By the early ’80s, Zebra had their ground game covered. Since forming in 1975, the hard rock trio comprised of singer-guitarist Randy Jackson, bassist Felix Hanneman and drummer Guy Gelso spent the better part of a decade playing the concert halls of their home base in New Orleans and in their adopted home of Long Island.

In the days before the internet could turn artists into overnight online stars, the hard-gigging band had amassed a significant and loyal following the old-fashioned way, playing shows three, four and sometimes five nights a week. And things were paying off.

“It was all through word of mouth,” Jackson says. “We’d play a show for a hundred or so people, and they’d go and tell their friends about this band they’d seen. The next time we’d play, we’d have double the number of folks at the gig. It just got bigger and bigger.”

By Jackson’s own admission, Zebra weren’t doing anything especially cool or revolutionary at the time; in fact, their setlists – healthy doses of Led Zeppelin, Yes, Jethro Tull and Pink Floyd, along with proggy, metallic-tinged originals sprinkled throughout – stood in stark contrast to the high-fashion synth-pop acts that dominated MTV.

Despite their impressive live drawing power, the band couldn’t get arrested when it came to label interest. They were seen as ’70s throwbacks, perilously out of step with current trends, and they were turned down by every record company around – multiple times, in some cases. Undeterred, the guys kept gigging away.

“I guess if we weren’t going so well locally, we would have gotten discouraged,” Jackson says. “We saw lots of other bands that couldn’t get signed, and they broke up because they simply didn’t have an audience to sustain them. We had our own thing going on. We could support ourselves. We bought houses. Other bands needed a record deal to keep going, but for us, it wasn’t a necessity.”

The members of Zebra had more or less resigned themselves to the idea of a label-free existence, but then something funny happened: One of their songs, Who’s Behind the Door? – a hooky, spacey gem that threw signature elements of Zeppelin, Yes and Floyd into a Cuisinart – was included on a Long Island radio station compilation album of local bands.

The track garnered big phones, and the buzz reached Atlantic Records, which had already rejected the band. Upon signing with the label, Zebra recorded their self-titled debut album with noted producer Jack Douglas (John Lennon, Aerosmith, Cheap Trick), and the double shot of Who’s Behind the Door? and the hard-charging Tell Me What You Want was catnip to AOR programmers. Within weeks of its release in March 1983, Zebra went gold and became the fastest-selling debut album in Atlantic’s history.

Unfortunately, the band’s descent was just as quick. Zebra’s second album, 1984’s No Tellin’ Lies (also produced by Douglas) stalled on the charts at number 84, and following the release of 3.V in 1986, Atlantic dropped the group.

“It’s hard to pinpoint any one reason why things went the way they did,” Jackson says. “The label probably didn’t promote us the way they could have. It would have been nice to have gotten more press, or better press.”

Sometimes you need to attract headlines – I get it. We didn’t have a Dee Snider or a Marilyn Manson in the band. Those are personalities that sell something beyond the music, but that was never us. All we ever had was the music

He also assigns part of the blame to the band’s wholesome, unprovocative image. “Sometimes you need to attract headlines – I get it. We didn’t have a Dee Snider or a Marilyn Manson in the band. Those are personalities that sell something beyond the music, but that was never us. All we ever had was the music.”

40 years after their ephemeral brush with fame, and nearly 50 years after their formation, not much has changed. Jackson did a short stint leading a solo band called Randy Jackson’s China Rain in the early ’90s, but by 1994 he regrouped with Hanneman and Gelso. The band issued a solid fourth album, Zebra IV, in 2003, and Jackson promises a new record is in the works. They get together for tours, but they don’t beat themselves up on the road like they used to.

“Our situation has always been unique,” Jackson says, “and it’s really because the fans allow us to do what we want. Our fans are our family, and we’ve always gotten along together.” He adds, “The band is family, too. Thankfully, we still get along.”

I understand you saw the Beatles when you were a kid.

We were friends with Twisted Sister. Jay Jay French would always call me after gigs and ask, 'How’d you do?' He was on top of things. The bands helped each other

“I did. My parents took me to see them in New Orleans when I was eight. I hadn’t seen any concerts at that point. I saw the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show – the girls were screaming. Seeing them live was really strange. You had the girls there, but their parents were there, too. I couldn’t hear the band, but somehow I could tell what songs they were playing. The sound system was pretty much the horns in the stadium. There was no low-end.

“I remember there was one girl near me who kept screaming for Paul the entire time. At the end, the crowd climbed over the rails and rushed the field, and that girl tried to make a break for it. Her father held her back and she screamed, 'Paul! Paul!' It was crazy. The funny thing is, I looked at all this and thought it was normal. Little did I know there was nothing normal about it.”

Were you a guitar-playing kid at that age, or did the Beatles light the fuse?

“I played piano, and I had a guitar and a Beatles chord book. I kind of taught myself. The Beatles’ songs were hard for me at that point. I could play the chords, but I couldn’t change them quickly. As I got older, things got easier. I listened to a lot of records and played along. I didn’t have anybody showing me what to do – I figured it out on my own. That’s what we did back then. Nowadays it’s so easy to learn guitar on the internet. All I had was my ears.”

Did you have a bunch of crap bands before Zebra?

“My brother and I had a band with another guy. This was in elementary school. We played a fair in our cafeteria. The woman who put it together asked if her son could play with us. It turned into a brawl, so that was kind of funny. We had all the elements of rock ’n’ roll going on.”

When you formed Zebra, were you pretty much set on the power-trio format?

“No, I wasn’t. Felix and I got together, and we had a five-piece – this was his band. It didn’t last long, and then Guy and I hooked up with a keyboard player. We did kind of progressive stuff. Felix was in a funk about his band breaking up, so I got him in with us as our bass player.

“We went out as a four-piece and played stuff by Yes and Jethro Tull and things like that. More and more, though, people wanted dance music, and our keyboard player wasn’t into it. He left and we started looking for a singer. We shared vocals on a lot of songs, but when we did Led Zeppelin, I would sing all the high parts.”

In the late ’70s, you guys headed to Long Island, where there were bands like Twisted Sister and the Good Rats. Was it a friendly scene? Competitive?

“It was competitively-friendly. There was a band called Rat Race Choir that we played shows with, and we all became great friends. We were friends with Twisted Sister. [Guitarist] Jay Jay French would always call me after gigs and ask, ‘How’d you do?’ He was on top of things. The bands helped each other. None of the bands were alike, so we weren’t really competing for the same crowds.

“It was a great scene. The drinking age was 18 and the places were packed. We were making a living. It went all week long – we were working all the time. For a while, we lived in one house, but before long we could afford our own places. We got married. I don’t think that kind of scene exists anymore.”

Even though you were making money, the labels didn’t care. Nobody wanted to sign you.

“It was crazy. Nobody wanted anything to do with us. It was a total shock when Atlantic finally signed us. Bob Buckman, the program director at this station WBAB, spoke to Jason Flom at Atlantic, and he became interested. Before then, all the labels said, ‘You’re dated. Your time is over. It’s a little old for us.’ If we weren’t doing so well, it would have been crushing, but we were playing to sold-out crowds.”

The press compared you to Led Zeppelin. Were the folks at Atlantic – home of Led Zeppelin – working that angle at all?

“I don’t think so. I never heard them say anything like that, though I know people in the press did write things like that. People have told me that when they heard Who’s Behind the Door? on the radio, they thought it was a Zeppelin thing. I think that had something to do with the open tuning I used and the sound of my voice.”

On songs like Tell Me What You Want, your solos have a Page-like quality, especially in your rather slurry legato.

“Yeah, sure. My guitar playing was greatly influenced by Page, but I never tried to copy him directly. He’s my guy as far as style goes.”

The band did a couple of albums with Jack Douglas. What was it like working with him?

“You know, at first, I didn’t know we needed a producer. I didn’t know what a producer even did. I mean, I saw on the records that George Martin produced the Beatles, but that’s about all I understood. The label said we needed a producer, so I put together a list of records I liked, and Jack Douglas had produced a lot of them.

“He did John Lennon’s Double Fantasy, which sounded so clean and beautiful. Then I found out that he did all of the Aerosmith records, so I thought, ‘He knows how to produce.’ He agreed to work with us, and he was great. We had a good time with him.”

Your debut album went gold. You must have thought, “We’re on our way!”

“We did. We thought it was going to be smooth sailing. The problem was, the songs we did on the first album we’d had for eight years. We had to scramble to come up with material for the second record. I had one song written, Lullabye, and the rest of the tracks were from bits and pieces that were knocking around, plus some things that didn’t make the first record.”

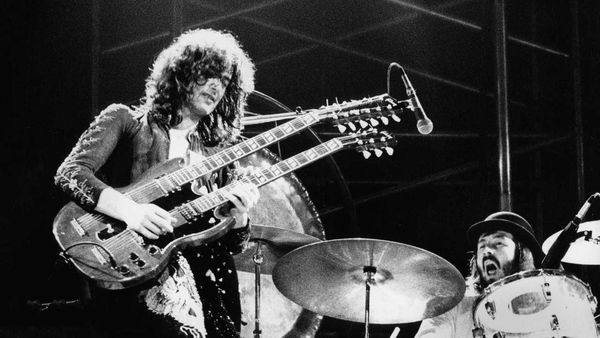

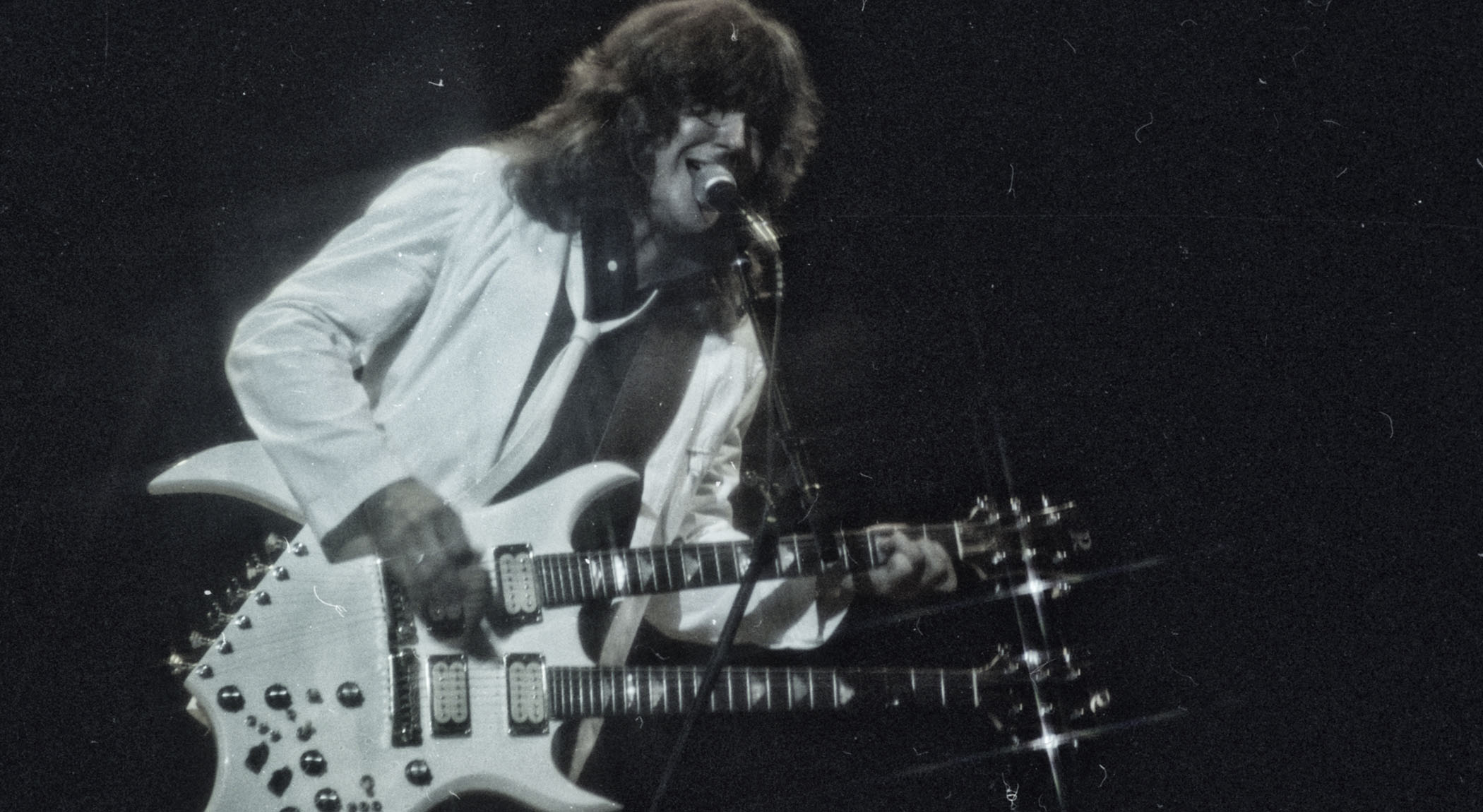

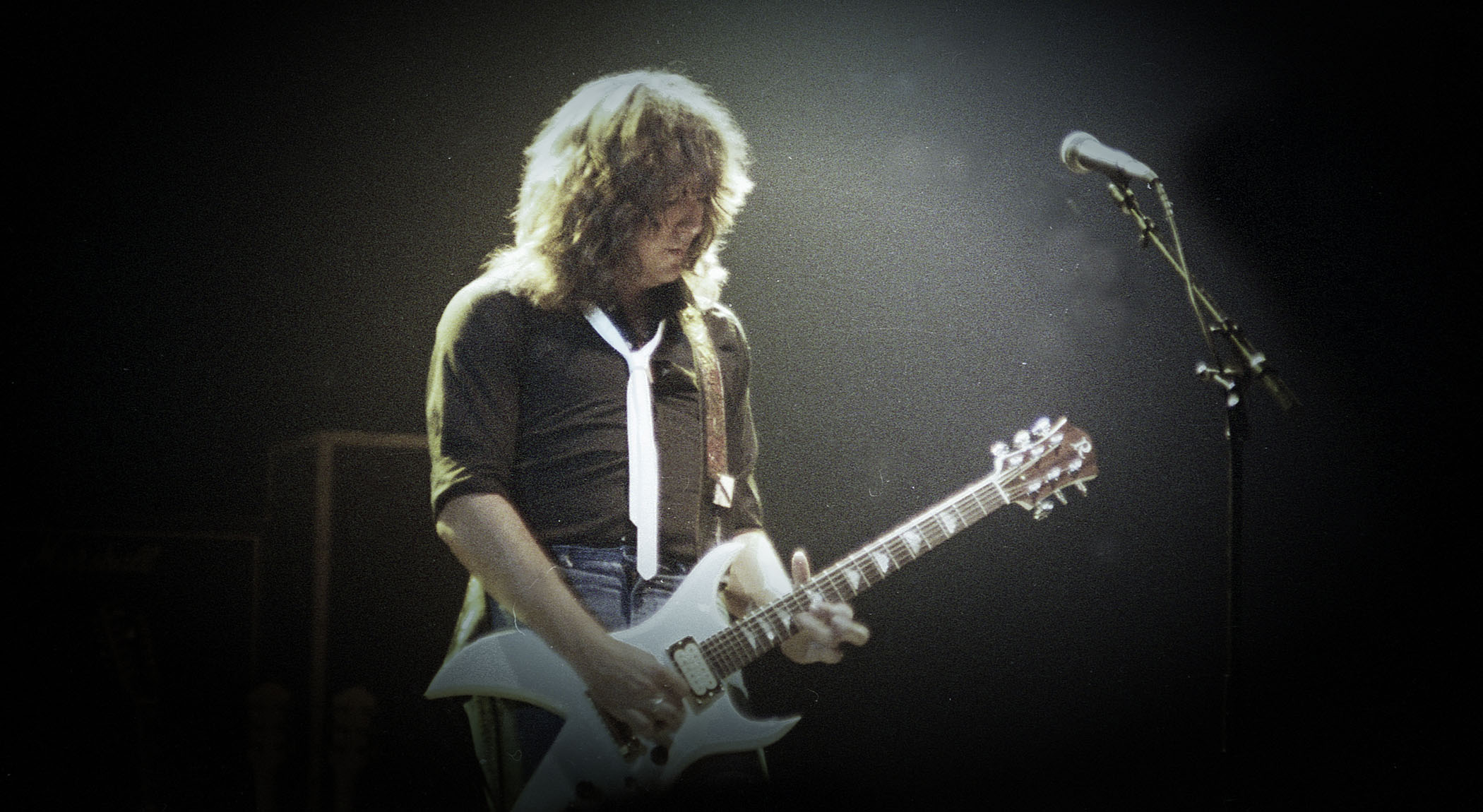

You were using a few guitars during this time – a B.C. Rich Bich, a black Gibson Les Paul Custom, a 12-string Guild acoustic. You even had a B.C. Rich doubleneck.

“I had the doubleneck, yeah. My favorite B.C. Rich got stolen – a Mockingbird Supreme. I never got to record with that one. Most of my recording was done with the black Les Paul. The Rich Bich was great, but it didn’t have the meat I needed in the studio.”

I loved Cream, especially their version of Crossroads. I learned a lot of Hendrix. And the Allman Brothers Band – I learned as much of their music as I could

Around the time of the band’s third album, hair metal was coming in and there was a big emphasis on videos and hit singles. Did Atlantic put pressure on you guys to sharpen up your image or hire outside songwriters?

“None. No pressure at all. I stopped drinking and wrote a ton of material. We had more than enough songs for the third album. Atlantic even approved us to produce ourselves. We thought it came out well, we were very happy with it, but it just didn’t seem to hit with the public. You never know about these things.”

After Atlantic dropped the band, you all hit pause for a bit. You never actually broke up, though.

“We never broke up, no. We were doing a few things on our own, and I was writing songs with Mark Hitt from Rat Race Choir. Eventually, Atlantic came back to me and wanted to do a solo deal, but by that time Zebra came back together and started playing shows again. There was a lot of demand for us. We finally got around to making a fourth album, which we did on our own. We were excited again.”

You mentioned Jimmy Page as your “go-to” guy. Any other guitarists you can point to as big influences?

“Mark Farner. He’s the guy I really listened to a lot. He played great parts, but they weren’t that difficult. I couldn’t do everything he did, but I could pick out most of his stuff. It made me feel good. I loved Cream, especially their version of Crossroads. I learned a lot of Hendrix. And the Allman Brothers Band – I learned as much of their music as I could.”

The influences one has in their teens sort of stick, but later in life, did you hear anybody who impacted you?

“I have to say no. Not because they weren’t doing anything good, but because I wasn’t paying attention. I heard various things, but there wasn’t anything that grabbed me and made me feel like I needed to learn it.

“Eddie Van Halen came along, and he was an influence on me overall. He was right in my age group, and his band came up the same time as Zebra. After that, there really hasn’t been anybody. A lot of music that came out after the ’90s didn’t seem to have that much guitar.”

So… Zebra is working on a new album – finally.

“Finally, right. We’ve been working on a record for 20 years. [Laughs] In fact, as soon as we finish this interview, I’m going back to it. I’ve got so much material – hopefully enough to make a great album. I don’t want to spend my whole life going through it all, but I could easily do that.

I’ve got stuff to do that I never had to deal with before. I’ve got grandkids!

“I’ve got a blues song that isn’t just I-IV-V, so that’s cool. Lyrically, the record’s got an older perspective to it. [Laughs] And I’m going to have a few songs that are reminiscent of the first album. People keep telling me they love that record, so I’m going to give them some things in that vein.

“With any luck, there will be an album after that. It’s hard getting everybody in the frame of mind to do this. I’ve got stuff to do that I never had to deal with before. I’ve got grandkids! Time goes by and you want to hang with them while you can. But yeah, we’re still making music. We’ll get this record out there soon enough.”