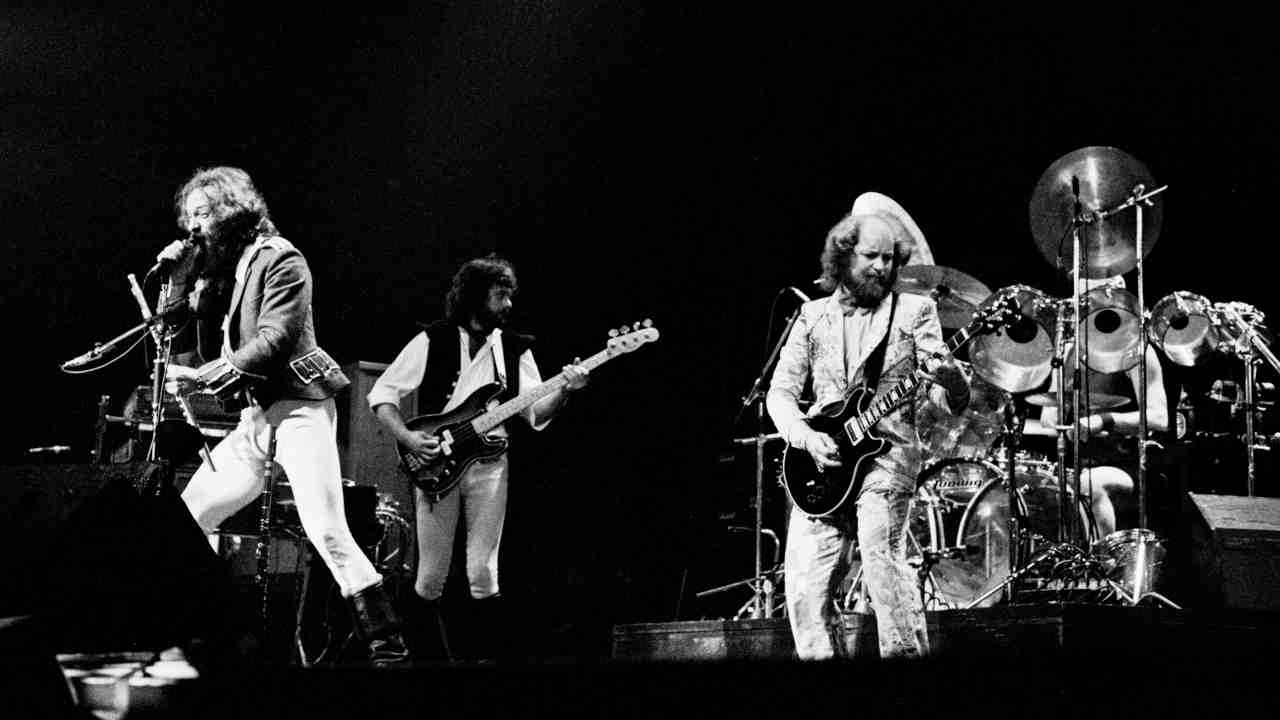

It’s not quite Beatlemania, but the parallels are obvious. Eleven years after the Fab Four had made history at Shea Stadium, another British band are on stage at the famous baseball mecca in Queens, home to the New York Mets. It’s a damp Friday night in July 1976, but the crowd is in high spirits, launching firecrackers into the rainy sky. Under an enormous canopy upheld by two cranes, Jethro Tull are playing in front of 50,000 fans, flanked by giant screens relaying the action via their own unique video system, Tull-A-Vision.

Support acts Rory Gallagher and Robin Trower have done their best to warm up the audience, but Tull – led by the charismatic Ian Anderson – are the reason why everyone’s here. Anderson himself isn’t having a particularly great time of it. The noise of rush-hour jets at LaGuardia Airport, just two miles away, is making it hard for the band to hear themselves play. What’s more, some joker had thrown a pint of urine over the frontman, from a great height, as he made his entrance from the tunnel. So now he’s covered in piss. Despite these irritations, however, the significance of the moment isn’t lost on him as he looks out into an endless sea of faces: Jethro Tull have become a massive stadium band.

This is just a relatively modest turnout compared to their West Coast visit three weeks later. 80,000 people will descend on LA’s Memorial Coliseum that night in August, confirming Tull’s status as superstars of Led Zeppelin-style proportions. Back home, Melody Maker’s recent headline – “Jethro: Now The World’s Biggest Band?” – didn’t seem quite so fanciful as it first appeared.

So just how did a weirdo bunch of Limeys manage to crack America? The mainstream US market was notoriously difficult for foreign artists to penetrate in the ‘70s. Many bands who sold bucketloads back home couldn’t manage it Stateside – T.Rex, Slade, The Kinks and Status Quo included. Even David Bowie didn’t hit megstardom until the ‘80s. All of which made Jethro Tull an anomaly. Their strange hybrid of folk, jazz and prog was an unlikely hit in a land where the big stage was traditionally ruled by barnstorming rock‘n’roll.

Yet it was no fluke. Jethro Tull made great records that succeeded in translation. They were also a band that instinctively grasped the value of rock as high theatre, sending themselves up – along with the whole ludicrous business – in a manner as flashy as it was knowingly preposterous. Above all though, they had a plan. Repetition, they decided, was the only way to conquer America.

Jethro Tull hardly stayed away. As a measure of the band’s devotion to the task, they’d already toured the States 11 times by the end of 1971, despite being barely three years into their recording career.

Their first trek across the ocean had been in late January 1969, just ahead of the US release of debut LP, This Was. They were supporting Blood, Sweat & Tears at the Fillmore East in New York City, under the auspices of promoter Bill Graham. “He was a guy without whom probably Jethro Tull would never have gotten started,” Anderson told Smashing Interviews magazine in 2017. “We were there for 12 or 13 weeks on that first tour. A lot of the time we were sitting on our hands in very cheap accommodations, hoping there’d be somewhere for us to play tomorrow night.”

Tull found themselves doing short residencies at venues like Boston’s Tea Party (another Bill Graham stronghold) and the Stone Balloon in New Haven, Connecticut, playing to less than 30 people per night. During their downtime at the Stone Balloon, Anderson took the opportunity to write a new song.

“I remember being in a Holiday Inn somewhere,” he told Prog in 2015. “I was in the lobby of the hotel and our manager Terry Ellis said ‘Could you rustle up a three-minute hit single? Something we can release in the UK while we’re away, to keep the pot boiling back home’.” The resultant song, Living In The Past, made the top three in Britain on release in April ’69.

It was a different approach in the States. Still unsure of Tull’s commercial viability, Reprise chose to hold back Living In The Past. “Our American label didn’t want to release it in the USA because people wouldn’t get it and it was too complicated,” recalled Anderson. “People couldn’t tap their feet to it because it was in 5/4…I’m rather glad they didn’t because we needed more time to evolve.”

Allowing Tull to gradually develop an audience in the US was a crucial decision. This Was made its mark immediately in the UK, reaching the Top 10, whereas it hardly made a dent on the Billboard album charts. By the time Stand Up was issued as a follow-up in September ’69, the band had been gigging around the States with Led Zeppelin and Creedence Clearwater Revival.

With the album already at number one back home, Tull’s reputation was growing further afield too. Elvis Presley even invited them to join him backstage after a show in Las Vegas. Having sat through Presley’s less-than-great gig that night, Anderson thought it best to politely decline the offer.

“He was slurring his words, he didn’t know where he was,” the Tull singer explained later. “It just wasn’t the way to see Elvis.”

Stand Up made Tull a more confident live unit. “We had some new material to play,” said Anderson, “and it was an opportunity to get noticed in some other markets in the USA other than just the obvious major cities. So we expanded our position.” It’s the kind of statement that you might associate with a high-powered strategist in a company boardroom rather than a rock singer, but it’s a telling example of Anderson’s business savvy.

The album was their first to breach the Billboard Top 20. Tull now found themselves headlining at the Fillmore West in San Francisco, supported by the MC5, and filling places like the Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica. Released in the US in May 1970, the more riff-oriented Benefit seemed perfectly primed for American audiences too. The band reached an early peak that spring, at a sold-out Long Beach Arena in California, where they packed in around 15,000 people.

As the year drew to a close, Benefit was certified gold in the US. Tull’s appeal was all too evident. Anderson endeared himself to American audiences as the latest in a steady chorus line of great British eccentrics - part-jester, part-shaman, a wild-eyed piper with mad hair, flailing arms and hobo coat.

“Jethro Tull is the best rock group to come along since The Who,” gushed The Detroit Free Press. “The Who is good to use in comparison because of their theatrics. The scene-stealer is Ian Anderson.” The New York Times called him a “showpiece”, noting that “he dresses like a Dickens character and leaps about the stage like a man standing barefoot on a hotplate. While playing flute he stands on one foot like a stork, or else he seems to be shinnying up the mike stand.”

Impressed the visual exuberance of the entire band, Creem magazine was quick to declare: “Live rock as theatre has been standard since Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard first attacked a piano, but no-one has carried it as far as Anderson without resorting to props.”

Speaking to Circus magazine in 1970, in a hotel room high above the Sunset Strip, Anderson attempted to make sense of Tull’s burgeoning popularity: “We never went down like Led Zeppelin. We didn’t come to this country and take it by storm…With us it was a steady kind of climbing up, it’s a pleasant sort of thing.”

Whether the band had actually anticipated it or not, Tull’s ascent was about to quicken. 1971’s Aqualung - Anderson’s treatise on the broken trinity of God, man and organised religion – was an artistic and commercial triumph, striking a masterful balance of acoustic pieces and stadium-heavy rockers. It would eventually shift over seven million copies at home and abroad, becoming their first album to make the Billboard top ten.

In another echo of The Beatles, its US success even survived a backlash down South. “Aqualung got its share of bashings, particularly in the Southern States of America, where it was burned,” Anderson said in 2009. “It created a fair amount of localised anger amongst those ultra-conservative Baptist types in the States. But it blew over fairly quickly.”

Indeed, Tull’s pulling power was enough to sell out Madison Square Garden three weeks in advance. In October 1971 – the first of 18 visits to the Garden over the next few years – they played before an audience of 23,000. The following summer saw the band hit the top spot in the US for the first time, with their satirical concept piece, Thick As A Brick. Crucially, it was their first release to perform better in America than in the UK, where it stalled at No.5.

“I thought it might be a step too far for an American audience, but Monty Python had become a cult phenomenon there and Saturday Night Live and other things were starting to come along,” Anderson told Classic Rock in 2011. “So I think Thick As A Brick arrived there just at the right time. It went fairly quickly to the top of the Billboard charts and did very well. It’s Jethro Tull’s second biggest-selling album in America.”

The band’s commercial status was compounded by a double-LP compilation, Living In The Past, issued later in 1972. It was a release tailored for the American market, with one side devoted to a live show from New York’s Carnegie Hall. Chrysalis, now running Tull’s US affairs, finally saw fit to issue the title track as a standalone single. By January ’73 the song had become their first Top 20 hit Stateside.

The pattern had been set for the rest of the decade. As Tull’s popularity back home started to wane in slow increments, the US held steady. “America is consistent for us but here it’s trailed off as far as most people are concerned, in that we are not talked about so much,” Anderson told Melody Maker during a stopover in the UK. “In the final analysis, we do all right. We were too fast coming up in England.”

Despite mixed reviews, A Passion Play - another conceptual monster – gave the group their second consecutive chart-topper on Billboard. Anderson responded to the harsher critics of the music press with Only Solitaire, a caustic effort from 1974’s War Child. The album fell away quickly in the UK, but did smart business in America, buoyed by the inclusion of another major chart hit, the breezily direct Bungle In The Jungle.

Minstrel In The Gallery, released in September 1975, followed suit, going gold in the States but losing traction in Britain. It was a year in which the band sold out five dates at the 20,000-seater Los Angeles Forum. Tull fever was so intense that, on opening night, Anderson ordered his bandmates to stop playing due to the crowd making an unholy din. Melody Maker observed that “Ian Anderson had only to raise an eyebrow to bring the first ten rows to their feet.”

These were heady days. The addition of Tull-A-Vision – “Large Multi-Sided Video Screen Projection In Colour For Close-Up Viewing From All Seats!” screamed the gig posters in an age when such technology was still novel – only boosted the live experience. Even the relative failure of 1976’s Too Old To Rock‘n’Roll: Too Young To Die! didn’t dampen the party.

The idea for the album had occurred to Anderson during a turbulent flight between gigs in the US. “I hate flying anyway, but this was a really bad flight and I was convinced we were all gonna drop out of the sky,” he told Rolling Stone. “Just the words came into my head: ‘I’m too old to rock and roll, but I’m too young to die.’” A concept LP about an ageing greaser who refuses to bow to current trends, it could be taken as an allegory of Tull’s own bloody-minded attitude.

This singular approach couldn’t have been better illustrated than their next effort, Songs From The Wood. Released a week before The Damned’s first long-player, in February 1977, the album was a playfully bucolic take on British folk mythology and legend. But what seemed on the surface like a hopelessly contrary move in the era of punk, disco and AOR – and in a year when the airwaves were ruled by The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, Meat Loaf and ELO – instead proved a huge success, both at home and abroad. Songs From The Wood quickly went gold in the US and returned the band to the Billboard top ten.

The same went for its follow-up. On the surface, 1978’s Heavy Horses couldn’t have been less suited to the American market. Dedicated to the “indigenous working ponies and horses of Great Britain”, adorned with a photo of Anderson leading two Shire horses across a field, the album was an extended hymn to the value of homegrown traditions and the perils of consumerism.

Nevertheless, the US still happily lapped it up. It proved another big international hit. When Tull fetched up in New York in October that year, for another sell-out show at Madison Square Garden, it was beamed live via satellite on BBC’s Old Grey Whistle Test. In doing so, they became the first band to appear on a live simultaneous TV broadcast from America.

They continued to pack out arenas throughout 1979, culminating in a huge UNICEF benefit at Santa Monica’s Civic Auditorium in November. Broadcast live by radio station KMET-FM, the show found Tull promoting their latest effort, the eco-themed Stormwatch. The album may have been another sizeable hit, but it also effectively signalled the end of the band’s extraordinary run of success since Stand Up, ten years earlier.

This didn’t have anything to do with shifts in popularity. Rather, it was the result of seismic changes within the band itself. As the Stormwatch tour drew to a close in early 1980, drummer Barrie Barlow, piano player John Evan and multi-instrumentalist Dee Palmer all quit. A major catalyst was the tragic demise of bassist John Glascock, who had died of congenital heart failure while Tull were away on tour.

“The ‘70s were very productive for us in terms of people and musicians together,” Anderson reflected in 2013. “But elements within the band had been growing apart. It was just a sense of people heading in different directions. I got to the point where I thought: ‘OK, probably best to put this on ice for a time and do something different.’

Tull would eventually regroup and plot a more synth-based course through the early ‘80s. They would revive their commercial fortunes as the decade wore on (culminating in 1987’s Grammy-winning Crest Of A Knave), but they were never likely to repeat the successes of the ‘70s, when they held their own alongside Led Zeppelin, Queen, Elton John and The Rolling Stones as one of our most prized American exports.

Anderson was always at a loss to fully account for Jethro Tull’s massive popularity in the US. But he did have some idea. “I think the Americans kind of liked it because we didn’t look like we cared too much,” he suggested to Prog in 2017. “Some other British artists cared too much about being loved. When you do that, the chances are audiences don’t because they see through the mask…I think those of us who appeared to not give a damn were the ones who made the impression.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Jethro Tull