Welcome to the second Donald Trump era in Washington, although in practice, the first never really ended.

A majority of Republicans in the House Representatives voted to overturn the 2020 election results. Much of the party referred to him as “President Trump,” even after he left D.C.

Now back as president, Trump delivered a dark and heavily partisan inaugural address Monday. He used it to rehash plenty of his old scores, from arguing that he had been politically persecuted to promising that “the violent and unfair weaponization of the Justice Department and our government will end.”

Trump also used his opening remarks to tout the litany of various executive orders (EOs) that he plans to sign as president. Unsurprisingly, many of the EOs focus heavily on immigration, such as listing drug cartels as a terrorist organization, declaring a national emergency to surge troops at the U.S.-Mexico border and supposedly ending birthright citizenship under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Other EOs focus on rolling back protections for LGBTQ+ people, with an expected series of anti-trans orders. Trump announced in his speech that “the policy of the United States to recognize two sexes, male and female” and that “sexes that are not changeable, and they are grounded in fundamental and incontrovertible reality.”

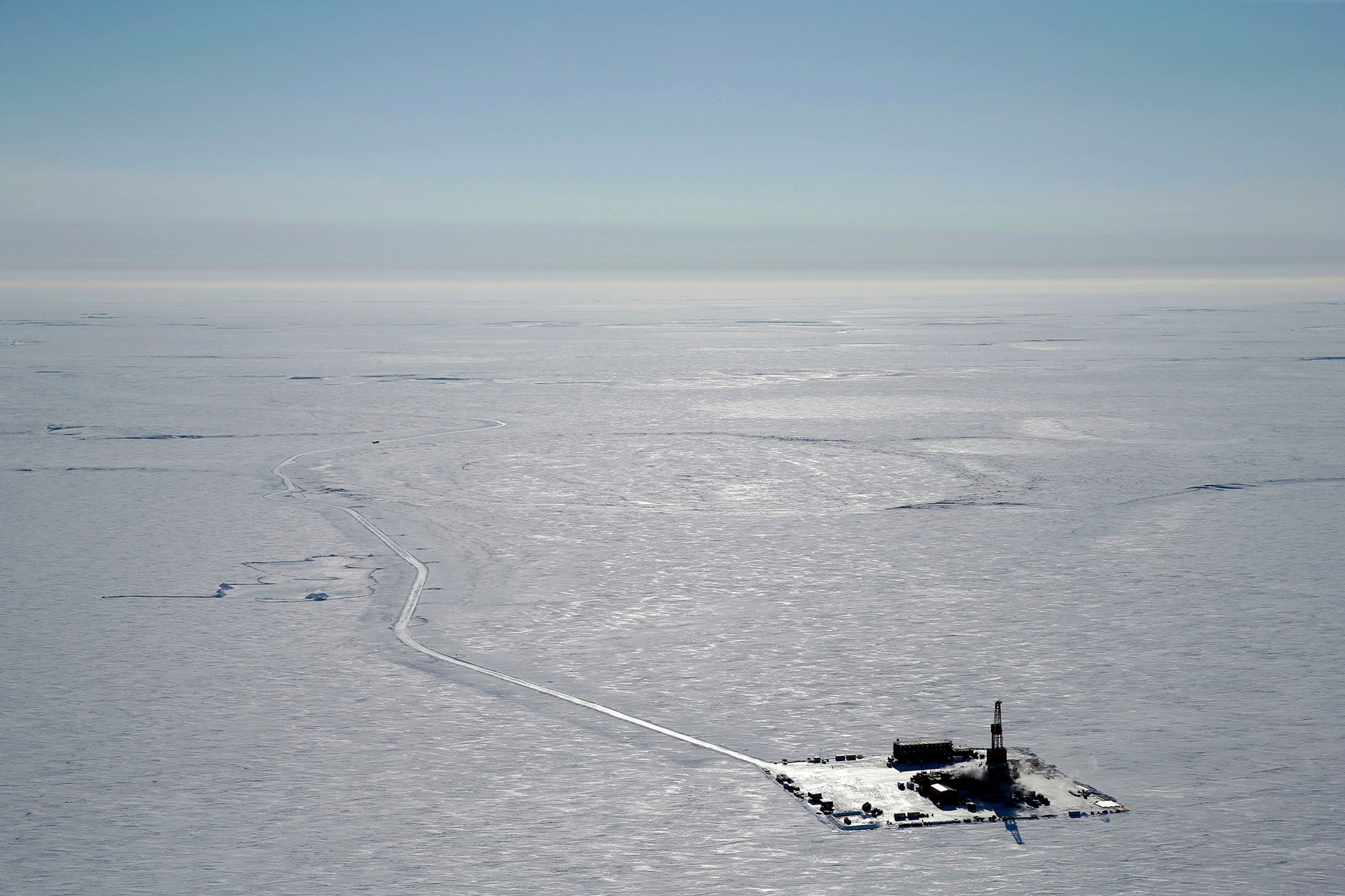

He also bragged about executive orders that will allow for oil drilling in regions such as Alaska, declaring “drill baby, drill.”

As president, Trump has plenty of authority to enact his policies — however, there are still some limits on the extent of what can be changed by executive order. Here are some areas where he might have trouble.

Immigration

The American public has largely moved to support more restrictive immigration policies since Trump took office in 2017. The Senate is slated to pass the Laken Riley Act, which would allow for immigration authorities to detain migrants arrested for theft, even if they are not convicted, after a number of Democrats joined Republicans to pass the legislation. The president will also be able to reinstate the “Remain in Mexico” policy from his previous administration, which forces migrants to stay in Mexico as their immigration cases are pending.

But this is where he faces difficulties. For one, while Trump wants to beef up spending at the U.S.-Mexico border, he will need to get money from Congress to do so. Republicans have only 218 seats in the House and a 53-seat majority in the Senate, meaning they have to deal with tight margins and get every Republican on board. The resignation of Michael Waltz from Congress to become his National Security Adviser, as well as Rep. Elise Stefanik to be U.S. ambassador to the United Nations gives Speaker Mike Johnson little latitude.

Trump pledged to completely shut down the border, resembling a pledge that former president Joe Biden made during the bipartisan border negotiations early last year. But Republicans largely rebuffed that bill because it would only come if crossings reached 5,000 a day.

Birthright citizenship

One of the most controversial of Trump’s planned executive orders is his declaration to end birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants.

Automatic citizenship for Americans born in the United States was adopted after the civil war, a hard fought-for right following previous laws that said anyone descended from enslaved people could not become citizens. Birthright citizenship has become a cornerstone of American identity, one of the few countries in the world to offer it and one of the only paths forward for many immigrants to ensure a better life for their children.

Almost certainly, civil rights groups will take this up with the courts as unconstitutional, since birthright citizenship is written into the 14th Amendment.

Even if the Supreme Court says this passes muster, it will inevitably be tied up in the legal system for longer than Trump wants.

Taxes

Trump faces a huge deadline at the end of the year as most of the tax cuts under the law that he signed in 2017 will expire. Republicans largely rebuffed a tax deal that included business investments and a new child tax credit last year because they hoped that Trump would come back and let them have a better negotiating deal. Since presidents share power with Congress when it comes to imposing tariffs, it will form a large part of Trump’s proposed economic agenda.

This part is largely beyond Trump’s control because it mostly requires that every Republican get on board in order to pass a bill via budget reconciliation, which allows for the majority to sidestep a filibuster as long as the legislation is germane to the federal budget. On top of that, Trump talked about an external revenue service to collect his proposed tariffs, which would require an act of Congress. It’s also not clear if tariffs would be able to make up for lost revenue from taxation.

Drilling

The president spoke about the need to increase energy production, although the words he used — “We will drill, baby, drill” — were a little more direct. As was the case in 2017, he will remove the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement, which will allow it to conduct more fossil fuel extraction.

The president has also hinted at rolling back an auto emissions regulation put in place by the Biden administration. He also planned on issuing a “national energy emergency” to authorize drilling in Alaska. The 2017 tax bill that he signed authorized drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and he would likely amp up drilling in the area, which has long been supported by Alaska Republicans.

But Trump would also face some major difficulties in increasing energy production. For one, the Biden administration ramped up oil production in the first part of his administration largely due to anxieties about oil prices. Now because of the war in Ukraine, oil production is at an all-time high.

Second, before he left office, Biden put in place a ban on offshore drilling for 625 million acres of the Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, this ban might be harder to lift without an act of Congress and many Republicans from coastal areas in Florida and South Carolina might object to having land near their area up for offshore drilling.

Renaming maps

Trump mentioned in his address that he wants to rename the Gulf of Mexico “the Gulf of America,” seemingly in large part because of the gas and drilling options available there. Or as Trump said earlier this month: “Because we do most of the work there, and it’s ours.”

This, again, would require an act of Congress. One of Trump’s biggest supporters, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, has legislation that could pass the House of Representatives but would likely not pass through the Senate. Even if it did pass and become law, there would be nothing to ensure that other countries had to ever use the name (remember freedom fries?).

Panama Canal

Trump has also been discussing retaking the Panama Canal, the famed shipping canal that allows trade between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. After controlling the canal for decades, the U.S. handed over full control to the Panamanian government in 1999.

This policy would not only require money to come from Congress but also require a negotiated agreement with Panama. Or at worst, the use of military force to seize it for the United States.

Not long after Trump’s address, Panama’s President José Raúl Mulino roundly rejected Trump’s call to seize the canal.

DOGE’s power

As for the proposed Department of Government Efficency, aka DOGE, which is supposedly spearheaded by Tesla CEO Elon Musk, there is evidence it might be in for a bumpy road. For one, it has already been sued four times. Second, the department does not have a clear mandate and is essentially an advisory committee rather than one with any authority. Third, presidential hopeful Vivek Ramaswamy was also supposed to be part of it, but announce on inauguration day that instead he was running for governor of Ohio.

And even putting all this aside, DOGE does not write the budget; the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate do and it could easily reject the recommendations of DOGE.

Even with the roadblocks, Trump has more wind at his back this time than during his first administration — in part because fewer Republicans like to cross him, and many agree with his extreme ideologies.

Democrats, still reeling after being battered badly during the 2024 election, might be inclined to go along with at least some of his policies. But that doesn’t mean it’ll all be smooth sailing.