With the rising spectre of the loss of women’s reproductive autonomy in the United States, it’s timely to consider why abortion is an important and necessary part of pregnancy and fetal care. More consideration needs to be given to women and their partners who have a need for abortion due to serious fetal problems that will lead to early death or profound disability in their children.

Few enter into pregnancy with the idea that something could go wrong with fetal development, but approximately one in 25 infants are born with a birth defect. And as a medical geneticist, I would like to focus on the much higher risk (often one in four) of recurrence of an inherited disease.

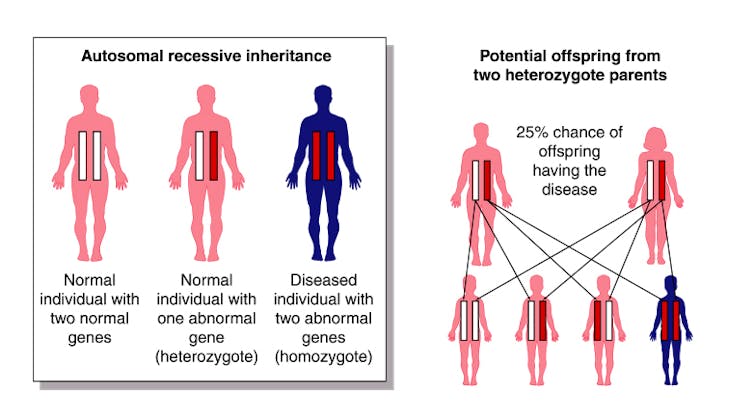

Statistically, each of us is more likely than not to be carriers for a disorder that would be lethal before adulthood. As carriers, we are not affected by disease, but are at risk of transmitting the disease to children if a partner is also a carrier. At present, any of us could be at risk, but we just don’t know.

To put it into human terms, consider as an example my least favourite genetic disorder, SURF1 deficiency, which occurs in about one in 40,000 births. Affected fetuses develop normally, have an unremarkable birth and early infancy, learn to walk and speak and then begin quite literally to stumble. They typically come to medical attention at around 18 months of age, are diagnosed at age two, and half of them die by the age of five years.

It’s a horror for sure, but now consider that these children retain normal cognition as their body fails. Looking into the eyes of a four-year-old who understands that they are dying is hard for me when I see them in clinic every few months, but their mothers must do this every day.

Abortion is a critical option

For families that have experienced a serious inherited disorder, subsequent pregnancies are traumatic. Abortion is a critical option, a security feature that allows them to consider having children again. Entering into a pregnancy with the intent to terminate one-quarter of the time may be hard for most people to understand, but for affected families it is a safe option when the alternatives are devastating.

It is true that there are other options. Families can consider the use of donor sperm or egg. They can attempt the pre-implantation diagnosis of embryos created by in vitro fertilization. They can adopt. But all of these options may create financial, social or moral burdens that some women find impossible.

The important principle is that women and their families have all options available. We, as a society at large, are not relevant and should have no interest or opinion in the decisions they make.

Gestational age and diagnostic timelines

Abortion should remain legal, and it should not be limited by gestational age. I won’t hide my personal belief that abortion should be available without exception up until the time of delivery. This view has largely been formed by watching children die of untreatable disease.

The discovery of serious problems in a pregnancy can’t be subjected to a tidy timeline. Many diagnostic procedures that identify serious problems occur later than we would like them to, but this is what biology allows us.

Efforts to limit access to abortion late in pregnancy are particular in their cruelty to women carrying fetuses with congenital defects. These restrictions are often used as a gateway to eliminate women’s reproductive freedom, and will be in the United States.

It could be argued that the number of people affected by this problem is small. However, their exceptional voices risk being drowned out by a noisy debate about abortion. I am bothered by abortion debates being framed wholly in terms of the word “choice.” These women never asked to be put into this situation, and their rights, options and dreams must also be considered.

Neal Sondheimer is a member of the board of directors of the MitoCanada Foundation, a non-profit supporting patients and families with mitochondrial disease and research into therapy. He serves on advisory boards for Jaguar Gene Therapy and Moderna.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.