The Little Haiti neighbourhood is barely five miles from glitzy Miami Beach, but it feels a world away. There’s no whiff of ocean here. Miami remains largely segregated and almost all the people sweating their way down Little Haiti’s streets are black. Many shop signs are in Haitian Creole, derived from French: “Mete Mask, Mesi” means “Put on a mask, thank you.” Just by Little Haiti Soccer Park, tired-looking locals board a bus. But beside them, a sign in big mock-silver letters announces the neighbourhood’s future: “MAGIC”.

A new high-end development, Magic City, is arising on top of what used to be a mobile-home park. Hipster shops are opening: Scarab handmade cycles and Booktanica, a wine bar that sells books. House prices are shooting up. In 2012, according to Zillow, the average home in Little Haiti cost $99,600, just 38 per cent of Miami Beach. Today the price is $414,000, fractionally more than Miami Beach. Many new buyers in Little Haiti are investors using limited-liability corporations. They are betting on a future when this neighbourhood will benefit from a previously disregarded asset: its elevation. An average of seven feet above sea level, Little Haiti should outlive Miami Beach. If so, today’s poorer residents will be priced out. Miami is Ground Zero for a new phenomenon that will reshape the world’s coastal cities: climate gentrification.

Before I go on, a note to those readers who will relish the irony of my flying to Miami to write about climate change: I came here for a mix of work and family reasons, and am carbon-offsetting my flights, without claiming that’s a solution. Like the climate scientist Michael Mann, I don’t believe that individuals voluntarily cutting their emissions can fix climate change. The problem is too big for that. Only international collective action, especially carbon pricing, might work. I know this sounds like a convenient self-justification. It could be that, and true nonetheless.

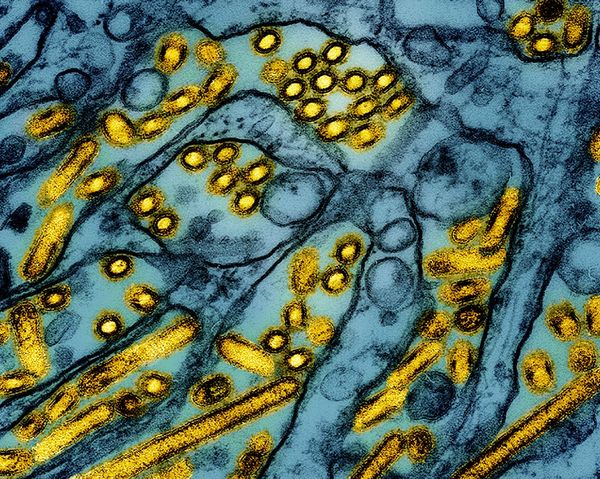

In any case, Miami is the perfect place to gauge how climate change will redraw maps. This will become the world’s “most vulnerable major coastal city”, predicts economic think-tank Resources for the Future. Miami may be gone by 2100, undone by hurricanes and the rising ocean. Almost impossible to defend because it’s built on porous limestone, it also floods from below. Streets on Miami Beach already overflow regularly, even on dry days.

For now, South Florida is booming regardless. I hadn’t been here since 2016, and the plethora of new buildings was almost claustrophobic. Much of the US tech and finance scene jetted in during the pandemic. Some of this is denial of reality. Some of it is 0.01 percenters such as Ivanka Trump or Tom Brady who hardly care what price — if any — they might get for their homes in 2040. But the biggest boom is inland.

The phrase “climate gentrification” was popularised by a Harvard study of Miami house prices in 2018. The researchers found that price rises in higher-lying areas such as Little Haiti had outpaced those in lower ones like Miami Beach since about 2000. This is climate change hastening the gentrification of poor neighbourhoods. Miami real estate agents used to ignore rising sea levels, then pretended the problem had been fixed by what look like waist-high garden walls. But lately Miami market thinking is shifting from “Location, location, location” to “Elevation, elevation, elevation”. I also liked “Sell low, buy high”.

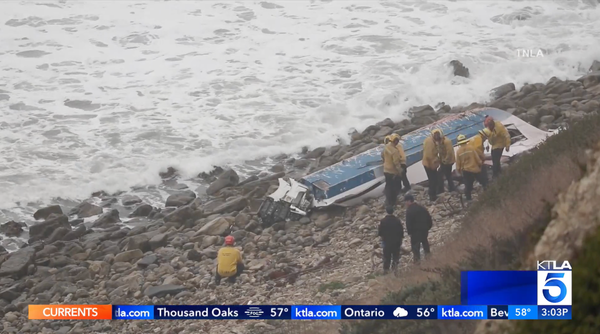

The collapse of the beachside Champlain Towers South building, which killed 98 people in June, only raised anxieties about the ocean. The collapse remains unexplained, but one theory is that water penetrated and corroded the building’s structures. Insurers are getting antsy, too. Buying flood insurance on homes in South Florida’s at-risk areas is becoming punitively expensive, while the federal government is not keen to bail out homeowners after the next hurricane. Hence the appeal of Little Haiti.

What starts in Miami will go global. About 40 per cent of humanity lives within 100km of a coast, and many coastal cities share Miami’s social structure: rich neighbourhoods on the beach, poor ones inland. Think of Rio de Janeiro, Los Angeles or Cape Town. As seas rise, the most expensive places are at the highest risk. In Istanbul, for instance, the choicest coastal bits of the Kadiköy neighbourhood could go under.

When coasts go from amenity to threat, coastal cities lose their attraction. Already, most of these places have shed their original function as ports. In coming decades, they could depopulate, creating a new, blue global rustbelt. We might be returning to the location hierarchy of the Middle Ages, when the hill was the most strategic point in town, the place to build your fortress. The Little Haitis of this world could be due an upgrade. The neighbourhood only officially acquired its name in 2016. The Magic City moniker may soon supersede that, until eventually this neighbourhood is abandoned, too.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2021