There’s more than one way to uncover what a planet is made of.

Scientists suspect that two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star may be mostly water, according to a recent study using data from two NASA telescopes. But before you start picturing Kevin Costner in Water World or even the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, pause: These two exoplanets are far stranger than that.

What’s new – Finding evidence of water on distant planets is a longstanding goal for astronomers and astrobiologists. The study, led by University of Montreal astronomer Caroline Piaulet and her colleagues and published today in the journal Nature Astronomy, suggests that two exoplanets don’t just have water covering their surfaces, the entirety of their being is likely water.

Kepler-198c and 198d are a pair of exoplanets orbiting a small, dim star called Kepler 198, about 218 light-years from Earth. The two planets are practically twins; they’re both about 3 times as large as Earth, with twice our planet’s mass. In other words, these twin worlds are much less dense than our rocky homeworld, and that’s why Piaulet and her colleagues surmise they’re mostly water.

Using data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and its now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope (RIP), Piaulet and her colleagues measured the radius of both planets as they passed in front of their star. Based on their orbits and the way Kepler 198 wobbled slightly from the planets’ gravitational pull, Piaulet and her colleagues could also calculate each planet’s mass. From there, a quick division problem revealed how dense the planets were — and the answer was surprising.

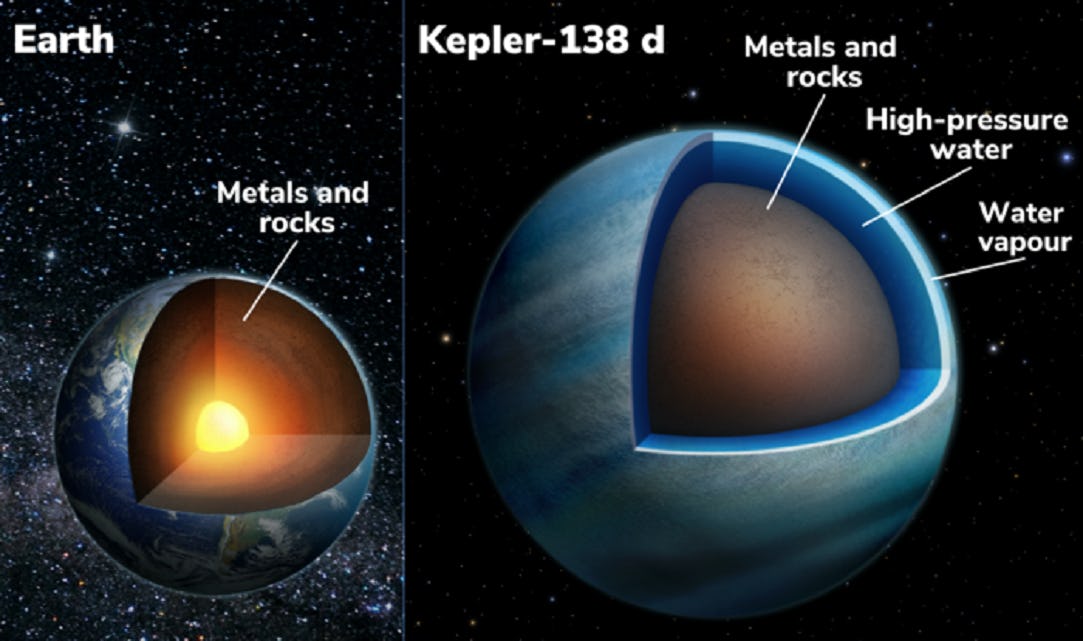

Both Kepler-198c and 198d are much less dense than you’d expect from a planet like Earth, which is mostly metal and rock (sorry, pop fans). But they were also too dense to be smaller versions of Jupiter and Saturn, which are made of mostly hydrogen and helium. Instead, both planets were about the density you’d expect from something made mostly of water around a rocky core. To be specific, water makes up slightly more than half Kepler-198d’s volume and about 11 percent of its mass.

“Imagine larger versions of Europa or Enceladus, the water-rich moons of Jupiter and Saturn, but brought much closer to their star,” explains Piaulet in a statement. Kepler-138c and 138d orbit so close to their star that the temperature at their surfaces is above the boiling point of water. Instead of globe-spanning oceans beneath a crust of ice, the twin water worlds probably have deep, steamy atmospheres of mostly water vapor. Beneath all that steam, Piaulet and her colleagues say it’s possible there could be a layer of liquid water, or something called a supercritical fluid: a weird phase that behaves a little like a liquid and a little like a gas and only forms at very high pressures.

These worlds sound pretty weird, but recent studies suggest that in the grand scheme of things, they may actually be the norm.

Here’s The Background – Of the thousands of exoplanets astronomers have found orbiting other stars, many are so-called super-Earths: planets about one and a half to two times as large as our world. Astronomers have long assumed that most of them are made of a mix of rock and iron similar to Earth, just on a larger scale, hence the name. Some super-Earths might have atmospheres and liquid oceans or lakes on their surfaces, but they’re definitely the sort of place where you could stand on solid ground. Or so astronomers thought.

A study published in September 2022 suggested that a surprising number of super-Earths might actually be water worlds, made up mostly of water in some form — ice, liquid, or steam. Like Piaulet and her colleagues’ conclusions about Kepler-138c and 183d, astronomers Rafael Luque (of the University of Chicago) and Enric Pallé (of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands) based their conclusions on the density of the 34 exoplanets in their study. Some turned out to be rocky and Earth-like, while others turned out to be puffy balls of gas, but a surprising number of the planets looked like mostly water over a core of rock and metal.

Another recent study found a potential water world orbiting the star TOI-1452b. So far, however, astronomers are drawing conclusions about these planets based on their density — not on actually measuring what’s in their atmospheres.

What This Means For Alien Life – Water is a requirement for life as we know it, but if all the water on a planet is frozen or boiling, even a water world may not actually be habitable. Kepler-138c and 138d are outside their star’s habitable zone — the region around a star where temperatures are right for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. In this case, the twin water worlds are too close to their star, so any water at their surfaces should have boiled into steam.

But the icy moons in our own Solar System have shown us that the habitable zone is more like a guideline than a rule. Tidal heating on Europa and Enceladus is enough to keep oceans of liquid water churning beneath the ice. Kepler-138c and 138d have the opposite problem — it’s too hot — but if their steamy atmospheres are dense enough and deep enough, then the pressure at their bases could be intense enough to keep some water in liquid form. Higher pressure increases the temperature at which water boils; the reverse is also true, which is why Mars’ thin atmosphere is bad for keeping liquid water on its surface.

That’s pure speculation for now, based on the information available so far. What scientists need, of course, is more data.

What’s Next – Kepler-138c and 138d, along with TOI-1552b, are perfect exoplanet targets for NASA’s James Webb Telescope. They transit their stars (meaning that from our point of view, their orbits pass “in front of” the star, so the planet is silhouetted and easy to see). And they orbit very close to their small, dim red dwarf stars, so they’ll block relatively more light when they transit, making it easier for observatories like the Webb to measure their spectra, or the light absorbed and emitted by different chemicals in the atmosphere.

That could tell us whether there’s actually water vapor in these worlds’ atmospheres and, if so, how strong its signature is.

And other water worlds could be out there, just waiting to be found, either by density measurements or by measuring the spectra of their atmospheres.

“As our instruments and techniques become sensitive enough to find and study planets that are farther from their stars, we might start finding a lot more water worlds like Kepler 138c and d,” says study co-author Björn Benneke in a statement.