There have been 100 days of fighting in Sudan and the conflict has wrought a devastating human toll, reigniting ethnic violence and sparking fears it could destabilise the wider region.

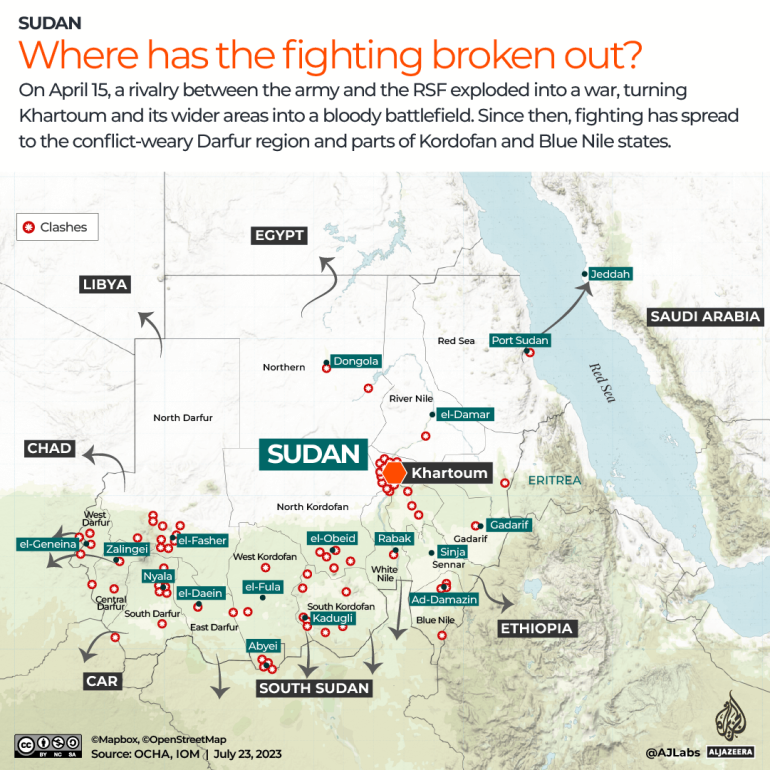

On April 15, a rivalry between the army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) exploded into war, turning Khartoum and wider areas of the capital into a bloody battlefield. Since then, fighting has also spread to the conflict-weary Darfur region as well as parts of Kordofan and Blue Nile states.

A flurry of diplomatic initiatives to halt the war has failed to yield any concrete results as the rival sides are locked in a battle for survival – one that both think they can win outright without having to engage in meaningful negotiations, analysts say.

What initiatives have been tried so far?

In May, the two warring sides agreed to send negotiating teams to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to start talks brokered by Riyadh and Washington. At least 16 ceasefire agreements followed – each of them has collapsed.

Negotiations were suspended a month later after the army withdrew its participation accusing the RSF of a lack of commitment.

Reports suggest that talks may resume as the army delegation returned to the Saudi city on July 15, but no official statement has been made so far.

As the Jeddah talks failed and fighting continued, the African Union (AU) unveiled its own plan.

It included the start of a political dialogue among the country’s military, civilian and social actors not just to resolve the ongoing conflict, but also to set up constitutional arrangements for a period of transition and the formation of a civilian government.

Unlike the Jeddah talks, the AU summit was attended by members of a civilian coalition that shared power with the military before General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as “Hemedti”, orchestrated a coup in 2021 ending the country’s fragile transition towards democracy.

But besides convening three times – the last meeting was on June 1 – and issuing broad statements, the summit has not delivered any meaningful results yet.

Then came the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) negotiating attempt.

The regional body, composed of eight countries around the Horn of Africa, set up a quartet committee – including Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti and South Sudan – to address the Sudanese crisis. But an IGAD meeting on July 10 was boycotted by the army’s delegation, which accused the quartet’s lead sponsor Kenya of lacking impartiality.

Instead, the Sudanese army welcomed a summit held in the Egyptian capital, Cairo, on July 13, chaired by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, with whom Sudan’s top general al-Burhan enjoys long-lasting ties. The meeting was attended by leaders of Sudan’s seven neighbouring countries along with the secretary-general of the Arab League and the African Union Commission (AUC) chairperson.

The Egyptian president outlined an initiative to establish a lasting ceasefire, set up humanitarian corridors for humanitarian assistance and build a dialogue framework that would include all Sudanese political parties.

Participants in the roundtable agreed to form a ministerial mechanism composed of the foreign ministers of the seven states to resolve the ongoing conflict. The plan was praised by the military and the RSF.

Too little cooperation, too much competition

Having different diplomatic initiatives is not beneficial to a solution, experts warn.

“There is an egregious failure of diplomacy here, we see too much competition and too little cooperation,” said Alan Boswell, International Crisis Group’s project coordinator for the Horn of Africa.

“Diplomacy has not been there and this is because it’s not high enough on the agenda, especially for the US,” Boswell said, noting that Washington has not done enough in its traditional coordinating role.

Rifts among regional players, who could exercise pressure on the two warring sides to agree to a ceasefire, pose another obstacle.

The UAE has not been directly involved in any roundtable and its simmering competition with Saudi Arabia could be an obstacle to its inclusion in any process.

Also, Cairo’s relations with Abu Dhabi and Addis Ababa have been strained for a while, while Washington has enjoyed better times with the UAE which refused to condemn Russia’s aggression of Ukraine.

“Existing tensions are proving perhaps too much to get everybody sitting at the table,” said Boswell.

Regardless of the number of negotiating platforms, none of the warring parties is genuinely interested in engaging in negotiation at this stage, said Kholood Khair, an expert on Sudan and founding director of Confluence Advisory.

“They both think that they can win and [as long as] both think they can win, they will continue to push militarily not just to have more bargaining power, but to win outright,” Khair said.

Both sides though have shown interest in the mediation efforts not to find a solution, but to rather buy time while gaining international legitimacy.

“We know that they have been rearming, so they are not entering any mediation at all seriously or in a way suggesting that they want to be serious,” Khair said.

Lack of legitimacy

Civilians have found themselves caught in the middle of the conflict.

Since the war started, at least 3,000 people have been killed, Sudan’s health authorities said. About 2.6 million people are now internally displaced, while more than 750,000 crossed into neighbouring countries, figures from the International Organization for Migration show.

Save the Children reported “alarming numbers” of teenage girls being raped, with cases involving girls as young as 12.

In Darfur, where the conflict has taken its own dimension pitting Arab communities against members of the non-Arab Masalit tribe, an increasing number of testimonies and documents describe attacks mounting to ethnic cleansing perpetrated by Arab fighters along with members of the RSF, which has denied such allegations.

The fighting in the Sudanese western region has reignited fear over a replicate of the atrocities that took place there in 2003 when more than 300,000 people were killed.

The UN office for human rights said last week it had credible information that the RSF was behind the killing of 87 people whose bodies were found in a mass grave near el-Geneina, the capital of West Darfur.

While the RSF has a military advantage in areas where there is active fighting – especially in Khartoum and Darfur – there is ample evidence showing its troops looting houses, pillaging residential areas and perpetrating sexual violence, making the group lose legitimacy.

On the other side, the army has shown to be unable to fight back the RSF while relying more and more on allies of the former Omar al-Bashir regime.

“Neither side has the legitimacy to rule Sudan, but you can’t whisk them away either,” said Boswell. “We have to see this as a two-step process: negotiations to end the conflict which must then move to a wider political process.”