When Dave Davies is your uncle, it’s a fair shot you’ll have at least a passing interest in guitar. The Kinks guitarist’s nephew, Phil Palmer, has that and more.

Dating back to the early '70s, with his trusty Fender Nocaster – a gift from Uncle Dave – Palmer has played in dozens of sessions including appearances with Iggy Pop, Sheena Easton, Eric Clapton, Bryan Adams and Dire Straits, of whom he was an official member in 1992 and ’93.

Indeed, they call him ‘the Session Man,’ and Palmer holds the moniker so dear he’s named his autobiography after it: “I’ve had a long career,” he tells Guitar World. “And I was never one to think about it; I just went from one project to the next.

“Then the lockdown came, and it occurred to me I was sitting on my bum, so I might as well write about my career. And I’m glad I did it. It was fun researching myself, looking back on everything I've done, and then thinking about why I did it.”

Memoirs aside, the guitarist is also on the road with the Dire Straits Legacy tribute act. According to Palmer, it’s been a blast, but no new music will come out of it: “We’re just getting off on touring,” he says. “But I promise you that the reaction we get wherever we play is the same as when I was in the band. People love the songs.

“And they should – they’re pieces of genius. They’re brilliant and they’re great to play. So as long as they keep moving people we’ll keep delivering them. Honestly, I’m busier now than I’ve ever been. Being a session player is about getting away with it, and given how busy I am, I guess I’m still getting away with it!”

Your uncle is Dave Davies. Is that who influenced you to pick up the guitar?

“Yes. My uncles were in The Kinks, which was and still is a massive influence on me. But the guitar came about when I was five after I’d picked up a ukulele. And as my hands grew, I got into six-string acoustic and electric guitars.

“But Dave helped me a lot and supplied me with a few early instruments, including a Vox amp and a Fender Nocaster he'd picked up in America. He gave that guitar to me for my 18th birthday, and by the time I was 20, I knew what I wanted to do with my life.”

Can you recall your first session?

“It was with a young girl called Claire Hamill. She was from County Durham in North England. She was signed to Ray Davies’ Konk label and had a few hits. I was very young and just noodling around, and when Claire came into the studio, I didn’t know she was there, and she heard me playing and said, ‘I need help on my next tune. Would you like to play on it?’ And that was my first session.”

As a session player, how do you approach rhythm and lead playing – especially given that you need to be a chameleon?

“It’s a matter of being invisible. During sessions, you learn some of everything from being thrown into the deep end. So, you either sink or swim. You quickly learn when to play, when not to, and how to read what people need.

“It becomes a fascinating psychological journey, since you’re walking into a room filled with strangers. But if you’re good and get away with it, you’ll do more sessions and get good at it. So I approach it by knowing when to be invisible and when to shine.”

You mentioned the Nocaster that Dave gave you. Did that become your go-to guitar?

“I did use it often. But I used to carry a cross-section of stuff. I’d always have an acoustic, a nylon-string, and a couple of electrics. I’d also have a Vox AC30 and a few pedals, too.

“I liked to have a compression and chorus pedal, but the latter kinda went out of fashion in the ‘70s, so I stopped using it. I was never a big pedals guy – I’d rather drive the amp using the valves and get some crunch from there rather than pedals.”

Tell me about your contributions to Iggy Pop’s The Idiot.

“I was home one evening, and at around four o’clock in the morning I got a call from David Bowie, who was in Berlin at the time. He said they needed a guitar player for Iggy’s album and asked if I’d come over.

“I threw the Nocaster on my back and, a few days later, I was in the studio. It was a strange session – there was a lot of energy between David and Iggy. They were winding each other up and finding exciting things. I found myself stuck in the middle, but it was very interesting.

I said, ‘Any clue about the key?’ David Bowie said, ‘Don’t worry about the key, just the rhythm. Be the music…’

“The first track we did was Nightclubbing. David’s direction was: ‘Imagine you’re walking down a busy street in London with music coming out of both sides, and as you’re walking down, you hear the music coming out of nightclub doors.’

“So, I said, ‘Right. Any clue about the key?’ And David said, ‘Don’t worry about the key, just the rhythm. Be the music that you’re hearing coming out those doors.’”

You used the Nocaster, but what amp did you plug into?

“It was vague. I just stood inside the studio with a Marshall amp and a wah pedal that belonged to Thin Lizzy – who were also in the studio – and gave it a shot. Another weird thing was we’d be recording all night from about 11pm to 8 or 9 in the morning. But a lot of cool gear was around; I just plugged in and made a racket that seemed to fit the bill.”

Fast-forward to the late ‘80s, and you’re working with Eric Clapton. How did you meet him?

“I had been working with a talented Irish singer called Paul Brady; we did a few big albums and tours through Europe. The first time I met Eric was through Paul, while playing in a small club called The Mean Fiddler. I’ll never forget it – I looked up and Eric was in the crowd. That was unexpected!

“I ran into him down the line while on holiday in the West Indies; we were both on the beach, and he asked me to come down and play on his Journeyman record, which I did.

“I loved working with Eric because he gave me space to play. Unlike other sessions I’d been on, he wanted me to bring something new to the table and contribute.”

What lessons did you learn while touring with Eric?

“An example of the lessons I learned can be heard on our Royal Albert Hall vinyl recordings. He reminded me to be at home on stage and never be nervous – Eric never was. He loved big events, and he always enjoyed the evening. So, a big lesson for me was always remembering to have that mindset and do the same.”

Before joining Dire Straits, you had a chance to play on Eric’s Unplugged record, but had to turn it down. Is that right?

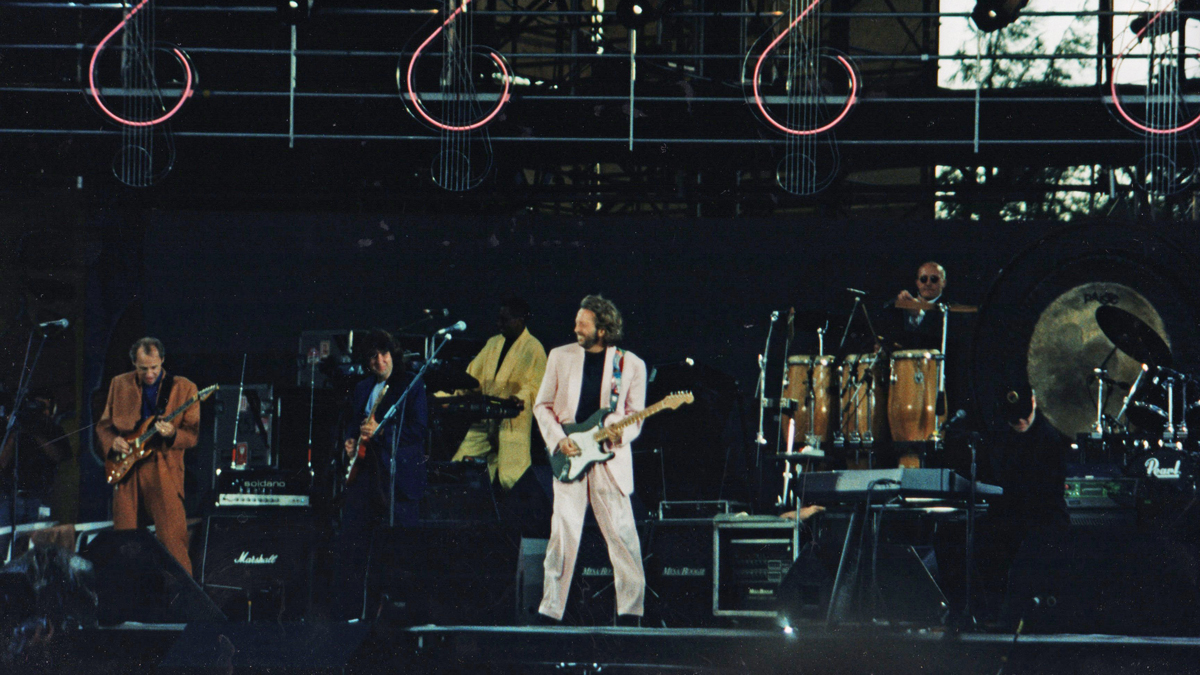

“I was still working with Eric, and we did a big outdoor show in Knebworth. During that gig, Eric and Mark Knopfler decided to amalgamate the two bands, and we did some of Eric’s songs and some of Dire Straits’ songs. I got on well with those guys, and things evolved to the point that I ended up joining them.

Eric Clapton reminded me to be at home on stage and never be nervous – Eric never was. He loved big events, and he always enjoyed the evening

“But the catalyst was that Eric had a major disaster in his life when he lost his son in New York, who fell out of a window and sadly died. We all went to the funeral, and just after, Eric’s manager said, ‘Guys, if anything comes up you should take it, as Eric won’t be doing anything.’

“Soon after, I negotiated a deal with Mark and signed a contract with Dire Straits. But literally the day after, Eric called me, saying, ‘Listen, I’m not going to sit around on my ass. I want to make an Unplugged album. Can you do it?’ I had to turn it down. It was terrible.”

Mark Knopfler is undoubtedly different from Eric. Was there a period of adjustment for you?

“Strangely, one of the reasons I got the gig with Dire Straits is that I came from the same school as Mark. I played fingerstyle and had the same country influences, and that’s probably why I fit so well.

“Up to that point, the guitarists that Mark had in the band didn’t do much – I think he had me come on because he wanted to be challenged. He wanted me to play a lot of what he played so he could easily explore new avenues, other licks and new ideas.

“I had to learn his very strange picking technique, where his right hand, almost like a banjo picker, does these odd things. So we got together, I nailed it, and off we went. Mark is so inspirational, and he loves to experiment. It was amazing to play alongside him for those two years.”

I had to learn Mark Knopfler’s very strange picking technique… So we got together, I nailed it, and off we went

These days, you're on the road with the Dire Straits Legacy tribute. What's the latest?

“Over the last 10 years we’ve been keeping the Dire Straits thing alive. It happened by accident. We were brought together for a charity gig in Italy – and to our surprise, 10,000 people showed up. There was no promotion; it just happened.

“So we said, ‘Wait a minute, this has some legs. Why don’t we follow it and see it through?’ And 10 years later we’re preparing to go to Germany, Shanghai, Australia, and New Zealand. We love doing it, and we’re looking forward to more.”

- Palmer’s book, Session Man, is out now.