The Kingdom of Tonga exploded into global news on January 15 last year with one of the most spectacular and violent volcanic eruptions ever seen.

Remarkably, it was caused by a volcano that lies under hundreds of metres of seawater. The event shocked the public and volcano scientists alike.

Was this a new type of eruption we’ve never seen before? Was it a wake-up call to pay more attention to threats from submarine volcanoes around the world?

The answer is yes to both questions.

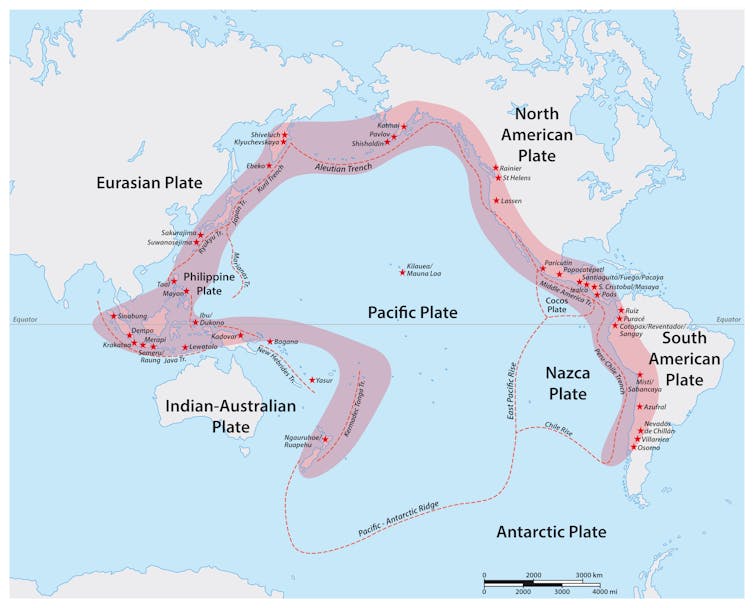

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano was a little-known seamount along a chain of 20 similar volcanoes that make up the Tongan part of the Pacific “Ring of Fire”.

We know a lot about surface volcanoes along this ring, including Mount St Helens in the US, Mount Fuji in Japan and Gunung Merapi of Indonesia. But we know very little about the hundreds of submarine volcanoes around it.

It is difficult, expensive and time-consuming to study submarine volcanoes, but out of sight is no longer out of mind.

Read more: Why the volcanic eruption in Tonga was so violent, and what to expect next

Tongan eruption breaks records

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption has firmly established itself in the record books with the highest ash plume ever measured and a 58km aerosol cloud “overshoot” that touched space beyond the mesosphere. It also triggered the largest number of lightning bolts recorded for any type of natural event.

The injection of large amounts of water vapour into the outer atmosphere, along with “sonic booms” (atmospheric pressure waves) and tsunami that travelled the entire world, set new benchmarks for volcanic phenomena.

COVID hampered access to Tonga during the eruption and its aftermath, but local scientists and an international scientific collaborative effort helped us discover what drove its extreme violence.

Eruption creates a giant hole

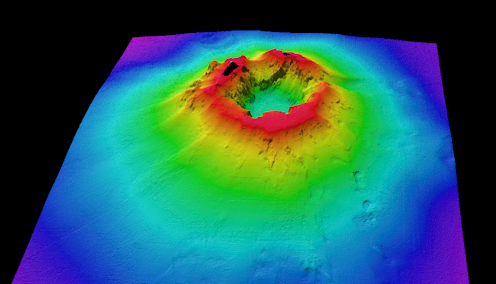

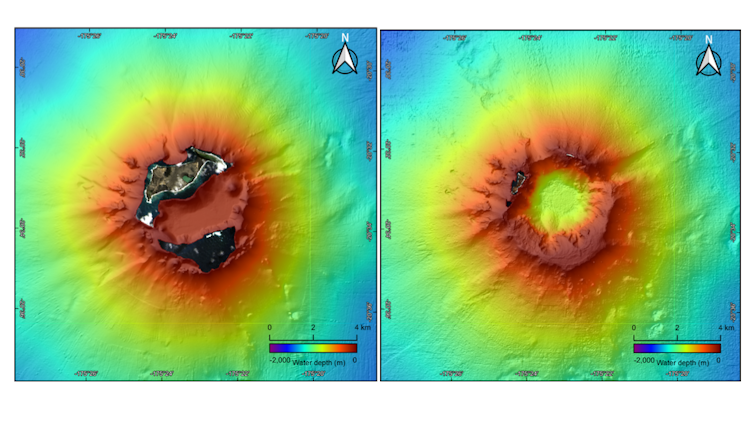

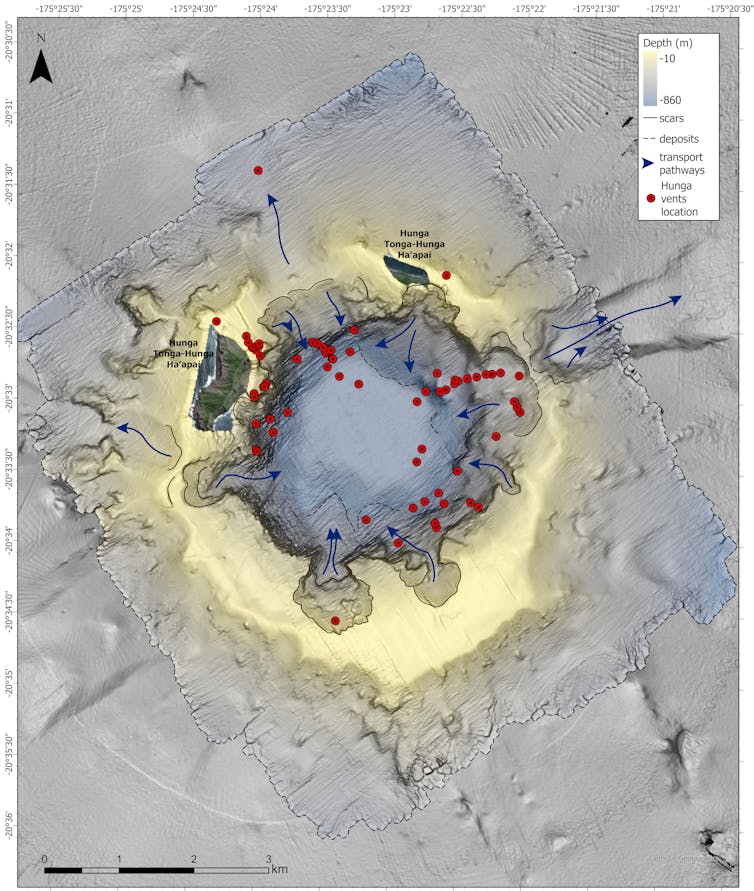

A team from the Tongan Geological Services and the University of Auckland used a multi-beam sonar mapping system to precisely measure the shape of the volcano, just three months after the January blast.

We were astonished to find the rim of the vast submarine volcano was intact, but the formerly 6km diameter flat top of the submarine cone was rent by a hole 4km wide and almost 1km deep.

This is known as a “caldera” and happens when the central part of the volcano collapses in on itself after magma is rapidly “pumped out”. We calculate over 7.1 cubic kilometres of magma was ejected. It is almost impossible to envisage, but if we wanted to refill the caldera, it would take one billion truck loads.

It is hard to explain the physics of the Hunga eruption, even with the large magma volume and its interaction with seawater. We need other driving forces to explain especially the climactic first hour of the eruption.

Mixed magmas lead to chain reaction

Only when we examined the texture and chemistry of the erupted particles (volcanic ash) did we see clues about the event’s violence. Different magmas were intimately mixed and mingled before the eruption, with contrasts visible at a micron to centimetre scale.

Isotopic “fingerprinting” using lead, neodymium, uranium and strontium shows at least three different magma sources were involved. Radium isotope analysis shows two magma bodies were older and resident in the middle of the Earth’s crust, before being joined by a new, younger one shortly before the eruption.

The mingling of magmas caused a strong reaction, driving water and other so-called “volatile elements” out of solution and into gas. This creates bubbles and an expanding magma foam, pushing the magma out vigorously at the onset of eruption.

This intermediate or “andesite” composition has low viscosity. It means magma can be rapidly forced out through narrow cracks in the rock. Hence, there was an extremely rapid tapping of magma from 5-10km below the volcano, leading to sudden step-wise collapses of the caldera.

Read more: Tonga eruption was so intense, it caused the atmosphere to ring like a bell

The caldera collapse led to a chain reaction because seawater suddenly drained through cracks and faults and encountered magma rising from depth in the volcano. The resulting high-pressure direct contact of water with magma at more than 1150℃ caused two high-intensity explosions around 30 and 45 minutes into the eruption. Each explosion further decompressed the magma below, continuing the chain reaction by amplifying bubble growth and magma rise.

After about an hour, the central eruption plume lost energy and the eruption moved to a lower-elevation ejection of particles in a concentric curtain-like pattern around the volcano.

This less focused phase of eruption led to widespread pyroclastic flows – hot and fast-flowing clouds of gas, ash and fragments of rock – that collapsed into the ocean and caused submarine density currents. These damaged vast lengths of the international and domestic data cables, cutting Tonga off from the rest of the world.

Unanswered questions and challenges

Even after long analysis of a growing body of eyewitness accounts, there are still major unanswered questions about this eruption.

The most important is what led to the largest local tsunami – an 18-20m-high wave that struck most of the central Tongan islands around an hour into the eruption. Earlier tsunami are well linked to the two large explosions at around 30 and 45 minutes into the eruption. Currently, the best candidate for the largest tsunami is the collapse of the caldera itself, which caused seawater to rush back into the new cavity.

This event has parallels only to the great 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia and has changed our perspective of the potential hazards from shallow submarine volcanoes. Work has begun on improving volcanic monitoring in Tonga using onshore and offshore seismic sensors along with infrasound sensors and a range of satellite observation tools.

All of these monitoring methods are expensive and difficult compared to land-based volcanoes. Despite the enormous expense of submarine research vessels, intensive efforts are underway to identify other volcanoes around the world that pose Hunga-like threats.

Shane Cronin receives funding from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, through the Endeavour Fund (UOAX1913 and UOAX2213). Results described in this work includes work in progress in collaboration with Dr Marta Ribo (Auckland University of Technology, NZ), Prof James Garvin (NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre, USA), Prof Frank Ramos (New Mexico State University, USA), Dr Sung-Hyun Park (Korean Polar Research Centre, Republic of Korea) Drs Joali Paredes, Jie Wu, Ingrid Ukstins and David Adams (The University of Auckland, NZ) and Taaniela Kula (Tongan Geoscience Services).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.