As the Beijing Winter Olympics get underway, all eyes are on China. There has been lots of coverage about China’s chilly relationship in the west and its persecution of the Uighur and other minorities, but there is also much to be said about the Chinese economy.

China’s great rise over the past several decades has been the great economic success of our times, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and giving the global economy wheels in the years after the financial crisis of 2007-09.

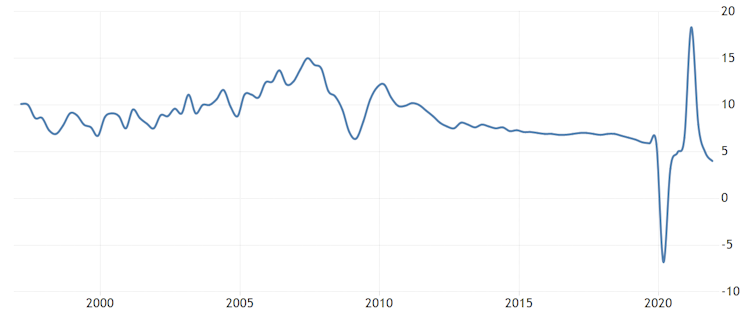

Over the past decade, however, the miracle became a bit more ordinary as growth gradually slowed. China found it difficult to keep increasing exports at the same pace year after year, particularly in the face of weaker international demand for its products – not least because of the trade war with the US. Other issues have included an ageing population and the fact that growth had become increasingly dependent on debt, which wasn’t sustainable.

China’s economic growth 1997-2021

China did seem to have weathered the pandemic better than many major economies, having contained the virus so aggressively. Yet the picture has since deteriorated as renewed domestic COVID outbreaks, including the new omicron variant, have caused fresh economic disruption.

Omicron’s effect on other major economies is not good news for Chinese exports either. Neither is the resurgence of inflation in many countries, which has prompted the US Federal Reserve and other central banks to threaten higher interest rates and an end to creating money via quantitative easing. This is likely to further dampen demand for Chinese goods.

China’s debt has also become an even bigger issue. Leading property developer Evergrande’s financial difficulties in 2021 made headlines, but excessive debt is rife throughout the property sector and beyond. If the bubble bursts, it could lead to a prolonged downturn that significantly damages the wider economy.

The government has been pressuring major companies to reduce their debts, while also restricting borrowing in the property sector and cracking down on informal lending across the country. It also sent a warning to excess borrowers through its willingness to let Evergrande default.

Weaker exports and reducing debt mean that China is heading for a slowdown: the World Bank projects that its economic growth will be just over 5% in 2022, compared to 8% in 2021.

China’s challenges

More broadly, China’s traditional growth model based on exports, infrastructure and real estate investment looks like it has run its course. The nation is facing a difficult rebalancing act as it aims to transition to relying much more on Chinese households consuming goods and services, while also having to move to a much less carbon-intensive economy.

Unfortunately for the ruling Communist Party, the best way to achieve this rebalancing is arguably to implement reforms that would limit the govermnent’s influence in Chinese life. For example, the World Bank thinks China needs to make it easier for companies to fail and to allow more private competition in sectors like education and healthcare as a way of driving up productivity. It also recommends enabling workers to move around the country by abolishing the hukou registration system in cities, since this system stipulates where someone is permanently resident.

Some World Bank recommendations do involve more government intervention, such as making the tax system more progressive to encourage consumers to spend more, and raising government spending on health and education so that people don’t need to save so much. Generally speaking, however, more liberalisation is the order of the day – and looks like the right way forward from my point of view.

Yet China has become more interventionist in the Xi era, cracking down on everything from tech billionaires to the number of hours that children can play video games each day. Meanwhile, China’s zero-COVID strategy has involved tightly sealed borders, swift citywide lockdowns and mass testing.

China adopted this strategy partly out of fear that its poor healthcare system could be completely overwhelmed by COVID, and more recently as a way of ensuring that the Winter Olympics proceed smoothly. Yet such is the climate in China that some commentators fear that it will not open up again, that the health crisis is turning into a political crisis of more committed isolation.

China therefore finds itself at a crossroads. On the one hand, it wants a greater role in the global economy, as can be seen through its Belt and Road Initiative to drive infrastructure development around the world in exchange for closer ties with Beijing.

But there is a contradiction between continuing to engage with global trade and the Chinese government’s instinct towards technological self-sufficiency and homegrown innovation. Trade liberalisation also requires, for example, opening up the banking sector to foreign lenders to make it more efficient. Yet that is a long way from Beijing’s interventionist approach. Indeed, the fact that the banks, which are partly owned by the state, were given mandates to lend to state-owned companies with poor financial status was the cause of many the debt problems in the first place.

Unfortunately, the indications are that China is more likely to move towards greater isolationism from the west. This might mean restricting people visiting the country and concentrating more on domestic consumption than global trade. We might see it further tacking away from globalisation via trade wars, as well as imposing greater capital controls to make it harder for money to get in and out of the country. Obviously, China is partly acting out of provocation from the west, but its overall policy shift has been to a large extent homegrown.

As with the winter Olympics, where China is trying to keep the athletes separate from its people, the nation is also behaving in a similar way with regard to the rest of the world. What should be a celebration of international cooperation is happening at a time when the exact opposite is taking place.

Kate Phylaktis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.