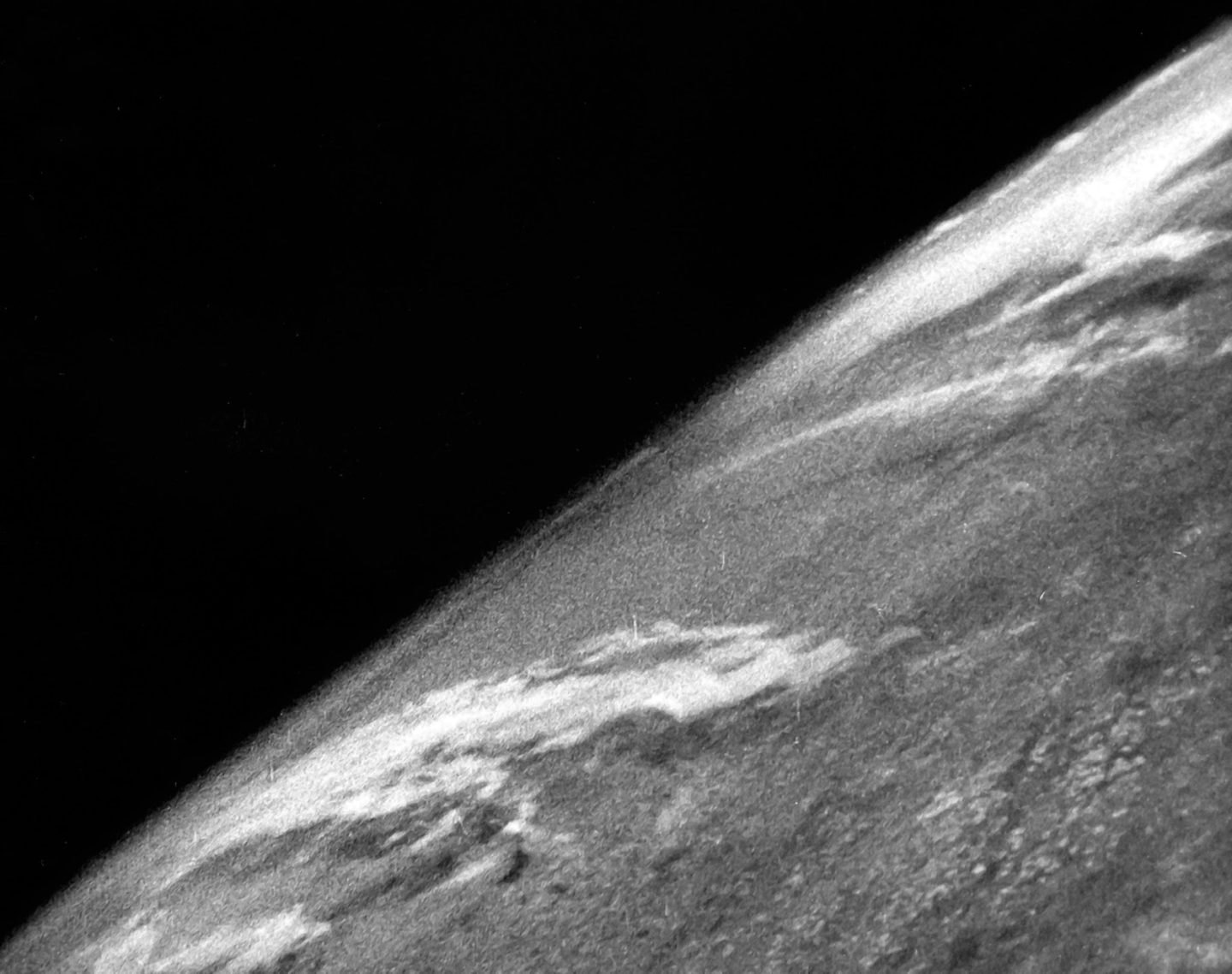

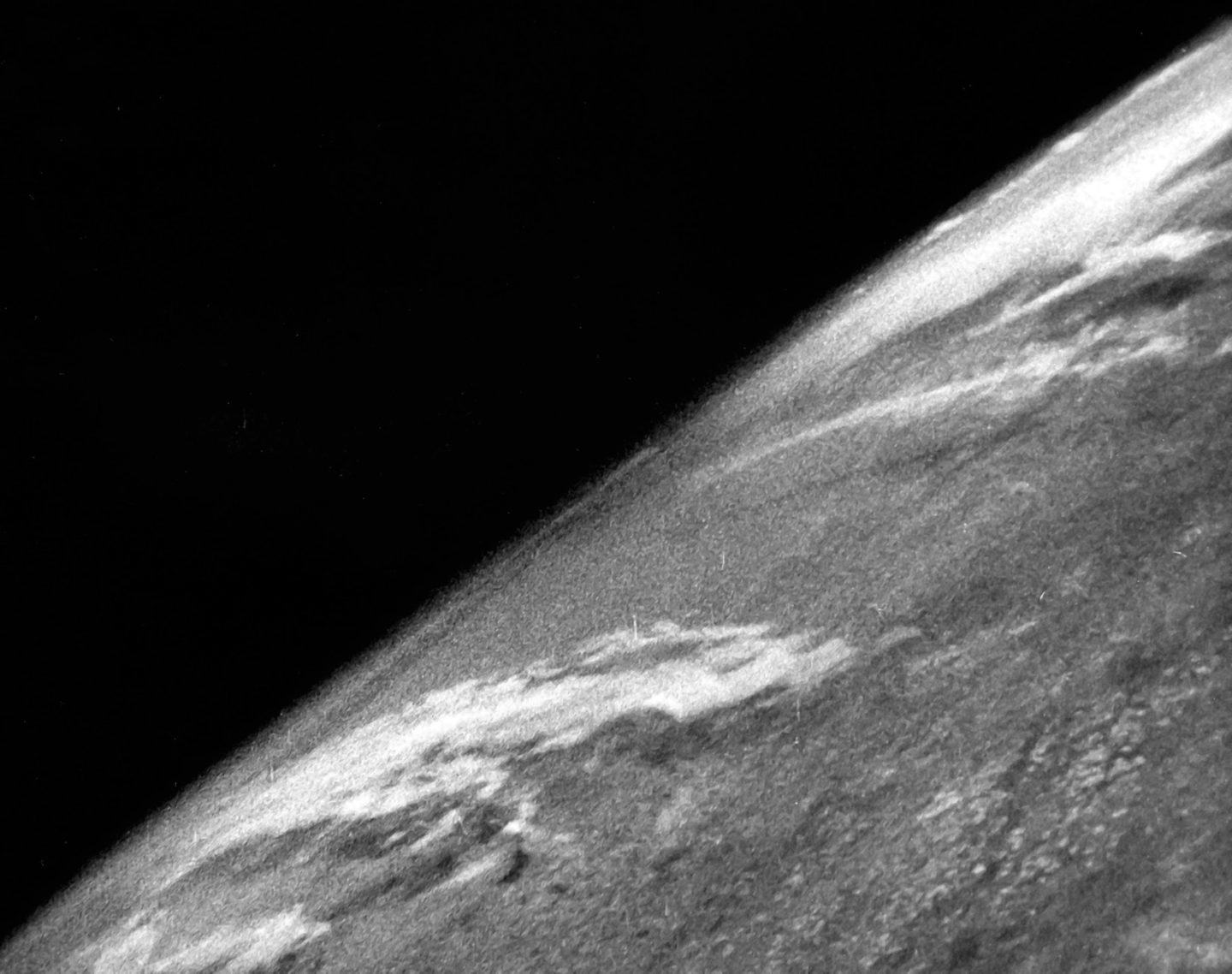

By the standards of today, it’s just a grainy black and white photo.

It takes a minute to make out what are smooth white cloud formations floating above the fuzzy greyscale Earth, a swirl of monochrome set against the blackness of space.

NASA astronauts have taken more than 900,000 images from space. But 75 years ago — before Scott Kelly was given a Nikon D4, and before the famous “Blue Marble” full view of Earth — there was this. The very first photograph of Earth from space.

It was taken on October 24, 1946. And while the more refined images of Earth would later eclipse it in popular memory, it was a big deal at the time.

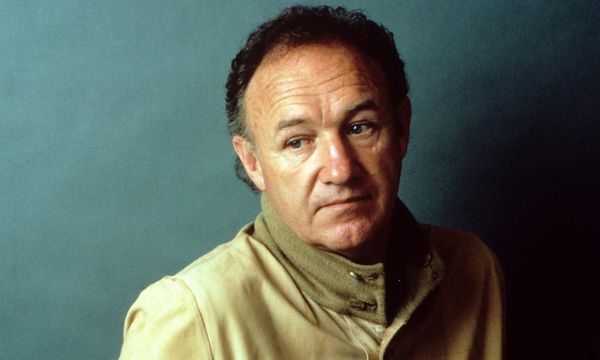

“For 1946, it was an astounding accomplishment,” Michael Neufeld, Senior Curator in the Department of Space History at the National Air and Space Museum, tells Inverse. “It was a news item.”

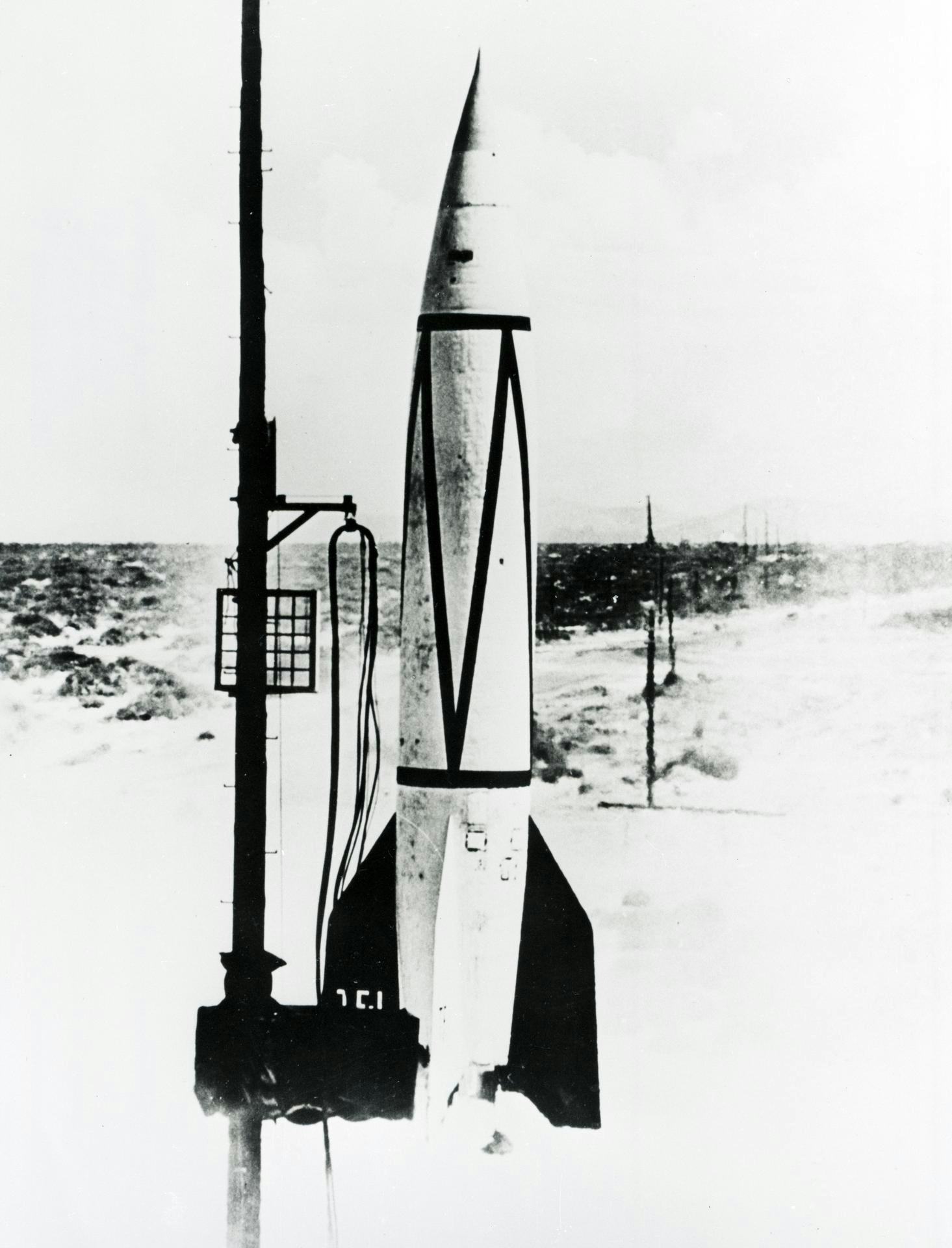

How the photo was taken was a pretty big deal too: It was shot with a 35mm film camera housed between the fuel tanks of a captured Nazi V-2 rocket launched from White Sands Missile Range.

It was a single rocket launch from the New Mexican desert that simultaneously jump-started the Cold War, the Space Race, and experimental space sciences.

How Nazi rockets led to NASA rockets

American scientists and engineers were familiar with the concept of rockets, with Robert Goddard famously flying the world’s first liquid-fueled rockets in the 1920s.

But with the collapse of the Nazi regime at the close of World War II, the Allies discovered just how much further the Germans had been able to take the technology with their V-2 rocket.

“It had been a failure as a weapon because it was a very expensive way to drop a 1-ton bomb on an enemy city,” Neufeld says. But it was also “obviously a technological breakthrough that could herald a new age of either space vehicle or ballistic missiles,” he adds.

Naturally, the United States — and the Soviet Union — captured as many V-2s as they could find and began studying them, flying them, and aiming to improve them.

“The V-2 was only the harbinger of what was possible.”

National Air and Space Museum Curator Emeritus David DeVorkin tells Inverse that “the early efforts on the American side were to first build a device that could protect us from something like a V-2 and then build our own.”

“The V-2 was only the harbinger of what was possible,” DeVorkin says.

And so the U.S. Army — working with General Electric and the U.S. Navy supported Applied Physics Laboratory and Naval Research Laboratory — began packing V-2s with scientific instruments and cameras and lofting the rockets into the upper atmosphere above New Mexico.

It did not always go well.

“One of the big challenges was, at that point, the U.S. had no way to recover a payload,” Neufeld says.

Developing parachutes to work with the German-made rockets would take time and money the engineers didn’t have, so “what they did on the early V-2s is essentially put things in armored casings and hope that it would survive being smashed into the ground at several 100 miles per hour,” Neufeld explains.

There was no rocket telemetry in the early days, and certainly no GPS beacon, so even if a camera or instrument survived the fall, it could take a while to find the crater.

“You’d have radar tracking, which gives you an approximate location of where the impact was, but that's it,” Neufeld says. “They'd have to send people out in Jeeps in the desert and say, ‘look for a hole roughly over there.’”

The first photo of Earth from space

The 12th and 13th V-2 rocket launches from White Sands were relative successes, however.

The 12th launch, on October 10, 1946, became the first space-science experiment conducted via rocket. A solar spectrograph recorded the absorption pattern of ultraviolet light in the upper atmosphere.

The 13th launch, on October 24, carried the film camera rigged — using parts from a B-29 bomber’s fire control system — to take time-lapse photos from the rocket’s midsection during its flight to an altitude of 65 miles.

The camera worked beautifully, and even managed to survive the fall, Dvorkin notes in his book on the project. “A few hours after crashing,” he writes, “the camera was found at the impact site ‘in almost perfect condition’ although a lens had been lost.”

Unlike later Cold War aerospace development programs, such as Chuck Yeager’s 1947 flight to break the sound barrier, the V-2 launches were not kept secret, but widely publicized.

By November, images from the October 24 flight taken at various altitudes were released to the press. The Los Angeles Examiner, DeVorkin writes, ran them with the headline, “You’re on a V-2 Rocket 65 Miles Up!”

The Trans-Lux movie newsreel service called the images the “most sensational newsreel images of all time.”

The V-2 images were not the first high-altitude photographs the public had seen showing the curvature of the Earth — those had come from the crew of the Explorer II high altitude balloon, a mission funded by the National Geographic Society that reached an altitude of more than 13 miles in 1935.

But the V-2 images were taken from five times that height, and clearly showed the blackness of space. They were taken in space from an altitude of 65 miles and struck a chord.

“Just like the Hubble images are the highlights that really excite people,” DeVorkin says, “here you could see the Earth and you could see vast parts of the Earth.”

The legacy of V-2 rocket No. 13

But it wasn’t just the popular imagination that was fired up by the V-2 images. The military saw in them the potential for high-altitude optical reconnaissance.

One of the Naval Research Laboratory engineers working on the V-2s, Thor A. Bergstralh, even began thinking about how useful it would be to have a rocket with a camera that didn’t come down, DeVorkin says — a satellite.

“It says, ‘we now have a technology that can actually send something up there.’”

The V-2 further bolstered the voices of scientists and engineers who discussed space travel in the 1920s and 1930s, when it was assumed to be a far-future endeavor.

“The V-2 legitimizes as a lot of this,” Neufeld says. “It says, ‘we now have a technology that can actually send something up there.’”

Meanwhile, the work of Bergstralh and other scientists and engineers, including James Van Allen of the eponymous gradation belts, not only yielded space science discoveries but helped develop the sort of rocket and missile guidance systems that would be necessary for both the nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) of the Cold War and the launch vehicles of the Space Race.

“Those were always the two sides of the rocket and still are the two sides of the rocket,” Neufeld says. “I mean, right now we're hearing daily news on either China or North Korean ballistic missile programs and hypersonic missile programs.”

Today as then, the twin sides of the rocket accelerate each other.