Banknotes and coins help shape our national identity. The images they display emphasise historical events, prominent personalities, or scientific, industrial and technological advances. Sometimes they highlight biodiversity, including distinctive plants and wildlife.

Our new research studied wildlife imagery on banknotes from across the globe. We wanted to find out how often native animals appeared, and which species were most commonly depicted.

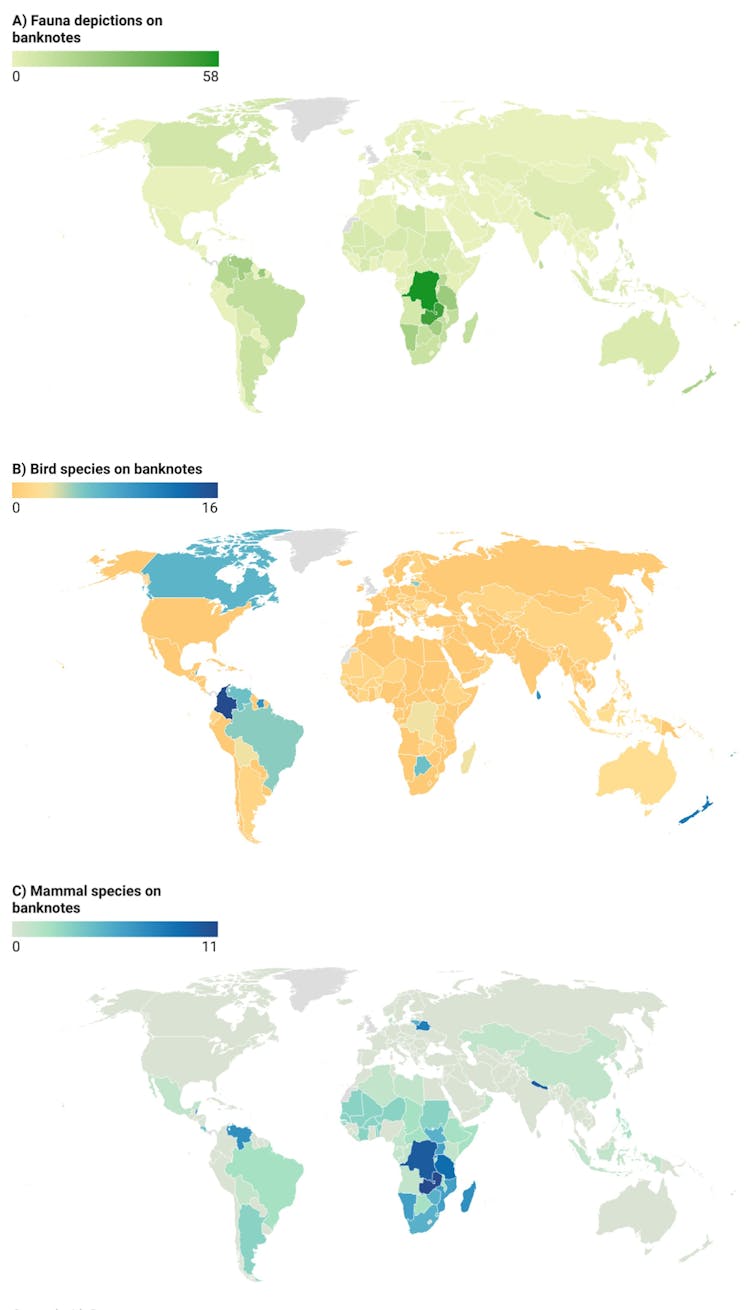

Almost one in six of the 4,541 notes we analysed, from 207 countries, featured wildlife. We identified intriguing patterns of use in different countries, from mammals in Africa and birds in South America to marine life in island nations. Some countries readily embraced wildlife, while others neglected them altogether.

Our research highlights an opportunity to raise public awareness of wildlife more broadly. In particular, showcasing threatened species on banknotes may lift their profile. This should be part of a broader conversation effort that builds community support for protecting biodiversity.

What we found

We trawled through a book titled Standard Catalog of World Paper Money and recorded every image of native animals on banknotes between 1980 and 2017.

Our analysis showed a wide range of animals depicted on banknotes. In most cases we could identify the species.

Images of wildlife appeared on more than 15% of the 4,541 notes we reviewed, from 207 countries. We identified 352 individual species.

In total, we found 883 depictions of native wildlife on 689 banknotes from 92 countries. That leaves 115 countries with banknotes devoid of wildlife.

Birds (195 species) and mammals (96 species) were the most widely used across all countries, followed by fish (25 species), reptiles (15 species) and invertebrates (15 species), then frogs or toads (6 species).

Significant differences existed among countries and regions. For example, currency from African nations frequently featured mammals.

In contrast, banknotes in South and Central American nations often featured birds. This reflects the higher diversity of birds in these tropical rainforest regions.

Island nations frequently depicted marine wildlife such as swordfish, whale sharks and green turtles. But they also included land-based species found only on these islands.

The results suggest that for many countries, native wildlife is valued and forms part of their national identity.

Some nations have started to make explicit links between animals depicted on their currency and their values and aspirations.

In South Africa, the Reserve Bank links the iconic “big five” native animals on their banknotes to its core values:

- rhino: protecting a shared future and accountability

- African buffalo: unity and cohesion through open communication

- African savanna elephant: stability, confidence and the building of social bonds to preserve respect and trust

- lion: leadership and guidance to achieve excellence

- leopard: independence, integrity and honour.

What about Australian currency?

Just two of the Australian notes in the series we analysed depicted wildlife. The $5 note has an eastern spinebill, while the $10 note has a sulphur-crested cockatoo.

However, more banknotes have been issued since we conducted our analysis. In 2019 the Reserve Bank added a bird to each banknote denomination, as well as an accompanying plant (typically an Acacia species). These images are part of the latest banknote security features, as follows:

Depicting threatened species

Almost a third (30%) of all wildlife depicted represented threatened species. For most groups of animals this is higher than the proportion of species currently listed as threatened with extinction. Species on banknotes include the critically endangered black rhinoceros, blue-throated macaw and hawksbill turtle.

In 2012, Fiji introduced a range of threatened species on their banknotes to raise awareness of their plight. So popular is their so-called “flora and fauna currency”, the community often refers to the notes by the species depicted on them, rather than the denomination. We have observed locals saying an item for sale costs a kulawai (red-throated lorikeet), rather than $5, or one nanai (Fijian cicada), instead of $100.

Australia could certainly do more to raise the prominence of our unique and threatened wildlife on its currency. Images currently used depict iconic and recognisable species – and not those most in need of conservation attention.

There is some evidence, albeit limited, to suggest featuring threatened species on banknotes may be used to aid their protection. For example, magazines published by conservation groups tend to use images of popular, attractive or well-known animals (“charismatic fauna”) that may or may not be threatened, to raise awareness and funds. Recent research analysing social media has also shown that sharing wildlife imagery led to direct conservation action.

And researchers have suggested advertisers using wildlife images should pay a fee, such as a royalty, which could then be spent on conservation efforts.

Looking beyond banknotes

Showcasing species on currency is an opportunity to foster national pride and raise awareness of each nation’s unique fauna. But for threatened species, there is no guarantee this will ultimately lead to their protection.

The depiction of animals on banknotes should be accompanied by other efforts to raise public awareness of their plight, such as education campaigns, public policy initiatives and fundraising drives.

More research is needed into the public impact of wildlife imagery on banknotes and how this might translate into conservation gains.

The authors wish to acknowledge the significant contribution made by Beaudee Newbery in collating and analysing the wildlife depictions on global banknotes as part of his research at Griffith University.

Guy Castley receives funding from the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, the Queensland Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, local councils and Griffith University. He is affiliated with the Glossy Black Conservancy and is a member of the Environment Institute of Australia and New Zealand, Society for Conservation Biology and BirdLife Australia.

Clare Morrison currently receives funding from the Queensland Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, local councils and Griffith University. She is a member of the Society of Conservation Biology, Australian Society of Herpetologists and advisor to the local conservation non-government organisation NatureFiji-MareqetiViti in Fiji.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.