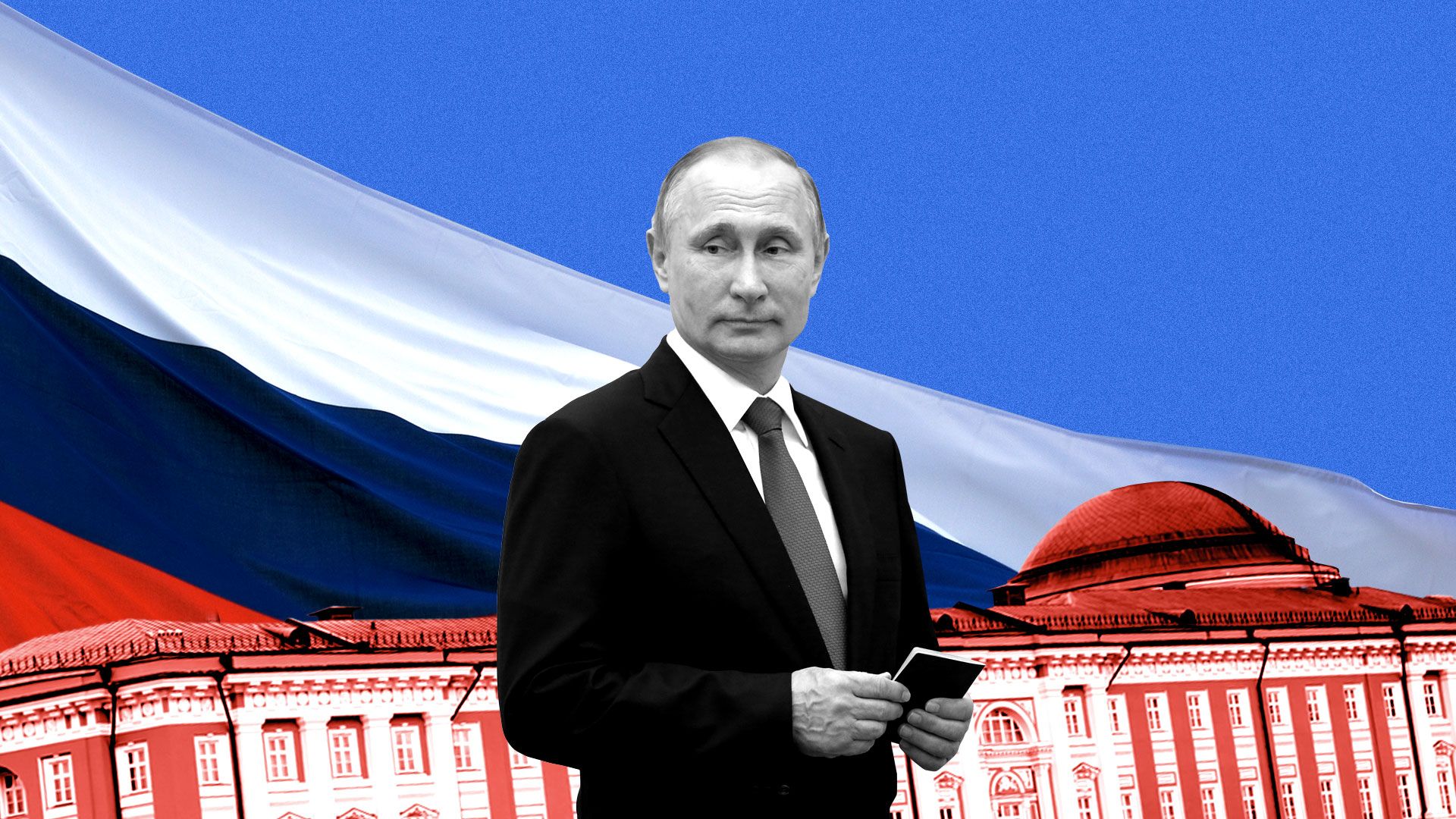

Twenty years ago today, on New Year's Eve 1999, a political newcomer and former KGB operative named Vladimir Putin suddenly assumed the Russian presidency.

Part 1 of our "20 Years of Putin" special report focuses on his rise, his early years and his escalating antagonism with the West. It's based on conversations with Mikhail Khodorkovsky — the oligarch whose imprisonment in 2003 revealed Putin's ruthlessness to the world — three former U.S. ambassadors to Moscow, leading experts and former chiefs of the Pentagon and CIA. Read part 2.

A "talented recruiter" rises to power

There aren’t many people who could have stood between Vladimir Putin and the Russian presidency two decades ago. Mikhail Khodorkovsky was one of them.

The big picture: Once Russia’s richest man, Khodorkovsky and a handful of other powerful oligarchs loomed large in the chaotic decade that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union.

- His imprisonment in 2003 shocked the world and was the moment many gave up on the illusion of Putin as a Westward-looking modernizer.

- Since being freed six years ago, Russia’s most-famous dissident-in-exile tells Axios his mission is now to prepare Russia for life after Putin.

“I could have made it more complicated for him to reach power,” Khodorkovsky acknowledges with a slight shrug, glancing up at the high ceiling of the London townhouse from which he runs his Open Russia foundation. “But this would mean giving up everything else and just doing this job of making obstacles for him.”

- Besides, Khodorkovsky says, he trusted then-President Boris Yeltsin, and Yeltsin had great faith in his hand-picked successor.

Like nearly all of those interviewed for this special report, Khodorkovsky saw something in Putin 20 years ago that was either never there or has long since evaporated.

- “Of course, I was aware of Putin being from the KGB, and I was aware of his business in St. Petersburg,” Khodorkovsky continues, referring to Putin’s time working for Mayor Anatoly Sobchak. "That did not inspire me at all.”

- But when Khodorkovsky met Putin, he became convinced this was “a very, very, democratic person,” intent on reform and Westernization.

Between the lines: Khodorkovsky says he hadn't realized what a "talented recruiter" Putin was.

- "He’s able to be in your eyes what you want him to be," he continues. "It’s unfortunate, but the only thing I can say in my defense is that I wasn’t the only person who was deceived by him.”

Khodorkovsky ran afoul of Putin when, as CEO of oil giant Yukos, he pushed for greater transparency in Russian business. At first, he saw Putin as a potential ally.

- “I had the impression at that time that the president is not taking any bribes,” he says. “People under him can take money, but he doesn’t need to. I was mistaken.”

- Putin saw Khodorkovsky as "one of the leaders of the alternative path," he says. "So he decided to use me as an example to frighten everyone else. And he succeeded.”

Out of the shadows: From KGB to Kremlin

Putin was a mid-level KGB officer in Dresden, East Germany, when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

Weeks later, in the tumult that preceded the collapse of the USSR, crowds stormed the local secret police headquarters and Putin spent a tense night waiting for orders from Moscow that never came.

- He returned to Russia and became a close aide first to Sobchak in St. Petersburg and later to Yeltsin in Moscow.

- He was little noticed in Russia or abroad until Yeltsin appointed him director of the KGB's successor, the FSB, in 1998.

- A year later, he was prime minister. Four months after that — on New Year's Eve, 1999 — Yeltsin resigned, and Putin's rise was complete.

Michael McFaul, who served as U.S. ambassador to Russia under Barack Obama, crossed paths with Putin in St. Petersburg in the 1990s.

- "My strongest memory was that he made no memory," McFaul says. “He made virtually no impression back then.”

- "I met Putin several times without noticing him," says Anders Åslund, a Swedish economist who worked as an economic adviser in Russia in the early 1990s. "He was very much a person who did not want to be seen."

- Nearly all accounts of Putin at that time describe a man who absorbed much and said little.

Behind the scenes: Former Defense Secretary Ash Carter was in several meetings with top Russian officials in the mid-1990s, when he was an assistant secretary of defense.

- Across the table was Yeltsin. Behind him, taking notes, was Putin.

- “We had an intelligence assessment of him then that is not that different than the assessment you’d give now," Carter says. "His first loyalty was to the security services, who deplored the end of the Soviet Union."

Consolidating control: A man of action

Even Putin's critics acknowledge that he has accomplished three central objectives: building a strong Russian state, re-establishing Russia as a global power, and maintaining his own grip on power.

Flashback: "I frankly lived the whole decade of the 1990s with the fear of a Russian civil war at the back of my mind," recalls Dmitri Trenin, a former Russian army officer and now director of Carnegie Moscow. "Right up until Putin’s coming to power."

- “Russia was turning into a confederacy at best in the 1990s and people were speculating about the world without Russia ... that this big country that thought of itself as a great power with a global impact would cease to exist.”

- “That was the domestic and international setting at the time when Putin was given the job of prime minister and then of president.”

"He immediately energized the entire country," Trenin says.

- "They saw an infirm Yeltsin, ringed by a bunch of oligarchs, having ministers who were good for nothing."

- Out of the political gridlock and ineptitude, Trenin says, emerged "a guy who is actually doing things, who is very practically minded and is not afraid to take responsibility onto himself."

The bottom line: "Within a couple of months of his appointment as prime minister, he became the figure on whom the last hopes of so many Russian people were pinned.”

Putin and the West: End of an embrace

Many in the West were prepared to embrace Putin as well.

Behind the scenes: Daniel Fried, a diplomat with decades of experience on Russia, was on hand for the 2001 meeting in Slovenia after which George W. Bush infamously remarked that he'd looked Putin in the eye and been "able to get a sense of his soul."

- “I remember when Putin approached us his whole body language was open and positive, very much unlike the aggressive strut he has now," Fried recounts. "I said to [Condoleezza] Rice, ‘this is going to be great,’ and it was good. They got along, strong personal chemistry.”

"We all assumed at the time that despite his KGB background, he was going to continue on the Westernizing course that Yeltsin had pursued," says Alexander Vershbow, U.S. ambassador to Russia from 2001 to 2005.

- "Yeltsin had assured [Bill] Clinton and others, 'don't worry, he'll continue our work.' It soon became clear he was a very different character."

- The U.S.-Russia relationship was strengthened by Putin's offer of support after 9/11, but it began to sour over the invasion of Iraq and, in particular, the color revolutions in Georgia (2003) and Ukraine (2004), for which Putin blamed the West.

Vershbow saw Putin's brutality in Chechnya, callous handling of the Beslan school massacre and crackdown on independent media as signs "he was clearly not just trying to restore stability, but to re-centralize power and remove checks and balances."

- In meetings at Camp David weeks before Khodorkovsky was arrested, Vershbow says, Putin was notably cold but "betrayed nothing" about his plans.

- "Then the boom was dropped and we realized there was less communication than we thought there was."

Putin in power: Confidence and concern

By the time Bill Burns arrived in Moscow as U.S. ambassador in 2005, he says, Putin was feeling both "cockier" and more suspicious of what he saw as U.S. meddling within his sphere of influence.

Behind the scenes: "Clearly we were already heading into an uneasy period in relations," Burns says, noting that the tone was set from the day he presented his credentials at the Kremlin.

- "You walk through these long corridors to the huge ornate halls, then you come to these two-story bronze doors. You’re kept waiting for a bit until they crack open, and out comes Vladimir Putin."

- "Despite the bare-chested persona, in the flesh he’s not so intimidating. But I remember him walking through the door and, in Russian, saying: ‘You Americans need to listen more. You can’t have everything your own way anymore. We can have effective relations, but not just on your terms.'"

The big picture: Putin had reason to feel confident. Oil prices had doubled in his first 5 years in office and were continuing to rise, and his early economic reforms were also bearing fruit.

- "He basically laid out a social contract for Russians which in effect was, 'you stay out of politics, that's my business. What I will ensure in return are rising standards of living,'" Burns says.

- Meanwhile, he "intimidated" elites and oligarchs like Khodorkovsky who didn't owe their positions to him.

The bottom line: "In a fairly brutal fashion, he re-established that sense of control in the power of the Russian state."

The economy: Soaring, then stagnant

Putin did not sustain his initial burst of pro-market economic reforms, and Russia did not sustain the growth rates that had burnished his image at home and abroad.

By the numbers: Russia's economy climbed from 12th-largest by GDP when Putin took power to 8th by 2009.

- It's now back to 11th, on par with South Korea despite having nearly three times the population.

- On a per-capita basis Russia sits 60th, between Costa Rica and Malaysia.

Why it matters: "A decade or so ago when he was riding high on high oil prices, that was the moment when he could have started to diversify the economy, to innovate a little bit, because there’s a lot of human capital in Russia," Burns says.

- "But he chose quite consciously not to do that because it would have come at the expense of what mattered most to him — political order and control."

The big picture: That left the Russian economy essentially frozen in time, heavily dependent on oil, gas and other natural resources and falling further behind the West. Highly educated Russians left in droves.

- Russia's stalled economic development will be, Trenin says, "his most important failure.”

The bottom line: "Putin could be seen as someone who put Russia back on the map as a great power actor," says Alina Polyakova, a Russia expert at the Brookings Institution. "But he could also be seen as the person who relegated Russia to global irrelevance."

Putin's promise: "There will be no vacuum of power"

"I assure you that there will be no vacuum of power, not for a minute," Putin told the Russian people on New Year's Eve 1999, as he assumed the acting presidency upon Yeltsin's sudden resignation.

- Few would have guessed he'd still be in power — still keeping that promise — two decades later.

- Analysts seeking to explain Putin's success in attaining and holding power often emphasize two things: his training in judo and his career in the KGB.

“What struck people and inspired people to hope was that Putin was never trained as a politician, so he doesn’t speak the language politicians speak all over the world," Trenin says.

- "But not having a politician's training does not mean he has no training," Trenin adds, noting Putin's aptitude for delivering different messages to different people and sounding "very convincing" to each in turn.

The other side: "Putin was an operations officer," says Michael Morell, who joined the CIA not long after Putin joined the KGB and rose to acting director.

- "Operations officers see opportunity everywhere, and they look for situations to take advantage of. I think he brought that mindset into office."

- In Putin's Russia as in the Soviet Union, Morell says, the security services are big, skilled, aggressive and empowered.

- As Åslund puts it: "Putin's style is more information than violence, but there's always the chance somebody gets killed."

The bottom line: Putin's initial democratic pretense cloaked a man still firmly rooted in the Soviet era. He has always regarded Western claims to openness and democracy as a hypocritical facade, Khodorkovsky says.

- “There are politicians and there are some very powerful people behind their backs,” he says of Putin’s worldview. “They control everything, and everything else is just windows in a shop.”

Go deeper:

Subscribe to Axios World to get more reporting like this in your inbox.