What in tarnation is “tarnation?” Why do people in old books exclaim “zounds!” in moments of surprise? And what could a professor of linguistics possibly have against “duck-loving crickets?”

I’ll get to the crickets later. But what unites all these expressions is a desire to find acceptable versions of profane or blasphemous words. “God” becomes “gosh,” “hell” becomes “heck,” and “damnation” becomes “tarnation.” In a similar vain, the rather antiquated phrase “God’s wounds” turns into “zounds.”

This lexical skirting of religious sensitivities falls in the category of expressions known as “minced oaths.” They are a kind of euphemism: an indirect expression substituted to soften the harsher blow of the profane.

Bloody heck!

As a lifelong student of language, I celebrate the variation of minced oaths and delight in comparing them with other euphemisms and slang. They provide examples of how people craft language to simultaneously conform and rebel, while building social cohesion.

Both slang and minced oaths are forms of synonyms – words used to replace others while conveying the same core meaning. But minced oaths have historically performed a very specific role: providing a weakened but socially acceptable form of an actual religious oath, swear or curse.

The earliest use of the term “minced oaths,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, was in 1654, when elders in the Banffshire area of Scotland were criticized for using them.

But the use of them had been around for at least a century before then. The playwright Christopher Marlowe used “zounds” as early as 1593 as an exclamation: “Zounds hee'l raise vp a kennell of Diuels.”

The term “bloody” was first recorded as the British now use it in 1540 and originally had no religious connotation. It was only centuries later that it was ascribed one, potentially standing in for “by her lady” and “God’s blood” and thus becoming somewhat of an adopted minced oath.

The compound “gadzooks” – perhaps from “God’s hooks” – makes a written appearance in the second half of the 1600s in a play by Irish writer Thomas Duffett: “Now to get off, gadzooks, what shall we do?”

Surprisingly “gosh” and “heck” are late comers – “Gosh” does not show up until 1757 and “heck” as an interjection only takes off at the end of the 19th century.

Up until the late 1800s, the most common expletives in English had some kind of Biblical reference, but as Melissa Mohr explored in her history of swearing, “Holy Sh*t,” these blasphemous oaths started declining in the 1700s and gave way by 1900 to profanity based on physical attributes and functions – body parts, sex and excrement. Mohr links this change to the decline of the Christian church as a central powerbroker in people’s lives. As Mohr writes, “Obscenities took the place of vain oaths to become our swearwords.”

With this transition the impact of minced oaths waned from the tantalizingly close to the profane to mere humorous airs with a knowing wink. It is one thing to earnestly swear, “Begorrah [By God], I will not fail!” and another to have Gomer Pyle from The Andy Griffith Show humorously exclaim “Golly!” when something surprises him.

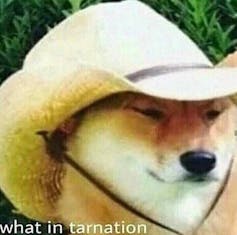

While some minced oaths have persisted – one even becoming part a popular hat-wearing dog meme – many have fallen from common usage. Others have slipped from being seen as profane to become simply mild expressions, like “Sam Hill ” for “hell.”

Either way minced oaths live on, getting recycled or created anew today to provide humor, or a range of emotional force. Using “fudge!” after a paper-cut allows for restrained fist-shaking at the universe. And if family and friends can settle on the same minced oaths, they can better commiserate with their own in-group slang.

Far from feck–less

Meanwhile, minced oaths based on modern sexual swearing can be all kinds of fun. On the popular NBC series “The Good Place,” a popular running gag – with a possible wink to the censors – is that characters are unable to utter obscenities. When they attempt to, they end up saying “fork,” “shirt” or “bench” instead of, well, you can use your imagination.

With enough exuberance thrown behind these terms, residents of The Good Place can draw humor from the contrast with the profanity viewers anticipate.

Similarly the Irish TV show “Father Ted” – which follows a trio of Catholic priests exiled on a fictional island off Ireland – employed “feck” as a regular part of the dialogue. The pure exuberance and frequency of its use by characters creates the comedy.

The popularity of these shows fostered an uptick in the use of these minced oaths, as people put their comedic effect to work in their own lives.

But sometimes, defanging profanity just doesn’t quite hit the mark. In her research on swearing, Emma Byrne, author of “Swearing is Good for You,” finds that “the frisson of taboo” is required for the therapeutic qualities of swearing like pain relief. As Byrne reports, learning swear words early on in one’s native language has a measurable physiological effects. Cursing helps relieve pain, raise the pulse, and sharpen the memory.

Yet minced oaths provide some degree of power and latitude at times of social control. For instance, before the Quiet Revolution, the Quebecois French created a set of words, called “sacres,” to defy the Catholic Church. People began to use words associated with church rituals as exclamations and interjections.

With some slight modifications, words like “tabernacle” – the place in a church where items of the Eucharist are held – are used in place of a profanity in Quebecois French. For example, after your favorite team loses again, you could shout “Tabarnak! Encore une défaite!” Or, for a gentler profanity, “Tabarnouche!” of “Barnak!” can be used.

… about those ducks

Because minced oaths allow for a small scream into the void while avoiding taboo words, parents are often avid fans. Some families pass them along like heirlooms. My family inherited “Holy Cow” and “Heavens to Betsy,” from grandparents.

When I became a parent I shifted my own swearing, and somehow I landed on variations of “duck-loving crickets.” Perhaps phonetic similarities to actual profanities or the intonational cadence qualified them as somehow forceful yet also purposefully missing the mark.

My daughter rejected mine, but adopted “shiitake mushrooms” as her exclamation, drawing out the first syllable.

You see, there is always room for more in the mixed bag of minced oaths.

Kirk Hazen receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)