In 2024, a 70-year-old international film titan finally won his first Oscar. After starring in 38 movies, the King of All Monsters, Godzilla himself, took home the most famous gold statuette in Hollywood. The franchise may have just won its first Academy Award thanks to Godzilla Minus One, but its legacy as a smart franchise following a terrifying creature was baked into its 1954 introduction. The series has since branched off into decades of high camp, but with a widely lauded Academy Award alongside a big-budget popular American franchise, a widely-watched Netflix animated film trilogy, and newly terrorizing Japanese visions, its international cultural longevity has never left a larger footprint.

Conceived as an embodiment of the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the original Godzilla was an angry, powerful, vengeful creature that devastated Japan. Awakened by an atomic bomb, its skin is covered in keloid scars resembling those of the survivors of nuclear blasts. The beast attacked Japan with radioactive breath as residents fled in terror. The creature was a living metaphor, providing a venue to express and explore real-life traumas and fears, as well as to examine bureaucratic apathy and ineptitude.

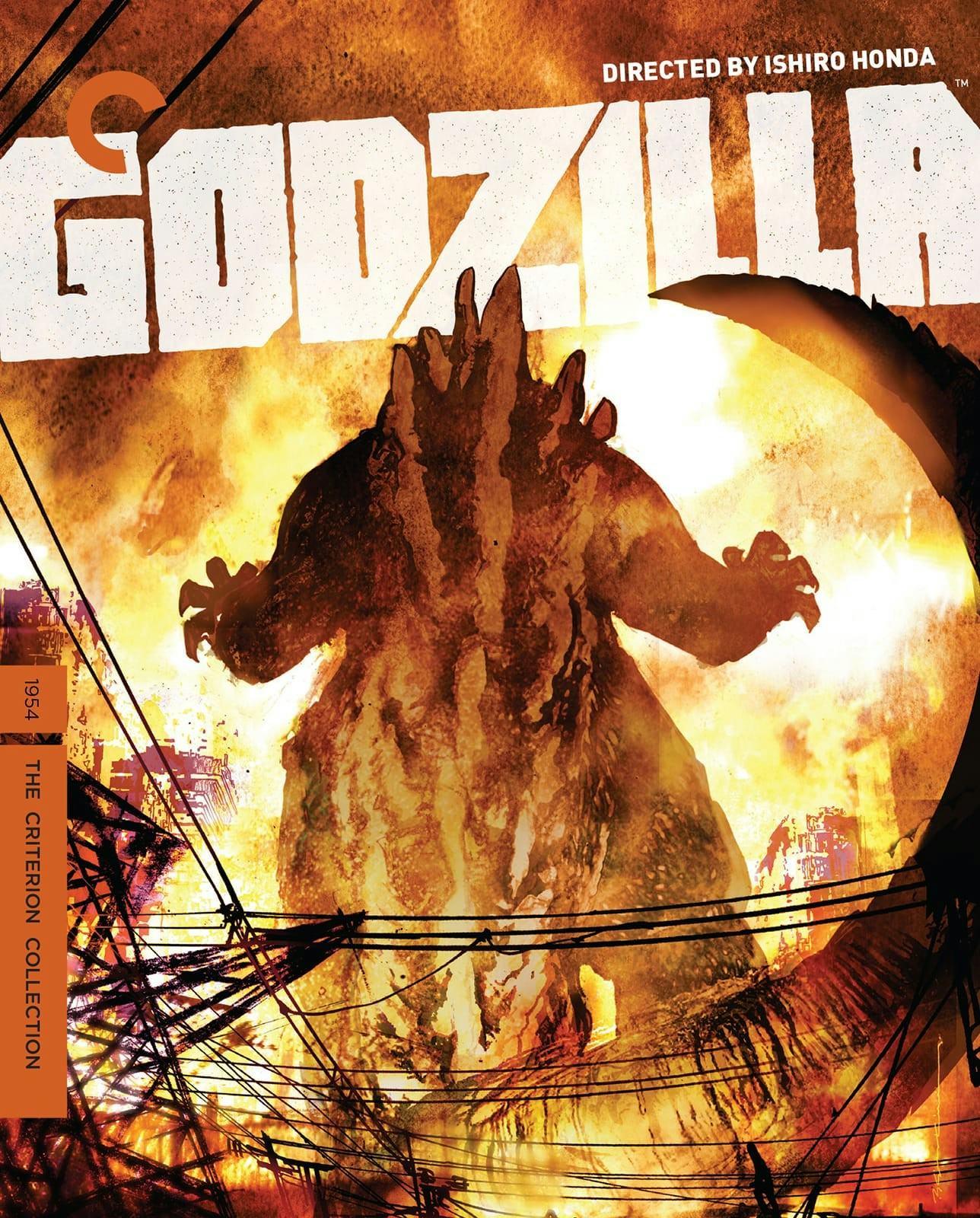

With the release of a glorious new, digitally restored Criterion Collection version of the 1954 classic on 4K Ultra HD and Blu-ray, there’s never been a better time to revisit the original Godzilla and the unstoppable franchise it launched.

Starting with the immediate 1955 sequel Godzilla Raids Again, the series branched off into decades of high camp, Godzilla often taking a heroic role against more threatening or antagonistic monsters like King Ghidorah or Destroyah. For Americans, receiving the wildly different (and inferior) 1956 Godzilla, King of the Monsters! recut of the original that removed much of its political sting (including a scene in which train passengers link Hiroshima to Godzilla), the frightening original film was internationally reduced to a fun, dumb monster movie — and American audiences were ready for it.

While the 1954 original was a proper horror film, that isn’t to say its campier sequels weren’t great or intelligent in their own right. The series continued to use the kaiju to represent various ills and issues. Hedorah serves as an analogous representation of pollution in 1971’s Godzilla vs. Hedorah, while in 1989’s Godzilla vs. Biollante, Biollante could be read as a warning against human genetic manipulation. The films also regularly carry themes of ecological relationships, the callousness of the United States, and so on, all wrapped in the package of super-powered monster fights.

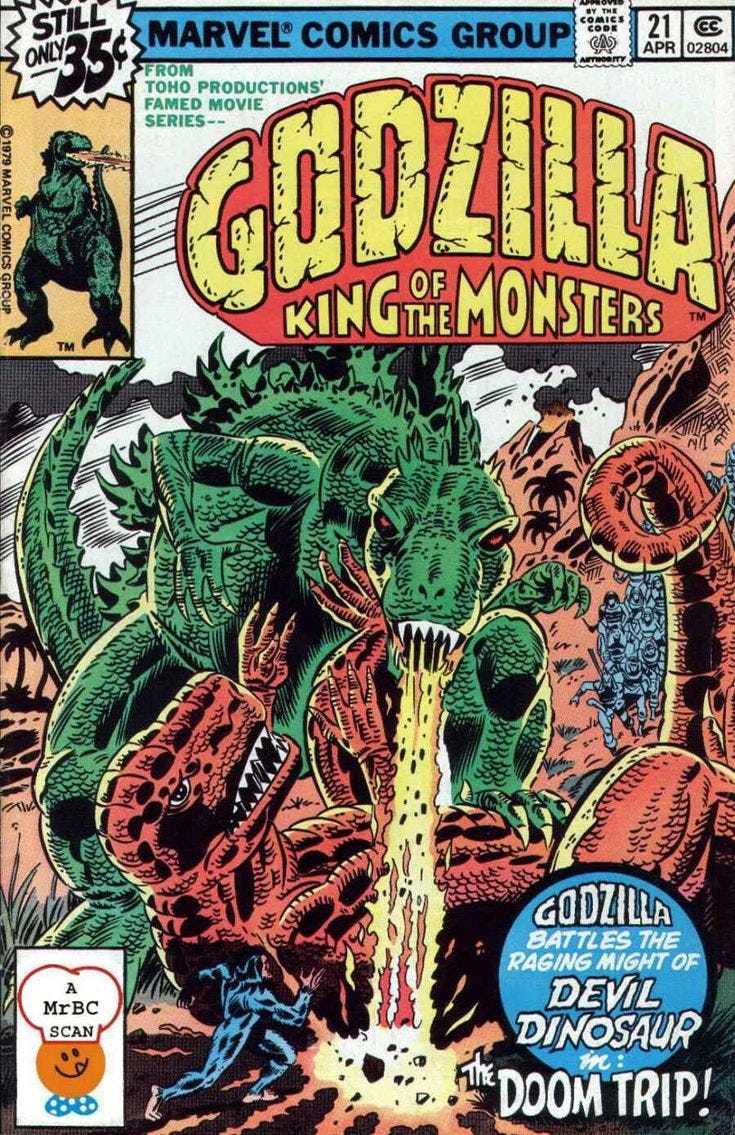

Over time, Godzilla retained a dedicated international fanbase and fueled a multi-media empire that included comics (like Marvel’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters crossover from 1977 to 1979) and video games going back to the 1983 Commodore 64 Godzilla. When 1998’s American Godzilla hit theaters, it was mildly profitable but so ill-received that 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars introduced an iguana-like kaiju dubbed Zilla resembling the 1998 iteration, branding that Toho has maintained to scrub the 1998 iteration from existence.

Eventually, Legendary Pictures secured the rights to produce 2014’s Godzilla, directly inspired by the 1954 original and sparking the Legendary Monsterverse. The Monsterverse films branded kaiju as Titans, powerful entities from the Hollow Earth who ruled in an older, more radioactive era. In the Monsterverse, kaiju are treated as a sort of embodiment of Gaia theory, maintaining the natural order and regenerating the ecosystem (as explored in 2019’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters). Meanwhile, 2016’s Shin Godzilla restarted the Toho features while returning to horror, and Godzilla Minus One utilized Big G to explore survivor’s guilt and defend the value of individual human life.

In many ways, Godzilla has rarely had greater international cultural prominence. Godzilla Minus One was sufficiently popular in the United States that Toho kept extending its theatrical window, and its history-making Academy Award for Best Visual Effects is wildly appropriate given that Godzilla co-creator Eiji Tsuburaya was an effects wizard, pioneering the innovative use of miniatures and “suitimation” techniques that characterized the franchise. Meanwhile, the Monsterverse moved on to its sixth film with two series under its belt. Godzilla’s massive global footprint has never been larger.

On the one hand, the Godzilla franchise has proven itself an extremely adaptable franchise. You’ll never find a comedic James Bond film or a horror entry in the Fast and the Furious franchise, but the Godzilla films have ranged from horror to goofy exercises in high camp (1967’s Son of Godzilla or Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire), to the Monsterverse’s sci-fi-actioners or Godzilla Minus One’s dramatic exploration of the aftermath of World War II. Similarly, the symbolic adaptability of cinematic creatures has allowed the franchise to explore topics as diverse as the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Japan, survivor’s guilt, environmental devastation, ecology, and even adoptive parenthood. There’s a Godzilla for everyone and every topic.

As chronicled in books like Matt Kaplan’s The Science of Monsters and Stephen T. Asma’s On Monsters, stories of monsters and the monstrous have long been used to represent primal, incomprehensible forces and warnings against moral and social transgressions. Cinema history is similarly filled with warnings against scientific hubris (Frankenstein, Jurassic Park), political ineptitude (Jaws, The Host), the dangers of the cosmos (Alien, The Thing), and almost any other theme imaginable. The Godzilla franchise ties specifically into that sense of awe and wonder that populates our worldwide mythological tapestry and reflects our species’ most primal fears and instincts. That timelessness and the franchise’s easy adaptability helped a 1954 Japanese classic become an international multimedia franchise, more popular than ever after 70 years.