Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images of deceased people.

Amy Elwood, a Wangkumara/Adnyamathanha Elder and cultural repository of knowledge and grandmother to one of us (Lorina Barker), has inspired an array of creative works about her experience of removal from Country.

In 1938, 130 Aboriginal people including Amy’s family and other Wangkumara families were forcibly removed from Country at Tibooburra to the Brewarrina Aboriginal Station – the old mission.

The community was transported 500 kilometres east to the Baaka Barwon rivers on the back of three gubbie (government) trucks.

In 2006, Lorina had a yarn with her grandmother about her life experiences and memories. This was transformed into a poem titled An Ode to My Grandmother, a short film called Tibooburra: My Grandmother’s Country and touring multimedia exhibition named Looking Through Windows.

That yarn also inspired an immersive theatre performance Trucked Off, and the song An Ode to My Grandmother.

Read more: Friday essay: histories written in the land - a journey through Adnyamathanha Yarta

Learning from Elders

Oral history is the recorded account of a person’s memories of the past for historical and research purposes. Indigenous oral history is more than a methodology. It is living history, practised for thousands of millennia, intrinsically woven into Aboriginal people’s way of life and culture.

As Aboriginal people, we live it every day: it is a part of who we are, where we come from and who we are related to. It also determines our interconnected relationship and responsibilities to our lands, rivers, seas, skies and to all living and inanimate things in both the natural and spiritual worlds.

In these works, Amy Elwood is able to share her memories and stories and those of her family.

On the mission, life was harsh and regulated. The Wangkumara were not able to speak their language or practice their Culture; Elders worried for Country and many died of broken hearts.

In each development of the story, artists and musicians had to go through a process of decolonising themselves to work in an Aboriginal cultural framework. We were invited by Wangkumara Elders Gwen Barker, Rick Elwood, Rebecca McKellar and Louise Elwood into culturally creative spaces online and on Country where knowledge was transferred into new forms.

With each successive workshop and performance, we learnt more from the Elders through yarning and storytelling. The creative process from the poem to the final performance was developed over many years.

Retelling history

An immersive theatre work, Trucked Off started with the poem. In immersive theatre, the audience are not passive bystanders, they are part of the story.

In Trucked Off, the audience follow the Tibooburra families, walking in their shoes, reliving the journey from Tibooburra to Brewarrina in the far northwest of New South Wales.

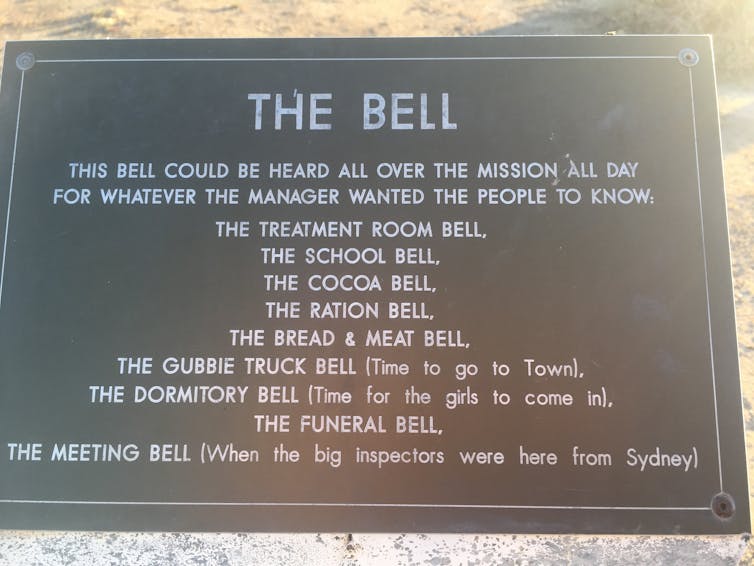

On arrival at the mission, the old Brewarrina Station, the audience are told by the mission manager and staff how their lives will be ruled by the ringing of a bell. The number of rings indicates how they will respond: if they are required to assemble for work, obtain rations, or, for children, go to school or to see the nurse for “treatments”.

The penalties are harsh for noncompliance.

Wangkumara Elders, including Lorina’s mother Aunty Gwen Barker, participate as actors in Trucked Off, taking ownership of their story and retelling their history.

The script is dynamic, incorporating themes of grief, loss and trauma that reverberate through the generations, reflecting the continuing impact of colonisation.

This is a theatre of “truth-telling”, embodied and experiential, increasing people’s understanding and memory of this living history.

Stories in song

Another work inspired by the poem was an operatic song. In the Western tradition, the composer has the final say over the music but this process required a new way of working that involved Community and the Wangkumara Elders.

The process ensured cultural protocols were observed and permissions sought to tell the story and to find the correct sound. Wangkumara Elders were able to give us detailed insight into the story and the emotion behind the poem.

The musical sections were mapped out and the Elders wanted the song to have an uplifting ending. This demonstrated the courage and resilience of the people, their connection to Country and to the Mura tracks (Songlines), even after removal. The song ends with a triumphant fanfare and the lyrics “Country knows you”.

While the poem is in English, the Elders added Wangkumara words into the song, including the word Ngamadja, which means “mother”. Wiradjuri soprano Georgina Hall discussed with Elders the many meanings of the words and the exact way to pronounce them while recording the song.

Language and the story of removal finds a new home in classical music and song.

The use of oral histories and archival materials in these creative works allow the family, community, artists and musicians along with the audience to walk in the footsteps of our Elders.

We speak their words and experience for a moment what it was like to be removed from Country, transported, fenced-in and locked up on a mission. The original poem, production and accompanying music also aids in demystifying removal, and not only builds empathy and understanding in audiences – but is also a call to action.

Lorina L. Barker receives funding from Australian Research Council and Create NSW

Julie Collins and Paul Smith do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.