An old cliché maintains that imitation is the highest form of flattery, but that principle barely applies to Mel Brooks. When Brooks spoofs something, he doesn’t just imitate. He recreates, and sometimes he swaps our feelings about the original art with his spoof.

Picking the best Mel Brooks film is difficult, but the one that imitated to the point of perfection is doubtlessly 1987’s Spaceballs. Here’s why the movie still holds up well, and why it’s more subtle than you might remember. (Yes, subtle!)

Perhaps the greatest thing about Spaceballs is that it actually looks great. Although the production is designed to emulate the original Star Wars trilogy, the special effects and sets are occasionally convincing enough to make you forget you’re watching a comedy.

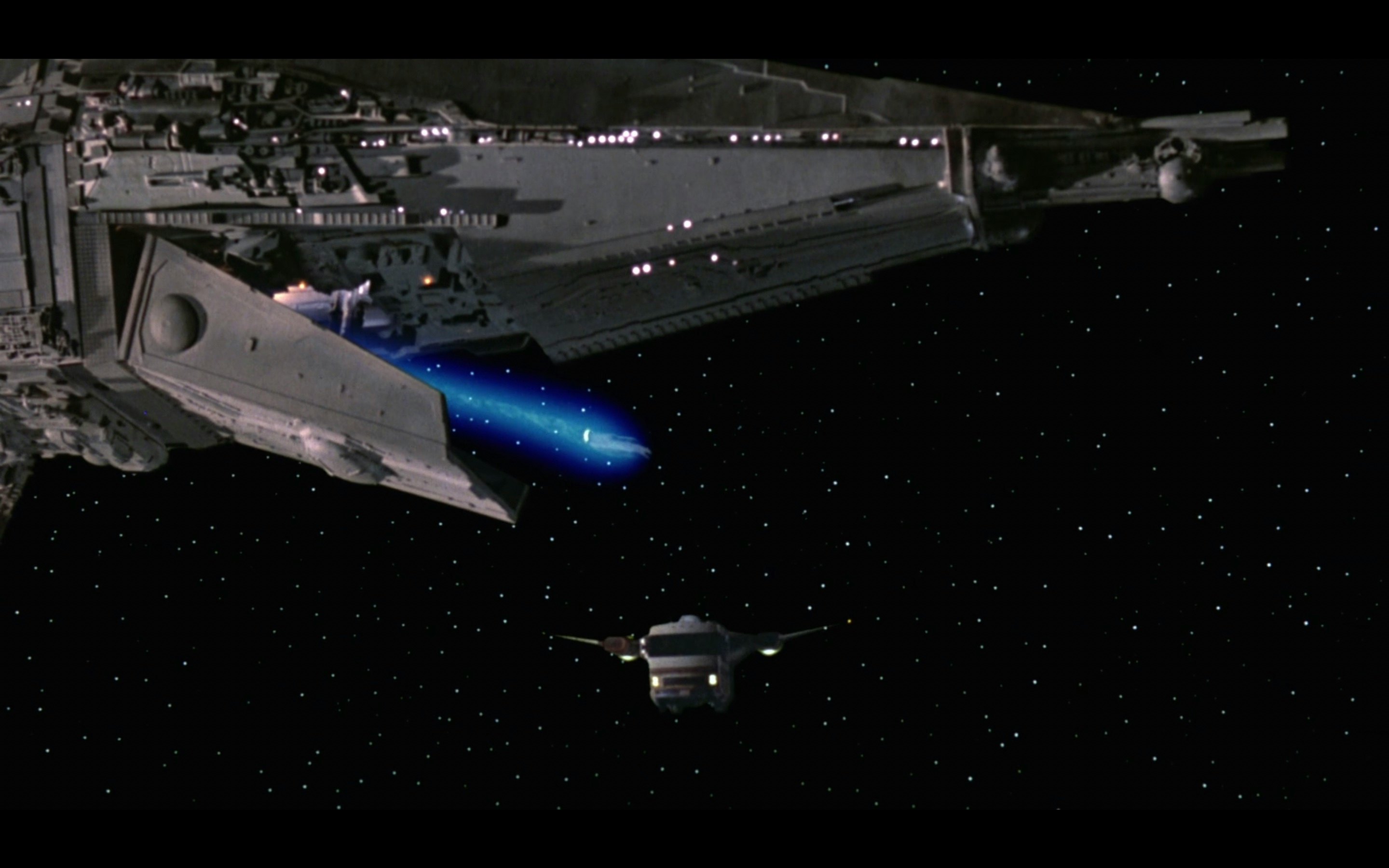

The very first scene contains a shot of the giant space cruiser Spaceball 1 advancing across the screen very, very slowly. This never-ending starship is a visual joke about the hugeness of Star Destroyers, but the Spaceball 1 actually looks legit. It’s long, but not goofy.

So while it's tempting to say that Spaceballs is funny because of the visuals, that’s really only true when the visuals are trying to make you laugh. What everyone tends to forget about Spaceballs is that it's built to look like a real space opera, not a knock-off. The production designer was Terence Marsh, who also worked on The Hunt For Red October, Clear and Present Danger, and The Shawshank Redemption. And if you’re wondering why the ships look so good, that’s because the VFX and models for Spaceballs were done by Grant McCune, who worked on... Star Wars.

Everything about the way Spaceballs looks is the foundation for why the comedy works. Even when President Skroob (Brooks) is “beamed up” by Snotty (Jeff MacGregor), the beaming effect looks pretty good! Princess Vespa’s (Daphne Zuniga) space car is cool, and when it rockets away at the start of the film you’re dealing with something that looks at least as good as a Roger Moore-era Bond film.

So, the “reality” of Spaceballs, while hyperbolic and ridiculous, is visually rich. Even the decision to make Lone Starr’s (Bill Pullman) spaceship a motor home is inspired. Sure, the Millennium Falcon was cool, but what Spaceballs does is make the idea of the Millennium Falcon more realistic by making it a joke. If two lowlifes lived on a spaceship, then wouldn’t it make sense that said spaceship would be trashy? This clever detail touches at a slightly deeper truth lurking underneath the Star Wars motifs. Again, it’s not that Brooks and his collaborators are imitating Star Wars; Spaceballs is an interpretation, and an insightful one at that.

The plot of Spaceballs is also smart and, with a few tweaks and some different dialogue, could exist in a “serious” work of science fiction. One planet is running out of air, so the villains want to steal air from another planet. The science here is wonky, but is it any less wonky than, say, Guardians of the Galaxy?

There’s also an interesting degree of ironic foreshadowing with the Spaceballs concept of the “air shield” which protects Planet Druidia. In Rogue One, a Star Wars film released nearly 30 years after Spaceballs, we got a “Shield Gate” over the planet Scarif. In plot terms, it was functionally similar to Spaceballs. This isn’t to say Rogue One was riffing on Spaceballs, but rather that Spaceballs was creating iconic sci-fi imagery, even if by accident.

There are so many good gags in Spaceballs that listing them would actually ruin the movie. If you’ve never seen it before, it’s an excellent comedy that hits even better now than it did in 1987. The jokes work because the sci-fi foundation is strong, while the charm of its production details would be almost impossible to recapture today. These days, a spoof like this wouldn’t be called a comedy. It would just be called “fanservice.”

Spaceballs is currently streaming on PlutoTV and Amazon Prime.