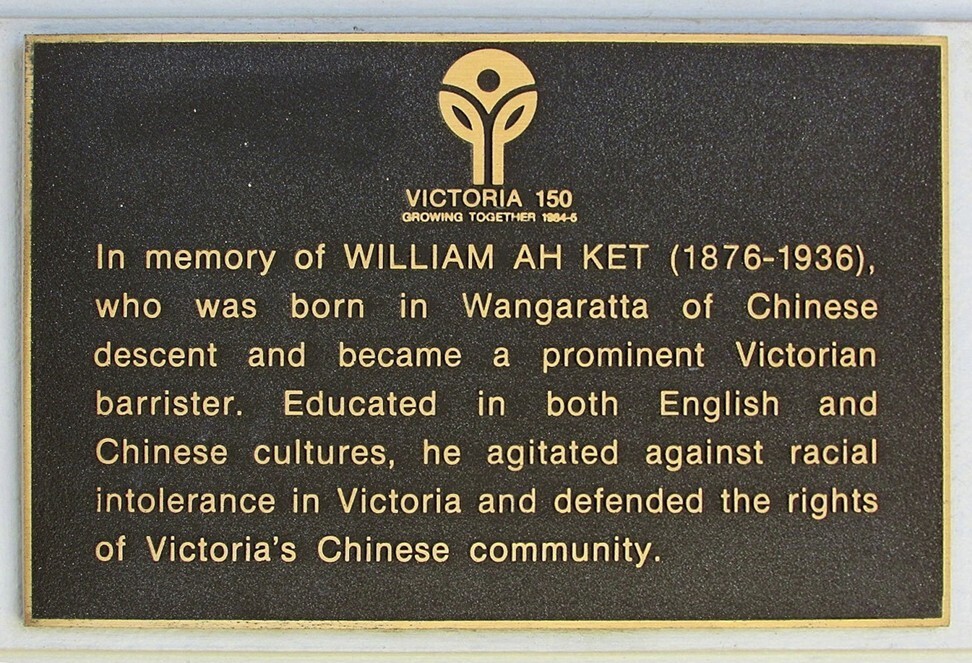

The first Chinese-Australian to join the Victorian Bar was born in June 1876, in a small town 200km (125 miles) northeast of Melbourne.

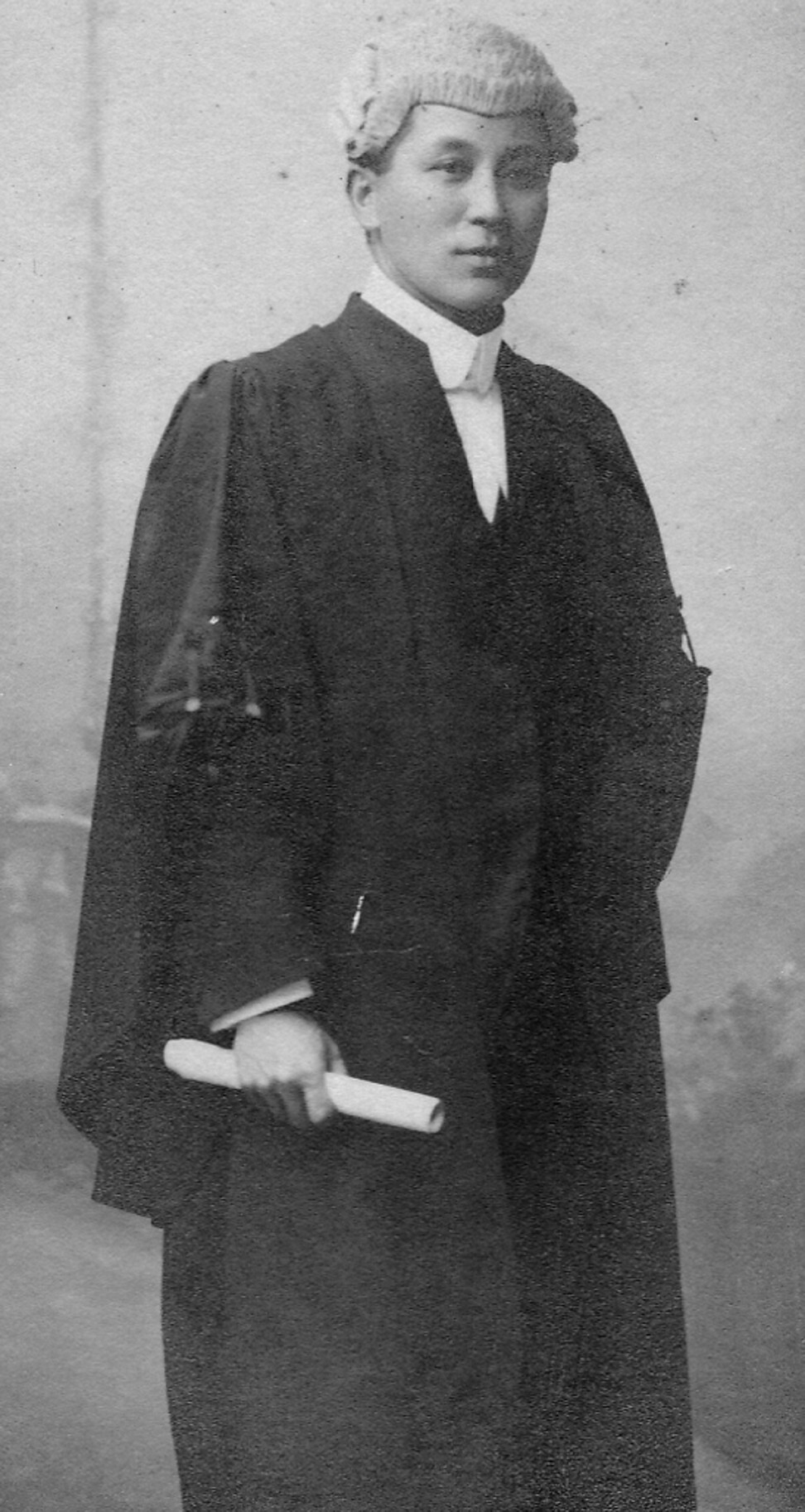

Admitted to the Bar to practise as a barrister and lawyer in 1903, William Ah Ket joined a conservative profession two years after the introduction of the White Australia policy, the notorious suite of laws designed to prevent non-Europeans from migrating to Australia.

While his name is little known in the wider Australian community, Ah Ket’s legacy has resurfaced over the last two decades among legal professionals, who remember him for his landmark victories in court and his battles against racist policies.

“I think his story is a very important one to tell, especially in the current climate, when it’s easy to be critical of the Chinese and to overlook how the Chinese are part of the fabric of Australian society,” says Andrew Godwin, a Melbourne University academic and an expert in Asian commercial law who spent 10 years working as a lawyer in Shanghai.

Born in the Victorian town of Wangaratta, Ah Ket was the only son of mother Hing Ung and father Mah Ket. His father was a tobacco farmer, opium seller and shopkeeper who migrated from southern China to Australia to join the gold rush in 1855.

Mah Ket was also a court interpreter in his spare time for his Chinese countrymen and a highly respected leader in the Wangaratta community.

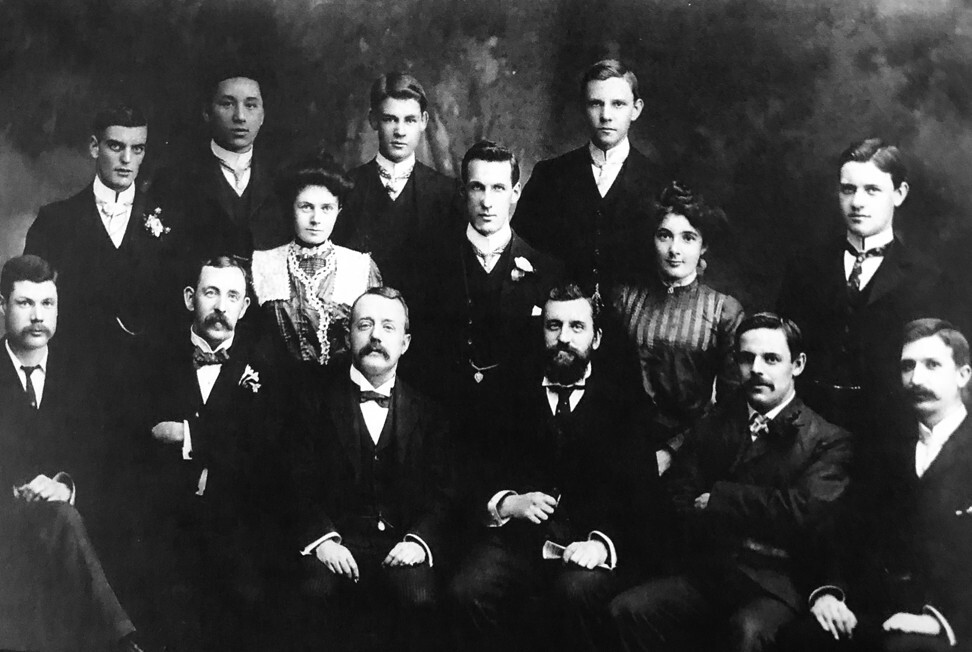

Ah Ket began interpreting both Cantonese and Mandarin when he was a teenager, and after graduating from high school in 1893 he went to the University of Melbourne to study law.

In 1904, he became the 88th barrister admitted to the Victorian Bar. Although 88 is a lucky number in Chinese culture, it was not a factor in his legal prowess. Two years earlier, he had won the Supreme Court Judge’s Prize while completing an articled clerkship with Messrs Maddock & Jamieson, which he finished the following year.

Highly regarded by his peers, Ah Ket appeared before the High Court of Australia at least 12 times between 1905 and 1928.

“He must have been a great optimist in terms of Australian society and what we could achieve, and I think it’s in that regard that his legacy lives on,” says Godwin.

Keen to fight against legislation that discriminated against people of Chinese origin, Ah Ket is remembered for his work on the case Ingham vs Hie Lee, which marked a turning point in eliminating an act that legalised discrimination against Chinese workers.

On the evening of May 31, 1912, a Chinese man found ironing a blue shirt in Hie Lee’s laundry in Carlton, Melbourne, was charged under the Victorian Factories and Shops Act 1905, which prohibited any after-hours work in a factory or workroom where a Chinese person was employed.

The man was later seen wearing the same blue shirt to court, meaning he owned it, and Ah Ket’s efforts saw the case dismissed with costs by the Victorian Supreme Court.

“In many ways it’s quite extraordinary when you think about the times in which he lived and how he did as well as he did,” says Godwin.

Despite Ah Ket’s legal nous, he still faced prejudice, often from his own clients. In the 1970 book The Measure of the Years by Australia’s longest-serving prime minister, Robert Menzies, he referred to his colleague and friend Ah Ket as “a phenomenon at the Victorian Bar” but that “a certain prejudice among clients against having a Chinese barrister to an extent limited his practice, though instructing solicitors thought very well of him”.

“William Ah Ket did not ever sit on the Bench, though he would have been a very competent judge,” Menzies wrote. “He was a sound lawyer and a good advocate. His bland Oriental features gave nothing away; his keen sense of fun was concealed behind an almost immovable mask … He was considerably senior to me but we were great friends.”

Each August since 2017, the William Ah Ket Scholarship committee has accepted applications for the most outstanding research paper on a topic dealing with equality, diversity, and the legal profession or the law from legal trainees, graduates, final year students and lawyers with less than five years of practise.

The annual scholarship, which awards A$6,000 (US$4,300) to the winner and two A$1,000 grants for notable submissions, was established by the Asian Australian Lawyers Association and sponsored by Ah Ket’s former firm, now called Maddocks.

The award took 11 years to bring to fruition, says association co-founder William Lye, who credits his wife, Cheri Ong, founder of the Asian Australian Foundation, for the idea.

Malaysian-born Lye was the second ethnic Chinese person to join the Victorian Bar, in 1988, 84 years after Ah Ket.

“For many people of colour, regardless of whether they are Asian or Chinese, I think it’s inspirational to hear the stories of people who look different,” Lye says. “People need to see that, so they know that all their efforts will not go to waste.

“When I became a barrister, there was no other person who looked like me. Who do I confide in or [who] consoles me?”

Lye says championing diversity is always important. “What is more important, that most people fail to recognise, is that there is an aspect of sponsorship,” he adds. “What I have seen is that those who have made it broke through the ceiling, if you can call it that, they then disappear from the scene.

“Being a barrister is a craft that takes a lifetime. There are no short cuts … Along that journey you need to have people to lead the way and show you the way. For those who have succeeded, there’s a duty or obligation to help the younger generation, to mentor them in a positive way.”

The William Ah Ket Scholarship has been cancelled for this year, after a state of disaster was declared in Victoria to address the coronavirus pandemic, but there are plans for a 2021 scholarship.

Although Melbourne has been put on pause, Godwin says plans to commemorate Ah Ket’s life are being planned for later in 2020, with a presentation on Ah Ket to be held at Melbourne Law School that may include participation from the Victorian Bar.

Blossom Ah Ket, William Ah Ket’s great-granddaughter, describes her forebear as someone who was a giant of his time.

“For me it’s been a really good lesson into learning more about my family history and the fact that my Chinese family has been here longer than my English family,” she says. “I think he’s relevant to me not just because he was Chinese and a brilliant lawyer, but also because his work really helped his community.

“I found out relatively recently that his first job was as an interpreter of Cantonese and Mandarin,” adds Blossom, a Spanish-English court interpreter who was involved in a recent project when Melbourne locked down nine public housing blocks after some tenants tested positive for Covid-19.

Besides the law, William Ah Ket had an interest in many spheres of Australian life. He was involved with the Chinese Empire Reform Association of 1904, set up to support the Guangxu emperor’s return to power, and the Anti-Opium League of Victoria.

He was a delegate to the first interstate Chinese convention, held in Melbourne in 1905, a co-founder and president of the first Australian-Chinese club, the Sino-Australian Association, and acting consul-general for China in 1913-14 and in 1917.

Reynah Tang, co-founder and inaugural president of the Asian Australian Lawyers Association and the first ethnic Chinese president of the Law Institute of Victoria, says Ah Ket’s legacy makes it clear that achieving diversity requires effort.

“I think what is important about his legacy is that often when you try and talk about cultural diversity in the legal profession, and particularly about Asian-Australians, you’re met with this response that you just have to give it time,” he says. “People say, in 10 or 20 years it’ll all be solved.”

Tang says Ah Ket’s story illustrates the broader question of how the ethnicity of the legal profession and the judiciary should reflect the communities they serve.

“We look back more than 103-ish years ago and we already have an Asian-Australian who was quite an impressive barrister and spent over 30 years at the Bar, and couldn’t become a senior counsel at the Bar or get an appointment to the judiciary,” he says.

From our archive