“I can remember sitting in a London coffee bar with Eric Clapton, when we first formed Cream, and telling him how I wanted us to take the language of the blues and develop it further,” Jack Bruce told Bass Player. “How presumptuous – this kid from Glasgow, talking about an African-American art form that transcends music!”

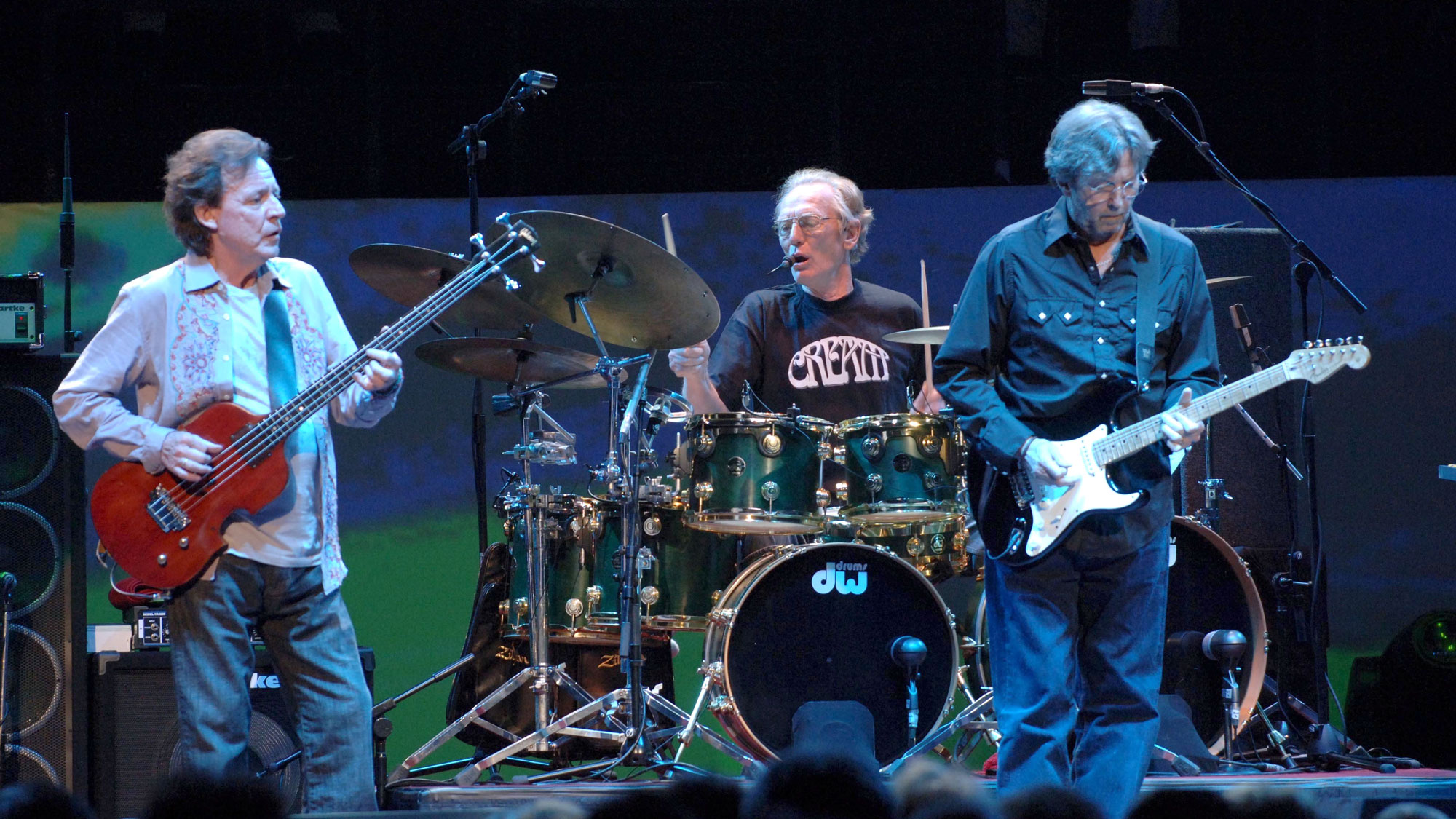

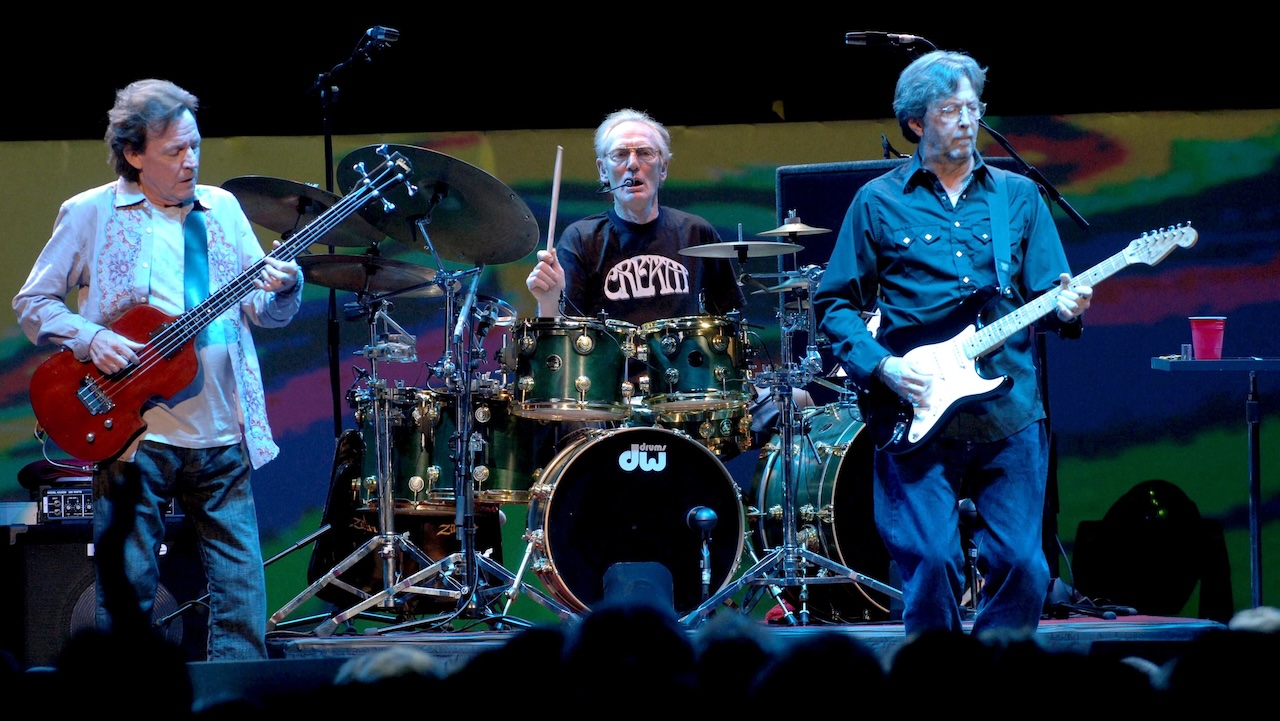

Of course, in retrospect, Cream rose to its own lofty level as the world's first supergroup. In its brief (1966-68) initial incarnation, the pioneering power trio not only expanded the blues and exposed the idiom to the masses, it obliterated rock & roll's boundaries, extending improvisation and shattering the supposed sonic limitations of three rock musicians.

Cream scored huge hits with Sunshine of Your Love and White Room. Clapton became a guitar god, and Ginger Baker a confrontational force on and off the drums. But it was Bruce – at times overshadowed by the two, even though he was the lead vocalist and main songwriter – who stirred this strange brew with a heaping spoonful of vision and an equally progressive bass style.

And while it took only 28 months and four albums to forge the a new musical foundation for countless like-minded bands, it took 36 years (not counting a three-song performance at Cream's 1993 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony) to get the trio back together for a series of shows in 2005.

The 21st-century edition of Cream reflected each member's post-Cream career experiences. Although the energy of their youth will never be duplicated, Clapton – through his numerous collaborations and solo CDs – had never been a brighter star or more profound guitarist, and Baker, though living in semi-retirement in South Africa, sounded better than ever.

Bruce had traveled the most interesting route, from his brilliant piano-oriented early solo albums, and other power trio formats, to his cutting-edge work with Tony Williams Lifetime, Frank Zappa, Kip Hanrahan, and his Afro-Cuban-infused band, the Cuicoland Express. He also endured a liver transplant in 2003 due to cancer, which eventually took his life in 2014. All told, the onstage result was a new bass approach: wider and deeper in support, range, and tone.

We spoke with Bruce in 2005 just before the trio's three New York shows at Madison Square Garden, to get the inside story on life and bass playing in Cream, now and then.

Can you compare and contrast your thoughts at the first reunion rehearsal versus the first night at Royal Albert Hall?

“Both were indescribable, and completely different. For me, the stress and tentativeness started before I went into rehearsal. It was raining, and I knew Eric wasn't there yet, but someone said Ginger was inside. So I went in to see what the vibe was, and it was great – very pleasant, and it continued like that.”

“The Royal Albert Hall was incredible. I'm always nervous before a show, but this one took my breath away, sent shivers up my spine, the whole bit. Eric said, ‘Okay, you go first, Jack,’ because I was on the far side of the stage however, my legs didn't seem to want to do that! But the warmth of the audience was phenomenal, and when we began playing, that was it – no problems.”

How did the rehearsals go?

“When I knew they were coming up, I went through all the albums, demos, gig and rehearsal tapes – anything we'd ever tried. I wrote down everything we played and I was surprised; I always thought Cream knew only a handful of tunes, but there were quite a lot of songs.

“In rehearsal we discussed each song and whether we wanted to try it; we tried a lot of songs that didn't end up among the 19 we performed. There were songs I felt we should do, like I Feel Free, that other members of the band vetoed – obviously it's a democracy now!

“We rehearsed five days a week for three weeks, but opening night was the first time we played the set from beginning to end, so there was some adventure there.”

How has your bass playing changed since Cream, and how did that affect the way you approached the bass parts?

“At the Royal Albert Hall shows I realized it has changed more than I ever thought. I found myself playing this sort of flamenco bass style with strums and chords and drones, not just lines. It just kind of happened, as a way of fulfilling the role I feel I have in the band now. A good example is the solo sections on N.S.U, Deserted Cities of the Heart, and Badge.

“Because it's a trio, it's almost like I'm playing a big rhythm guitar – as opposed to the first time around with Cream, when I played a more lead bass style. I'm hoping to develop the concept further.”

You used your middle finger a lot.

“I had a terrible blister on my index finger, and I was using whatever was working! Normally, I'd be alternating my first two fingers more.”

You sounded strong vocally, and all of the songs were in their original keys.

“We didn't change any keys, not even Badge, because I'm a great believer in a song's key having a real meaning in its own right. I was quite surprised at how strong I was vocally, considering that after my illness about a year earlier I couldn't even talk. I'd had tubes in my throat, and when they were taken out I wasn't able speak; I had to re-learn how.

“When they asked about a Cream reunion I said yes right away, but I probably had to write it! As rehearsals drew closer, I found this amazing voice teacher in London, Mary Hammond, and we worked on vocal exercises every week.”

How did you choose your basses for the shows? Did you consider using your Gibson EB-3?

“I had tried the EB-3 some years ago, and I found the short scale length to be like playing a toy. I literally couldn't do it anymore – was hitting wrong notes because it was just too small. I've been using my fretless Warwick forever; it's my favorite bass, and I've been playing Cream songs on it with my own band, so I knew I would stick with it in some capacity.

“As for the Gibson EB-O, I've just fallen in love with it over the years. It's got a real deep, woofy sound. I think I got it from luthier Dan Armstrong, and I had some work done on it to keep it in shape. Then when I was playing with Ringo Starr in the late '90s, I discovered you just can't play a fretless on those old Beatles songs. On tunes like A Little Help From My Friends, Paul had a certain sound and feel on his Hofner, so I started playing the EB-O to recreate that.

“With Cream, I was going to switch between the two, tune by tune – but that seemed silly, so I looked at the setlist and decided to start on the EB-O and switch to the Warwick halfway through, after Rollin' and Tumblin', where I just play harmonica.

“Also, I had suggested to Warwick that they make a special bass – a nod toward my old EB-3 – to celebrate this event. We haven't gotten it quite right yet, but the prototype was onstage and can be seen in the DVD.”

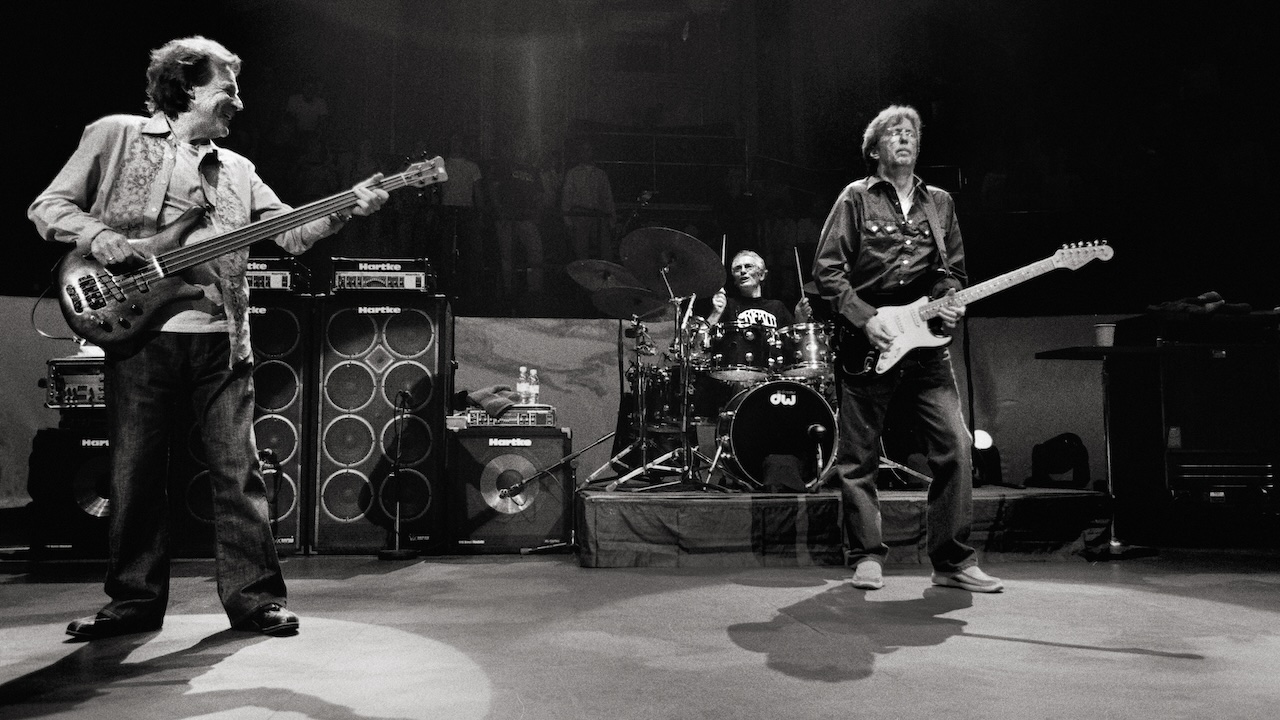

How did you select your amplification?

"I hired a big rehearsal room in London and I got Beet, my bass tech, to bring in every bass amp in existence. It was great fun; I had a wireless setup, so I could switch quickly from one amp to the other. And what I ended up liking the best was my Hartke gear. I've known those guys forever, and in addition to Jaco's input, their gear was developed with me in mind. They used to do my sound quite a bit, when I was using all sorts of components and blowing speakers right and left.

“The main change is that I'm using their paper-cone 8x10 cabinets, along with the aluminum 1x15s and the heads. It all sounds great – like a good Marshall stack back in the '60s. Most of the other amps I tried were very good, but they just didn't sound like me.

“In the original Cream we had Marshall stacks with only one or two speakers working; that's what gave me my trademark distorted tone. On 90 percent of the gigs there was no proper PA or any monitoring, so the sound we got was the sound onstage. In order to generate the kind of excitement we wanted, we had to play really loud and create that sound with our gear. Nowadays sound technology is spectacular, and we aren't loud at all onstage. Technology has caught up with and surpassed the music.”

What did you think of how the band sounded at the Royal Albert Hall?

“I was astonished. It felt really fresh and natural – that was what amazed us all, from the start of rehearsals. It sounded different; it sounded like now. It reflected how much we've grown, and how much we brought back to the band from all the projects we've done.”

“I would say, with certain reservations, that it's a better band now than it was then. Our time and feel is better and we've matured; we're not trying to prove anything to anyone or to each other. There's a lot more respect and honesty, in a way – and, not to get maudlin, but there's a lot of love as well. After one of the shows, Ginger said to me, ‘You are a great bass player after all.’ I couldn't believe it – he’d never once said that in all the years.”

You've played with Ginger on and off since Cream. How was he the same and how was he different?

“He's still Ginger – but he has a precision about his playing now that's difficult to put into words. He was always great, but he's even better. When we did BBM in the early '90s, he was well ahead of his Cream days, but there's something more he's brought to his playing. I think he's the key to the band sounding good now.”

Do you and Ginger naturally play in the same place in the pocket?

“I don't think we ever analyzed that; if we did, we might not be able to play together! I've always found it very easy to play with him, so I would say yes. I know that in Cream we both used to speed up; we'd get to the end of a long improv and I'd be wracking my brain to remember what the song was! Now it feels more relaxed and settled, like the way we're doing Crossroads: It's not an uptempo killer number anymore. It's more reflective.”

“I've always subscribed to Charles Mingus's concept of time, which he called rotary perception. It says there's a constant, metronomic time in your head. When you have a medium tempo, you play right in the middle of the meter in your mind; when you have a fast tempo, you play slightly in front of the meter; and when you have slow blues or a ballad, you play slightly behind the meter. The key is the ability to move within that meter. You can slow down or speed up phrases and accents, all while your internal time is constant.”

What's the same and what has changed about Eric Clapton's playing?

“Eric is quite incredible; sometimes I would find myself just standing there watching him, because he hasn't played like this since back then. I don't mean he hasn't played great, but he hasn't had to play the demanding role in Cream, where he just can't stop or take a break ever!

“He's playing rhythm and lead all at the same time, more or less. Recently, he's had proper bands with keyboards and other guitarists, so he can sing and play lead, but here he's back to covering it all. He's definitely better, too, but again it's hard to explain how. We added Stormy Monday, which Cream never covered, as a vehicle to showcase Eric as he's become.”

The band didn't make many changes to the forms of the songs, and you avoided long improvisational sections that were a trademark of Cream shows.

“Most of the songs were sort of carved in stone, and to change them made little sense. As for the solo sections, we wanted to improvise, but we didn't want to go too long. That was a thing of the time, and I don't think it would be valid now. We wanted to avoid a nostalgia trip, where we break out the Marshall stacks and the psychedelic clothes. We didn't want to be a tribute band to ourselves!”

Some critics maintain that Cream's long jams in the '60s were self-indulgent and overshadowed the band's best side – the concise studio recordings of forward-thinking original songs.

“I tend to agree. There were two sides to the band. Once we got to eight tracks on the second album, we saw the possibilities of the studio, with overdubs and my ability to play keyboards – while live, we saw the opportunity to achieve something different. Both sides were equally valid, when they worked.

“In a sense, the band lost its way with the long jams, and that became a sort of albatross. It was our version of the Who smashing gear. They got tired of that quickly, we didn't get tired of it, but it got tedious. I'm sure there were times when Ginger thought, ‘Oh, now I've got to play this long drum solo.’”

What was your bass approach on Cream records?

“Well, the great aspect of recording is you have some time to work out the basslines. You're not improvising; it's sort of re-composition, if you like. You perfect the part on run-throughs.

“Badge is a good example; we had the whole day to get it down-it was the most number of takes we ever did. My goal was always to create a bassline where, if you took away or changed one note, the whole song would collapse. I tried to carve the part out of the music, like a statue, so that I knew it would last.”

How about your approach during the live extended jams?

“I would start off supporting Eric, all the while playing with Ginger, and then I would build and almost goad Eric to reach the heights of his playing – and when that happened, I would take off as well.

“If you think of the first live version of Crossroads – which was maybe the best example of what the band was like live then – we start up high and stay up high. On others, like Spoonful, we were trying to get this primeval, big vibration that just lasts. I would use 5ths, chords, and countermelodies to fatten things up, because when Eric would play high, above my bassline, it left a lot of space in the middle. But, as I said, it was with more of a lead-bass attitude.”

That brings to mind the way you bent your strings by a step-and-half.

“That was from seeing the way Eric played. When I got the EB-3, my thinking was: Well, it's a bass guitar. I wanted to emphasize the guitar aspect, which is why I put light-gauge La Bellas on it, for string bends. I was familiar with traditional forward-and-backward vibrato from playing cello and string bass, and I played the Fender VI with Graham Bond, to cover the guitar range when John McLaughlin left the band – but with Cream it was a whole new direction.”

Any chance of an album of new Cream material?

“It's something I'd love to do; it would be a challenge to try to create music that would stand up to the classic songs. I've got a few ideas already – in fact, I wrote a song yesterday that I think would work. I just don't know if it will happen.”

“We've had offers you wouldn't believe – didn't believe – for long world tours, and it's tempting. But none of us wants to accept because it would take away from the rarity and special nature of getting together. I'd like to do it every now and again and just play somewhere, but we could do an album amidst that, and I'm going to suggest it.”

What light can you shed on your illness?

“It was quite an ordeal. The liver transplant was successful, but then I developed infections and it was touch and go for a while. The experience didn't make me any more religious, but I now believe in the power of prayer. So many people were rooting and praying for me, and I could literally feel that, even when I was in a coma. My wife would constantly whisper all of those good thoughts to me. I want to encourage other people that you can actually go through a terrible illness and recover and get back to your life.”

What other projects and plans lie ahead?

"I've got to do the third in my series of Latin-themed albums with my own band, which I'm hoping to do early next year. I have some material in the can, and I'd like to do some recording in Cuba. Otherwise, I'm just very happy to be here, and to be a member of a band. Right now, that's the best feeling of all.”