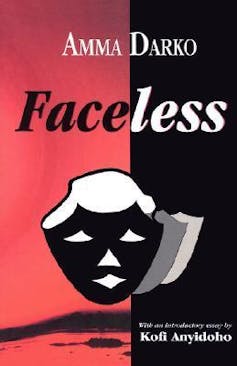

Amma Darko is one of Ghana’s leading novelists, known for exploring gritty social issues and the lives of women. There is much to be unearthed in the childhood narrative of deprivation and danger that she tackles in her 2003 work Faceless.

Faceless is the story of an investigation into the death of a young girl called Baby T, a child sex worker whose naked body is found dumped behind a marketplace, beaten and mutilated. During the progression of the novel, Darko skilfully reveals details about Baby T’s life through the eyes of her younger sister, Fofo, herself a street child.

In Faceless, Darko interrogates the seeming normalcy of the life of a street child by highighting the multiple complexities that children face in their homes, leading to some of them ‘choosing’ to live in the streets.

In as much as street children can be a result of dysfunctional homes, they are also created because of poor state policy implementation and broader structural inequalities. Darko reveals how violence shows itself in women’s experiences of gender inequality and impacts on their children.

We came together as a literary researcher and a psychology scholar to conduct a critical review of Faceless, a book that wrestles with the structural violence that bleeds into people’s homes, affecting their everyday experiences. The challenges of street children and gender inequities continue to stare at us, and Darko’s articulation of these issues 20 years ago continues to be relevant today.

The main argument in our reading of Faceless is that gender inequality provides fertile ground for violence and disorderliness. An understanding of its complexities is needed for societies to achieve social justice for women and children.

Who is Amma Darko?

The award-winning Darko is an important voice on the West African literary scene. She has published numerous books, including the novel Beyond the Horizon (1995), The Housemaid (1998), Faceless (2003), Not Without Flowers (2006) and Between Two Worlds (2015). Some of her books are published in both German and English, with two novels published in German only, the country where Darko was living when she established her literary career. In her novels, Darko focuses particularly on how women navigate the world, reflecting common Ghanaian life experiences.

Darko was born in 1956 in Koforidua, the capital city of the eastern region of Ghana. She grew up in the cosmopolitan capital Accra. After spending her formative years there, Darko moved to Kumasi where she obtained her diploma in industrial design in 1980. She also obtained a qualification in sociology and spent a year working at the Technology Consultancy Centre at the university in Kumasi.

In 1981, Darko moved to Germany because of the political instability in Ghana. She stayed there until 1987. It was in Germany, while doing menial jobs, that she wrote and published her debut, Beyond the Horizon. For Darko, Germany was a perfect space for her to focus, to think, and to develop her writing about her home country. She returned to Accra in 1987 to study accounting and continue writing novels that explore the impact of gender inequality on women’s lives and choices.

Gender and choices

Despite Ghana’s free education policy, gender plays a key role in access to formal education in a country where there still exist several factors that impact the education of adolescent girls. These are social, cultural and economic. In Faceless she writes:

In the traditional settings of our villages, cohesion and familiarity is so imbued in the lives of individuals that women are more conscious of what they do. But in the cities, there is a fragmentation, which results in behavioural flexibility. A woman like Fofo’s mother, whose ‘village’ happens to be inner-city Accra, is more likely to lose her sense of onus rather speedily when pushed by joblessness and poverty and the non-existent male support …

And so she lets Fofo and her sister Baby T take to the streets without much guilt. In the course of the novel Fofo meets a group of women who run a non-governmental organisation called Mute. It serves as a space for collecting and documenting community issues that no one is interested in recording.

However, their encounter with Fofo challenges Mute to shift from focusing only on documentation towards active involvement in bringing about change in the lives of the children who are living in the streets. Mute takes on Fofo’s case, unravels the mystery of the death of Baby T, and eventually rehabilitates Fofo.

This discovery of voice and a sense of self is important. Once Fofo finds these, her life is transformed.

Children like Fofo have had to grow up too quickly in order to assume the responsibilities their parents have abandoned. Presented as a social reject, Fofo grows to be the one who brings change into her life and provides peace and closure for her dead sister.

Tackling social ills

Darko unapologetically and courageously tackles the not-so-often talked about social ills that are persistent in many communities. She takes the reader on an uncomfortable but necessary journey.

With these persistent multiple challenges both in Ghana and other parts of the continent, we argue that Darko’s novel continues to be relevant today and her piercing narration cuts across borders.

Read more: A short story by Ghana's Ama Ata Aidoo offers a view of humanity's place in the world

Darko tells the real-life stories of those who are discarded, living on the fringe of society. The general population and government behave as if they do not exist, as if they are invisible, faceless.

But Darko gives them life and demands that the reader considers how they came to be in that place so that something can be done to give them a future.

Puleng Segalo receives funding from the National Institute for the Humanities and the Social Sciences.

Theresah Patrine Ennin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.