There are many universal languages, and almost none of them are actual languages. Movies often get the moniker, as does soccer. Video games are another type of universal language, although games often have their own regional biases and focuses. A player who grew up with Indiana Jones movies might have a different understanding of Nathan Drake, for example, than one who didn’t. But the distance is shrinking daily, with games like Fortnite focusing less on the cultural details and more on the shared experience.

Arguably, this started with Tetris, a game that predates even Super Mario Bros. The game was born in unlikely circumstances. Tetris was created by Alexey Pajitnov, a researcher at the Soviet Academy of Sciences in what was then called Leningrad and is now known as Saint Petersburg, during his spare time, on a computer with no graphical interface, with zero understanding of the greater video game industry.

It was a long, complex road from the Soviet Union to global domination, halted in no small part by bias against any sort of content emanating from the USSR. But once the game debuted in America, proudly brandishing its Soviet heritage, it stuck. Countless iterations of its core gameplay, fitting falling four-block tetrominoes into lines, have emerged.

Tetris 99, which came out in 2019 and is currently free for Nintendo Online subscribers, is a particularly clever iteration. It takes the universal language of the battle royale that Fortnite popularized and brings it to another universal language, Tetris.

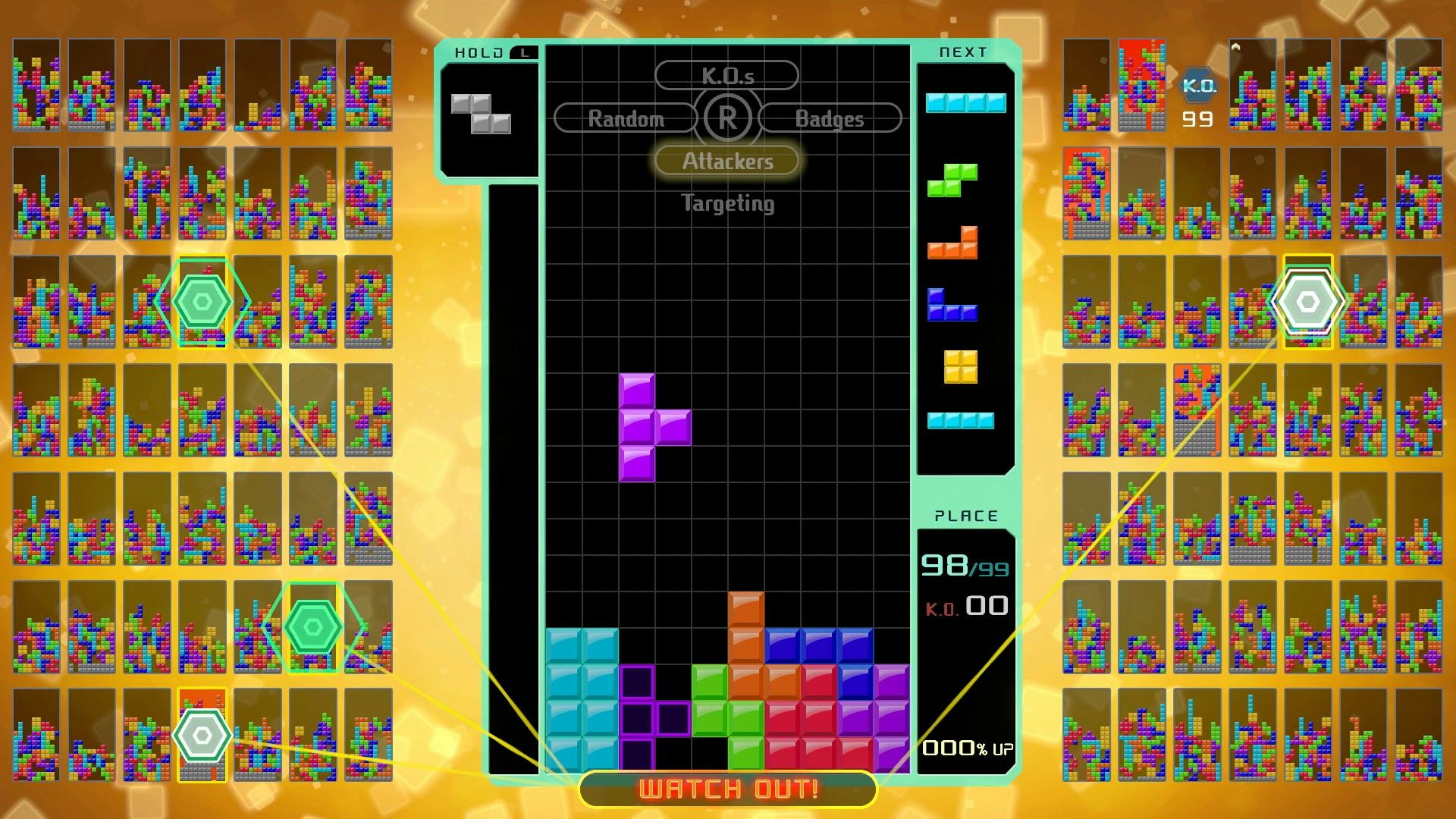

Tetris 99 has two levels of gameplay: first is the classic building and elimination of Tetris, and then there’s dealing with everyone else. Tetris 99 makes the concept of “garbage” lines crucial to gameplay. Garbage lines are ones that the game artificially adds below your screen, making the room to solve the puzzles of Tetris smaller and smaller.

Garbage lines are the weapons of choice in Tetris 99. Frustratingly, the game offers no tutorial or explanation of how it works, which is why a guide (like Kotaku’s) is very helpful. Clearing one line does nothing, but clearing two sends one line of garbage, clearing three sends two, and getting a tetris of four clears sends four. You can choose from four targets, including whoever is targeting you, any one of the ninety-eight other players who is nearing the end of the line (called a K.O), anyone who has earned what are called badges, or a random selection.

Players have a chance to fend off a garbage attack by clearing their own lines, and are incentivized to go for the K.O on others not just by competitive drive, but also by getting a chance to earn the aforementioned badges. Each K.O is a “bit” of a badge, and they steadily become exponentially harder to earn.

Badges can make you a target: they multiply the number of garbage lines you send out. As per Kotaku’s explainer, it comes out to twenty-five percent more for the first badge, fifty percent more for the second, seventy-five percent more for the third, and 100 percent more for the fourth.

All of this takes place very quickly amidst flashing lights and upbeat techno music that resembles the original sounds of the game. It might take a few rounds to understand the game’s mechanics, but the learning curve is a small one if you’ve got, say, twenty minutes to spare. The games move quickly, even if you’ve made it beyond the initial stages, where the game speeds up.

Tetris is a universal language, a game that doesn’t need words to be understood. Tetris 99 slightly complicates things. It might not be the best, most comprehensive version of the game available—that’d be Tetris Effect—but it does what it wants to do perfectly. If you’re looking for a game that emphasizes competitive Tetris, this one’s a blast.