Review: Land Abounds, Ngununggula

Ngununggula (pronounced Nun-uhn-goola), in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, at first appears to be the most contradictory of contemporary art spaces. The reconfigured dairy is a part of Retford Park, the grand estate bequeathed by James Fairfax to the National Trust.

The gallery, designed by Brian Zulaikha, places the new so that it sits gracefully with the old.

The entrance pavilion shows Quandamooka artist Megan Cope who worked with the local Aboriginal community to create an installation to celebrate their language and culture.

Director Megan Monte aims to embed connections between land, place and people into all Ngununggula’s activities. These are not limited to art. People come for Yoga and Tai Chi classes, and stay for coffee and art. Children are welcome both as participants in Saturday art classes and to visit on school excursions.

Local artist Ben Quilty was involved in the considerable networking and fundraising to get a gallery of this scale built. One of his original motivations was realising his children had to travel to Canberra or Sydney to see art exhibitions.

The exhibition program ranges from a survey of the local artist John Olsen, to the intellectual and emotional challenge of the current exhibition, Land Abounds.

A place for new and old art

James Fairfax is rightly remembered as the visionary chair of John Fairfax & Sons, the man who presided over The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The National Times and the Australian Financial Review when they published some of the best journalism this country has seen.

In 2011, Fairfax commissioned a heritage assessment of Retford Park, originally built as the country estate of Samuel Hordern. After he had bought it in 1964, Fairfax had restored the house and landscaped the gardens, but paid no attention to the dairy.

For over 30 years local residents had been agitating for a regional gallery, a place to show new art, as well as old.

Local artist Ben Quilty may be best known for his art, but he has another talent – networking. He knows how connections between people work, and with a disarming smile, can convince people of the reasonable nature of his vision.

The National Trust was persuaded the old dairy and veterinary clinic, at risk of deterioration, was the ideal site for a functioning art gallery. The local Wingecarribee Shire Council and the state government were persuaded to join the partnership. The distinguished heritage architects Tonkin Zulaikha Greer undertook a feasibility study to show all was possible.Private donors, including the James Fairfax Foundation, completed the picture.

Read more: Friday essay: 10 photography exhibitions that defined Australia

Artists as outsiders

Two artist brothers: Abdul Abdullah and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, living on opposite sides of the country, have bounced their work against that of one of their most admired artists, Tracey Moffatt, in particular the movie montages she made in conjunction with Gary Hillberg.

Abdul-Rahman has described the exhibition as “an ongoing conversation between the practices of my brother and I, brought to bear on the enduring legacy of Tracey Moffatt.”

They see their work as being profoundly influenced by the way she elegantly confronts the big questions of race and cultural difference mainstream society prefers to ignore.

Abdul Abdullah has said, “I have felt that my entire practice was influenced by seeing her work Other at the 2011 Singapore Biennale.”

The brothers first met Moffatt in 2014, participating in her work Art Calls, and as Abdul Abdullah describes it, they “have been friends ever since”.

Visitors to the exhibition can see video conversations with the brothers, next to a screening of Moffatt’s Doomed (2007), reworking catastrophe.

The sense of unease is accelerated in Abdul-Rahman’s The Dogs, where a pack of black carved animals appear to race toward the viewer, teeth bared, their savagery emphasised by the glittering chandeliers that hang above them, telling the viewer to go away.

Although the Abdullah brothers are the seventh generation of their family to be Australians, their Muslim faith and names continue place them as perpetual outsiders.

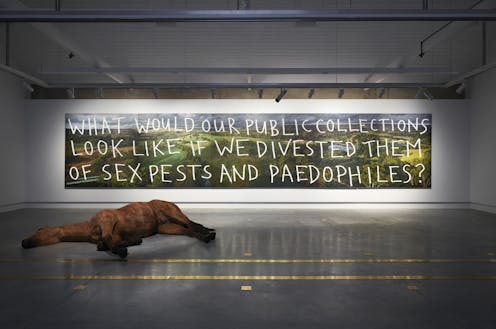

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s carved animals have a frightening reality. His Dead Horse lying on the hard gallery floor, evokes pity for its state. The artist sees its many possibilities:

A horse is many things; a trophy, a companion, a resource.

A dead horse is many things; a tragic failure, a half tonne of pet food, a senseless repetition.

The horse’s isolation is emphasised by being placed in front Abdul Abdullah’s epic work, Legacy assets, a ten metres long painted panorama of the pastoral ideal. This classic landscape of the Southern Highlands, fields and trees with a river running through it, is countered by the stark white printing of the artist’s message:

WHAT WOULD OUR PUBLIC COLLECTIONS LOOK LIKE IF WE DIVESTED THEM OF SEX PESTS AND PAEDOPHILES?

There is no comfort here. Abdullah has long been concerned that “the projection of genius on deeply flawed individuals was used to justify and obfuscate abhorrent behaviour”.

This is a painting to make us ask whether the aesthetic ends ever justify the means. Can the price of beauty be too high? Is the language of art a “language of entitlement”?

On the opposite wall Tracey Moffatt screens Other (2009), wittily mocking the exploitation of people of colour in popular American cinema.

The name Ngununggula, in the language of the local Gundungurra people, translates as “belonging”. It works.

Land Abounds is at Ngununggula until July 24.

Read more: In Abdul-Rahman Abdullah's Pretty Beach, a fever of stingrays becomes a meditation on suffering

Joanna Mendelssohn has received funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.