If a game is no longer for sale, unless it's exceedingly popular and recent, it often fades from the broader cultural consciousness.

But learning more about the medium’s history can allow us to better parse and understand the patterns that persist within that history, and how they shape the present moment.

The Portopia Serial Murder Case is a game that we don’t hear about much in the West. Created by Yuji Horii, who would go on to develop the hugely influential Dragon Quest role-playing series, this pioneering narrative adventure was first released in 1983 for the NEC PC-6001 computer and later ported to the Famicom (Japan’s name for the NES) in 1985.

Portopia was far ahead of its time in its experimentation with narrative devices and mechanics that have become standardized and widespread today. If you have searched through the crime scenes of Ace Attorney or questioned the residents of Danganronpa, you will likely already be familiar with foundational elements of the game’s design.

Yet despite its enduring influence, Portopia has never been released outside Japan. Instead, fan translators — specifically DvD Translations, Harmony7, and Shiroi — have endeavored to make the game accessible to English speakers. If you play Portopia in English, you’re not just experiencing a young Yuji Horii’s passion project, but over a decade of fan translation efforts as well.

A massive influence

Visual novels have long been a niche genre outside Japan. But the last twenty years have seen the story-heavy format spike in popularity internationally, thanks to series such as Ace Attorney, Danganronpa, and Zero Escape. However, much of the genre’s rich history before the 1990s remains relatively unknown — and woefully underappreciated — in the West.

Portopia was one of the first titles Enix ever released, with only 1983’s puzzle platformer Door Door preceding it. It was also one of the first games that Horii wrote and designed himself. (His very first game was 1983’s Love Match Tennis, which won an Enix-sponsored contest for amateur developers). Unlike the RPG series he’s best known for, Portopia was the first game to utilize point-and-click adventure mechanics — even before Sierra Online’s Kings Quest implemented them a year later.

Many prominent Japanese developers have cited Portopia as inspiration for their works, including the visionary game director Hideo Kojima, creator of Metal Gear Solid series. Kojima said in a 1999 interview with Nice Games (via shmupulations) that Horii’s game changed his ideas about what games could be.

“What made up my mind to get into this industry myself was Super Mario Bros. and The Portopia Serial Murder Case. They weren’t the ‘bleep bloop’ games of old; these games had their own worlds and stories. I felt a certain authorial quality in them,” he explained.

Kojima adds that Portopia’s worldbuilding, story, and dialogue convinced him that games could have “cinematic nuances,” a fascination that’s still evident in his work all the way up to Déath Stranding. Kojima and his desire to replicate that sense of “complete control” of the narrative in his own work was a major inspiration for Policenauts and Snatcher. He even hid parts of Portopia’s code inside Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain.

“They weren’t the ‘bleep bloop’ games of old.”

Alongside Kojima, other renowned game creators have noted Portopia’s influence as well. Eiji Aonuma, known for directing The Legend of Zelda series, notes that alongside Dragon Quest, Portopia was one of the first games that he ever played. Other notable figures who have cited Portopia as an early inspiration include Yakuza and Judgement series creator Toshihiro Nagoshi, and 428: Shibuya Scramble director Jiro Ishii.

Enduring ambitions

Despite Portopia’s ongoing influence among Japanese game developers, the game remains relatively little known in the West, though a number of dedicated enthusiasts have worked to preserve and raise awareness of the game’s legacy internationally. Since 2004, fan translation group DvD Translations has localized two versions of the game and resurfaced scores of articles and archival materials related to its history.

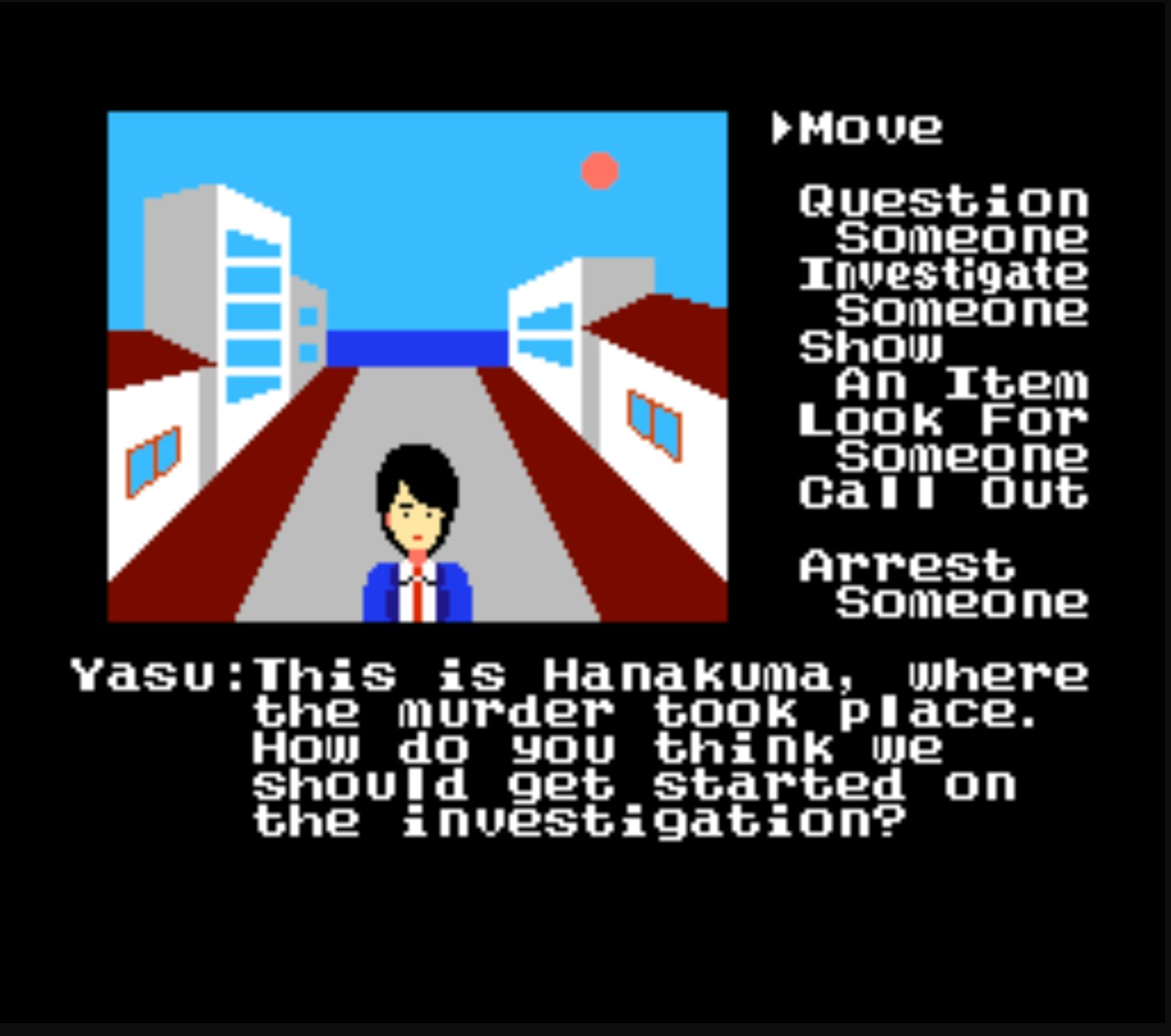

Portopia follows two detectives attempting to solve the murder of banking CEO Kouzou Yamakawa, taking them to locations inspired by the real-life Kobe waterfront. The game begins in the suburb of Hanakuma, but then the player is free to explore all available locations — Kobe Harbor, Shinkaichi, Portopia, the local police station, and the mansion where the murder took place — in any order they see fit.

Unlike other mystery narratives, we don’t even know the name of the protagonist — only that of his sidekick, Yasuhiko Mano, often referred to as Yasu. This doesn’t stop the detective duo from having a lot of personality and wit, though.

Throughout the game, many of the player’s actions can be bounced off Yasu for comedic effect. For instance, if the protagonist requests Yasu to look for someone who isn’t present he meets with silence and responds, "No answer. So lonely….” If the player attempts to hit certain objects in the environment, Yasuhiko will respond with “Tap tap tap. Hey Boss, what are you hoping to find with all that tapping?”

Unlike other early adventure titles such as 1987’s Maniac Mansion, there is no fail state or game over in Portopia, and much of the experience consists of wandering down streets with no clue where to go next. (In my own playthrough, I imagined myself as a detective who has followed all the leads and is taking a walk to blow off some steam.) You can send Yasu to ask around with the locals to see what’s been up, call up a lead, or maybe pop into a bar where a suspect has seen.

It’s often difficult to figure out where the game wants you to look in each space, and like many older adventure games, Portopia seems to expect you will pixel hunt. Yet each room isn’t just a puzzle to solve, but a space with little things to find. Then something clicks, and the mystery continues on.

Portopia’s beauty shines brightest in these quiet, aimless moments. Despite its rudimentary aesthetics, the game manages to evocatively recreate the real-world spaces that inspired it. The streets of Hanakuma stretch into the ocean in the background. Kyoto is covered in large rolling green hills. The water of Kobe Harbor is only given detail by the squiggles indicating motion. A ferris wheel and single building sit side by side in the background.

It’s like looking at the ultrasound of a genre in utero.

Time to remember

While ahead of its time in many respects, Portopia is reined in by the hardware limitations of the early 1980s. The entire game is composed of still images and all of the noises are essentially harsh beeps. Nevertheless, the ambition behind Horii’s early dream of what games could be was unprecedented.

In a 1987 interview with BEEP (via shmupulations), Horii said he initially wanted Portopia to feature a fully sentient AI that would allow the mystery to unravel through conversation.

“The first computer I ever bought was an NEC PC-6001, and I very quickly learned BASIC after that. I thought programming was really fun and interesting. Then I started to get more ambitious, and I thought I could make the computer converse with you if I entered enough data… but I soon learned that kind of thing wasn’t possible, so I quit. After that, I figured that if I couldn’t make the computer create its own speech, then I’d try creating dialogue for the computer beforehand and just make it talk with you that way.”

When Horii first started developing Portopia, adventure games didn’t have much (if any) dialogue. Instead, they mostly focused on describing locations and having the player choose commands to move and interact with their environment.

The original version of Portopia asked the player to input all commands via keyboard. However, the Famicom port released in 1985 included a new interface called “command style.” (Horii had first used this in 1984’s Okhotsk ni Kiyu: Hokkaido Rensa Satsujin Jiken, the spiritual successor to Portopia.) Command style presents the player’s options on a side menu, instead of requiring a keyboard. The format became a staple in Japanese adventure games and inspired countless command-style games, including the Famicom Detective Club titles that were recently remade for the Switch.

“Then I started to get more ambitious.”

The Portopia Serial Murders deserves greater esteem and wider remembrance for its groundbreaking ideas and impact on the medium. While the game certainly shows its age, a single playthrough is an enjoyable reminder of how far the genre has come since.

We are reaching a point in time where visual novels are more accessible than ever, with some of the most seminal titles in the genre made available via fan or publisher translations very recently. However, for the longest time the genre has continued to be made a joke by Western audiences or only acknowledged when reaching a popular status. They need not remain as niche works left for enthusiasts to play but games which we acknowledge and celebrate for their contributions to what we play today.