In August 1998, 700 people came to Boulder, Colorado, to attend the founding convention of the Mars Society. The group’s co-founder and president, Robert Zubrin, extolled the virtues of sending humans to Mars to terraform the planet and establish a human colony. The Mars Society’s founding declaration began, “The time has come for humanity to journey to the planet Mars,” and declared that “Given the will, we could have our first crews on Mars within a decade.” That was two and a half decades ago.

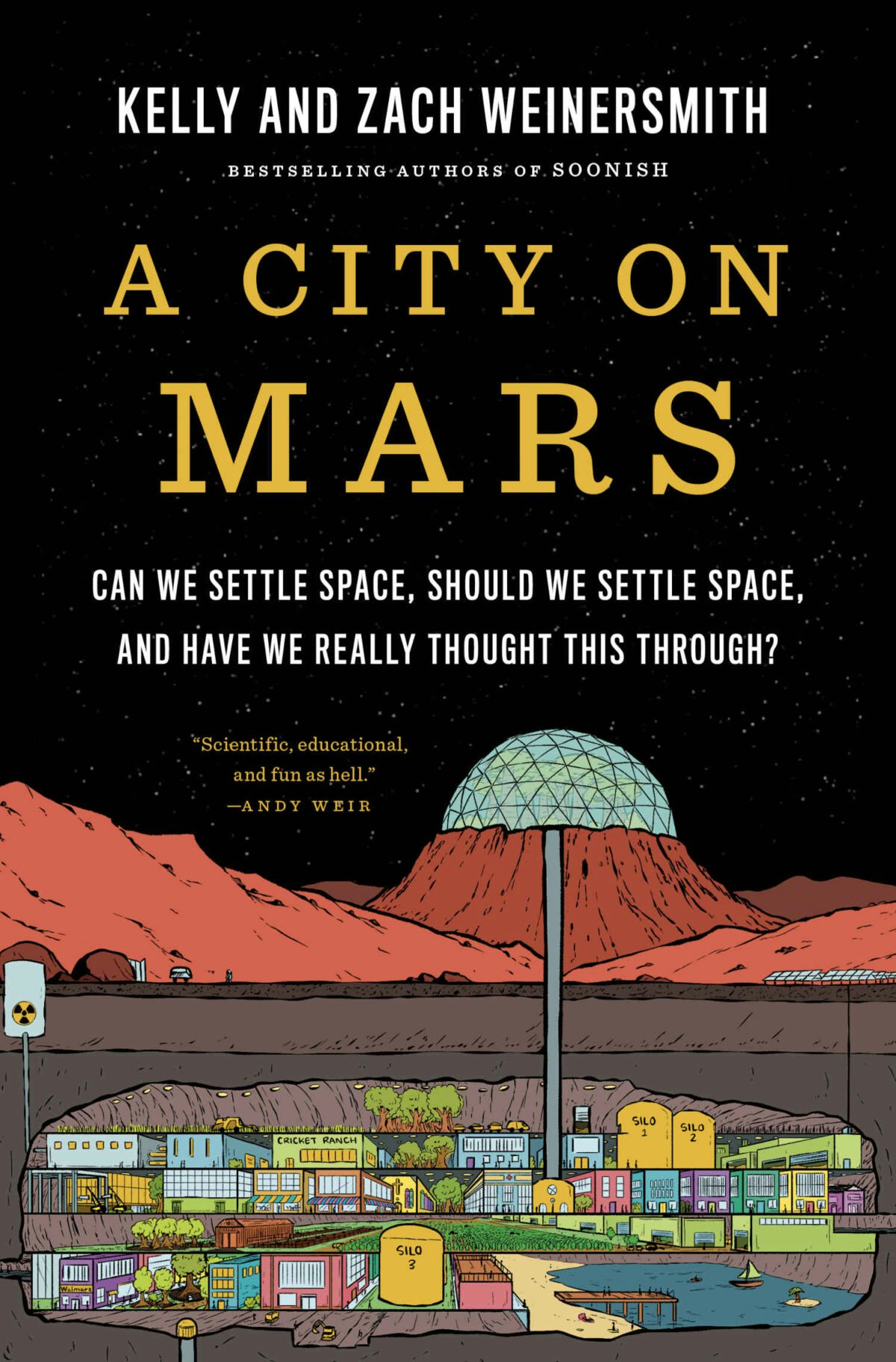

In their hilarious, highly informative, and cheeky book, “A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?”, Kelly and Zach Weinersmith inventory the challenges standing in the way of Zubrin-like visions for Mars settlement. The wife-and-husband team serves a strong, but never stern, counterargument to the visionaries promising that we’ll put humans on Mars in the very near future. “Think of this book as the straight-talking homesteader’s guide to the rest of the solar system,” they write.

Just as in their previous book, “Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That’ll Improve and/or Ruin Everything,” the authors — she’s a faculty member in the biosciences department at Rice University, and he’s a cartoonist — use humor and science to douse techno dreams with a dose of reality. “After a few years of researching space settlements, we began in secret to refer to ourselves as the ‘space bastards’ because we found we were more pessimistic than almost everyone in the space-settlement field,” they write. “We weren’t always this way. The data made us do it.”

While working on their deeply researched book, the Weinersmiths came to view sending people to Mars as a problem far more complicated and difficult than you’d know by listening to enthusiasts like Elon Musk or Robert Zubrin. It’s a challenge that “won’t be solved simply by ambitious fantasies or giant rockets.” Eventually, humans are likely to expand into space, the Weinersmiths write, but for now, “the discourse needs more realism — not in order to ruin everyone’s fun, but to provide guardrails against genuinely dangerous directions for planet Earth.”

Figuring out rocket technology and determining the power needs of a settlement or the available minerals on different planets or asteroids is the easy part. The bigger challenges, they argue, are “the big, open questions about things like medicine, reproduction, law, ecology, economics, sociology, and warfare.”

Take physiology. Although we now have a small number of astronauts who have lived at the International Space Station for long stretches, these astronauts have not had to deal with nearly as much radiation as would befall travelers far beyond. “With current knowledge, it’s hard to predict the effect of radiation on the body,” the Weinersmiths write, adding that the need to manage exposure to radiation is “one of the major factors that will shape human habitation designs off-world.”

For now, “the discourse needs more realism — not in order to ruin everyone’s fun, but to provide guardrails against genuinely dangerous directions for planet Earth.”

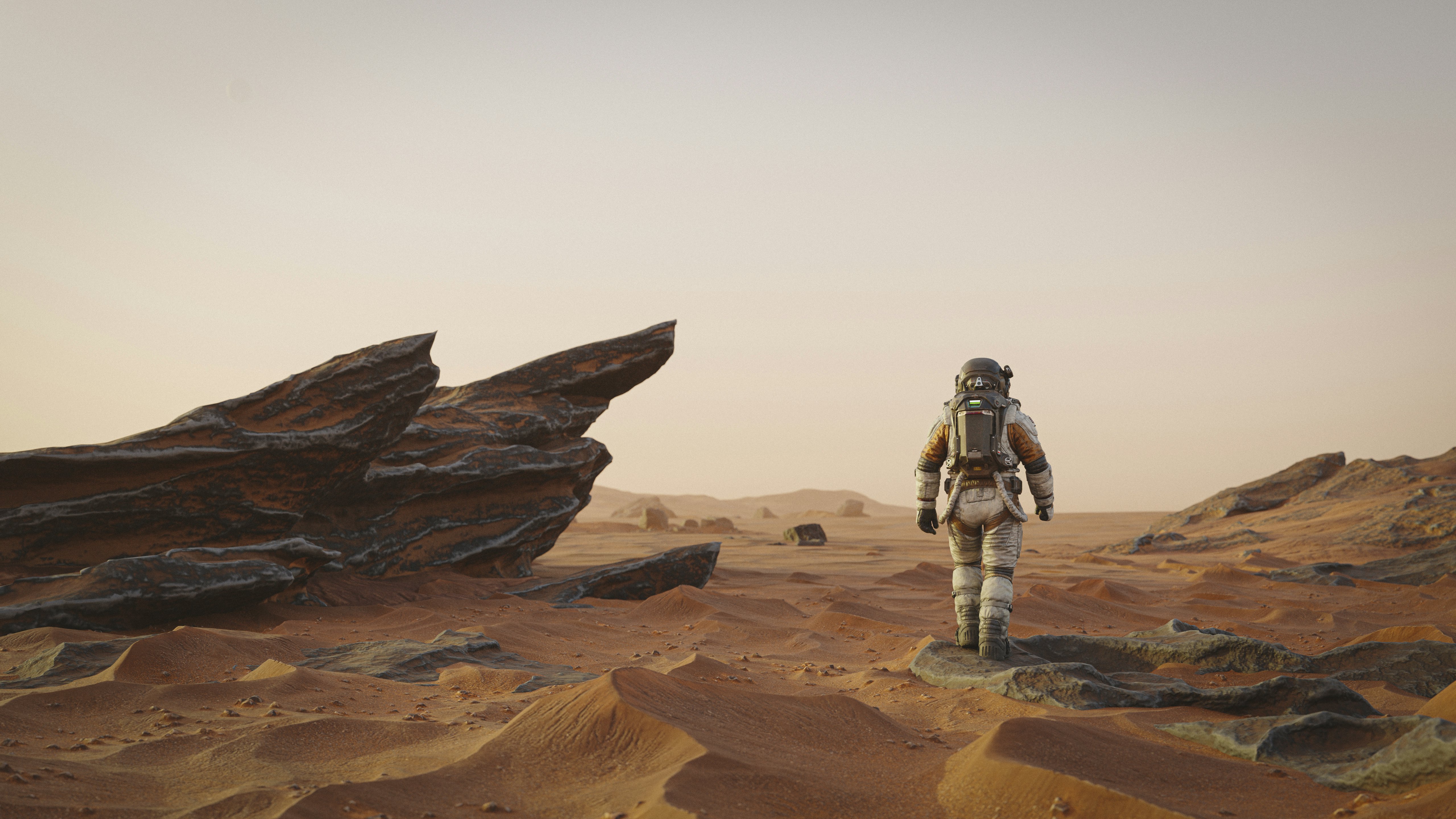

In the book, they recount architect Brent Sherwood dismissing those popular images of crystalline domes with sweeping views of space as “baseless.” As Sherwood wrote, “Such architecture would bake the inhabitants and their parklands in strong sunlight while poisoning them with space radiation at the same time.” Instead, some (short for “space homes”) are likely to be placed underground or, at the very least, surrounded by rocks to protect against radiation.

What’s more, if we’re going to sustain a population far away from Earth, we’ll need to figure out space sex, and the book spends several pages covering the debate over whether this activity has or has not happened yet. Although there’s been speculation that the 1992 space shuttle flight with married couple Mark Lee and Jan Davis would have provided a plausible opportunity for a successful “rendezvous and docking,” the authors write that there’s no evidence that this actually happened and there were five other crew members/potential witnesses aboard the flight that left little room for privacy.

If space travelers were somehow able to create a pregnancy, it would be no easy ride, the Weinersmiths write. We simply don’t know which, if any, part of the developmental process requires constant gravity, and the mother’s bones would be weakened in microgravity, which could make childbirth risky. If artificial gravity couldn’t be provided to the mother-to-be, an alternative might be a human-sized centrifuge to spin the pregnant person around. Such a device, called an “Apparatus for Facilitating the Birth of a Child by Centrifugal Force,” was patented in 1963, and Zach Weinersmith sketches a diagram of it that shows it to be just as bizarre as it sounds. In fact, his sketches often serve to demonstrate just how absurd some of the ideas promoted around space habitation really are.

What astronauts really long for when they’re away from home is, well, home. Anything that can help them recreate Earth far from home can provide some comfort. The book recalls how cosmonaut Anatoly Berezovoy loved to listen to cassette tapes with recordings of nature sounds like thunder, rain, and birdsongs during his 211-day spaceflight in 1982, saying, “We never grew tired of them.”

Living on Mars, which has no birds or rain, gets less than half the sunlight per area that Earth does, and is often plagued by dust storms that further blot out the sun, could be a soul-deadening experience.

The book spends several chapters covering space law and governance, which, in the Weinersmiths’ hands, is more interesting than it sounds. They explore the philosophical question of “who owns the universe?” and shoot down a common argument “that all law is pointless because if Elon Musk has a Mars settlement, who’s going to stop him?” (“One of your authors has a brother who makes this argument. His name is Marty, and he is wrong.”)

In fact, there are already frameworks that could guide space law, and the book covers them and their alternatives in detail. They use Earth-bound examples, like the breakup of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the governance of Antarctica, to explore how various governance scenarios might play out on other planets.

Mostly, though, the Weinersmiths use facts to debunk grand ideas about how fun and easy life will be on Mars. “An Earth with climate change and nuclear war and, like, zombies and werewolves is still a way better place than Mars,” they write.

They also run through a list of “Bad Arguments for Space Settlement,” which include “Space Will Save Humanity from Near-Term Calamity by Providing a New Home” and “Space Exploration Is a Natural Human Urge.” These detailed examinations of the stark realities regarding space travel and habitation serve as a foil to the breathlessly optimistic accounts that are so ubiquitous in popular media.

“An Earth with climate change and nuclear war and, like, zombies and werewolves is still a way better place than Mars.”

Despite often sounding like a couple of Debbie Downers, they somehow succeed at keeping the narrative upbeat and interesting. They do this with humor, frankness, and Zach’s fun sketches. Even as they shoot down a long list of space fantasies, they explore a lot of really interesting research and anecdotes (“Did you know the Colombian constitution asserts a claim to a specific region of space?”), so there’s rarely a dull moment.

The Weinersmiths view themselves not as “barriers on the road to progress” but as “guardrails” who want us to go to Mars as much as anybody. The trouble is that these self-professed science geeks (who watch late-night rocket launches with their kids) “just cannot convince ourselves that the usual arguments for space settlements are good.”

But they also assert, rather earnestly, that “If you hate our conclusions here, we have excellent news: we are not powerful people.”

This article was originally published on Undark by Christie Aschwanden. Read the original article here.