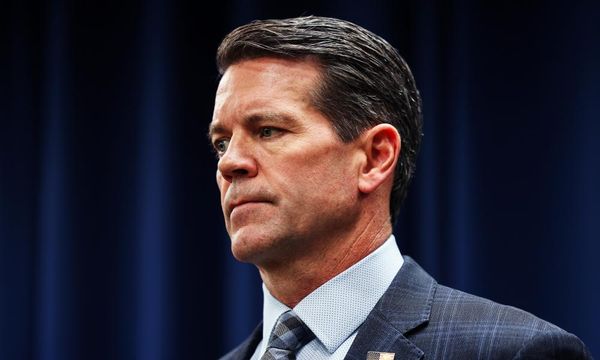

Juan Carlos Silva has sketched hundreds of faces.

When he left his native Venezuela in 2020, Silva earned money by drawing portraits of locals and tourists in the South American nations he visited in search of opportunity.

“With no work, no money, I survived on my art,” Silva said. “I started to draw in the public squares. I didn’t have anything else that I could do.”

He spent months in Colombia and Ecuador, passed through Brazil and Chile, carrying his art supplies with him. Seeing no chance for long-term prosperity in South America, Silva made the decision to make the arduous trek north to the United States.

Silva arrived in Chicago from San Antonio, Texas, last month, becoming one of thousands of asylum-seekers the city has taken in since August. He’s also one of the hundreds of migrants who have had to spend nights sleeping on the floors of the city’s police stations.

The 46-year-old former military man is staying in the lobby of the 22nd District Police Station in Morgan Park. And the discomfort has fueled his artistic spirit. Silva is lending his talents to the Edna White Community Garden, next door to the police station, volunteering to paint the garden’s sheds and benches.

He’s also using the space to hone his craft, channeling his migration experience to create new works.

“I think artists need to experience suffering to get the best out of them,” Silva said.

Kathy Figel, executive director of the garden, has collected donations for asylum-seekers and has invited those moving in and out of the police station into the garden. That’s how she met Silva.

Figel said she had to use Google Translate to communicate with Silva when he offered to paint the garden’s benches. The two eventually decided to look to the sun and sky as motifs. When Silva finished the benches and sheds, he asked for more.

But Figel recognized Silva’s talent and instead suggested he use the garden space as his studio and paint what he wanted.

“You need to work on your own self, what do you want to paint? Tell a story with your painting,” Figel told him. “Send a message.” She put a call out to the community for donations of painting supplies for Silva, and people responded.

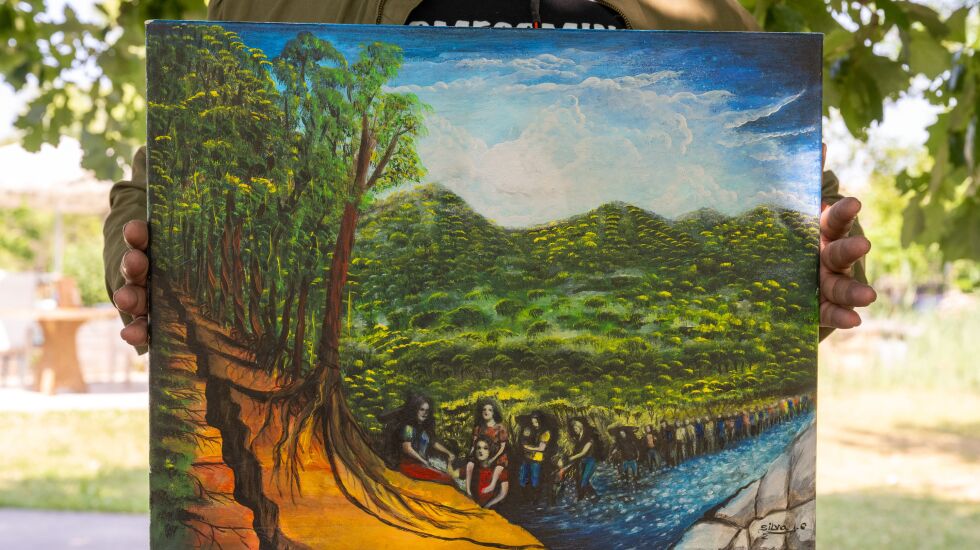

Silva created “The Jungle of Darien,” which depicts a row of immigrants walking along a river, surrounded by imposing mountains and lush, dense canopy. Darien National Park is a mountainous region that sits on the border between Panama and Colombia.

Silva remembers the stretch of dense mangroves, cloud forests, swamps and rocky coastline as one of the toughest to endure on his journey north.

The painting “is a tribute to the immigrants, it’s a tribute to their pain,” said Silva. “It’s hours and hours, days and days of walking, with the hope of arriving alive to a place where no one is waiting for you and nothing is guaranteed. They are walking only with hopes and dreams.”

Silva said it’s the first time he’s really felt free to express himself through his art. As a child, he learned rudimentary techniques from a painter in his hometown, but his family discouraged him from pursuing art professionally, believing it wouldn’t provide a living.

“They tell you that you’re going to die of hunger if you decide to pursue art,” Silva said.

Instead, Silva became a lawyer and joined the military in Venezuela, where part of his duties included helicopter maintenance. He honed his painting talent at home, learning by copying great works from noted artists, Silva said. He’d spend long hours on a single project.

Silva spent more than 20 years in the military, where he reached the rank of first sergeant. However, he became concerned over the direction the country was headed in and how the government treated its own people.

“The police and military institutions became full of corruption, and it became dishonorable to wear the uniform, to represent an institution that inflicted a lot of pain on the population.”

He decided to desert. Silva said he was detained for several days after he left. When he was released, he figured it would be safer to leave the country and began his trek through South America.

Now that his journey has led him to the United States, Silva said he hopes to continue improving his craft and wants to be able to work so he can contribute to his new homeland.

“Once we arrive at a different country, no matter where it is, we have to contribute to that society,” Silva said. “We can’t just work as hard as we did in Venezuela, we have to double it. When we emigrate, we know we won’t get eight hours of sleep anymore. We have to give one-thousand percent until we find ourselves back in peace and comfort.”

Silva will be showcasing his work Sunday at the Summer Solstice Uprising Market & Art Festival at Morgan Park Academy.