The early ‘90s saw video game consoles coming fully into the mainstream. The industry had gone on a wild ride in the previous decade, rebuilding itself after an industry-wide crash in 1983. Out of the wreckage and chaos came stability, mainly through Nintendo. Arcade gaming, where quality varied wildly, was on the wane. Instead, the focus shifted to home consoles, where longer experiences could be built to last players hours.

Nintendo so radically changed the nature of gaming that it helped to create an ecosystem of challenges. Rival Sega had spent the decade shifting away from its arcade focus, an effort that culminated with the release of the Genesis. It was a sign of Nintendo’s dominance that the new company specifically began marketing itself in opposition: cooler, edgier, with a trash-talking teenage hedgehog at the center of their campaign.

How would Nintendo respond to claims that it was mainly for kids? With the cutest, cuddliest dinosaur anyone had ever seen. It turned out to be the right move, with 1990’s Super Mario World getting a fresh coat of paint for the Game Boy Advance over a decade after its initial release in 2002 as Super Mario Advance 2. It’s available right now if you’ve subscribed to Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack.

Super Mario World was the first Mario game for the Super Nintendo, and that expansion gave developers a chance to grow. The team making Super Mario World was shockingly small compared to games being made today, with producer Shigeru Miyamoto estimating around 10 people total. But there were signs of growing expansion.

In a 1990 interview, director Takashi Tezuka recalled that up until Super Mario World, he had drawn all the characters in the series himself. But now, he “was able to give that work to others. In that regard it was a lot easier.”

There was the challenge of a new system, which had its own bugs and unique problems, as well as that of keeping the side-scrolling series unique after three games. Tezuka recalled “working late into the night” on new enemies and game mechanics, only for Miyamoto to “pop in and say ‘nope, that’s not gonna work.’”

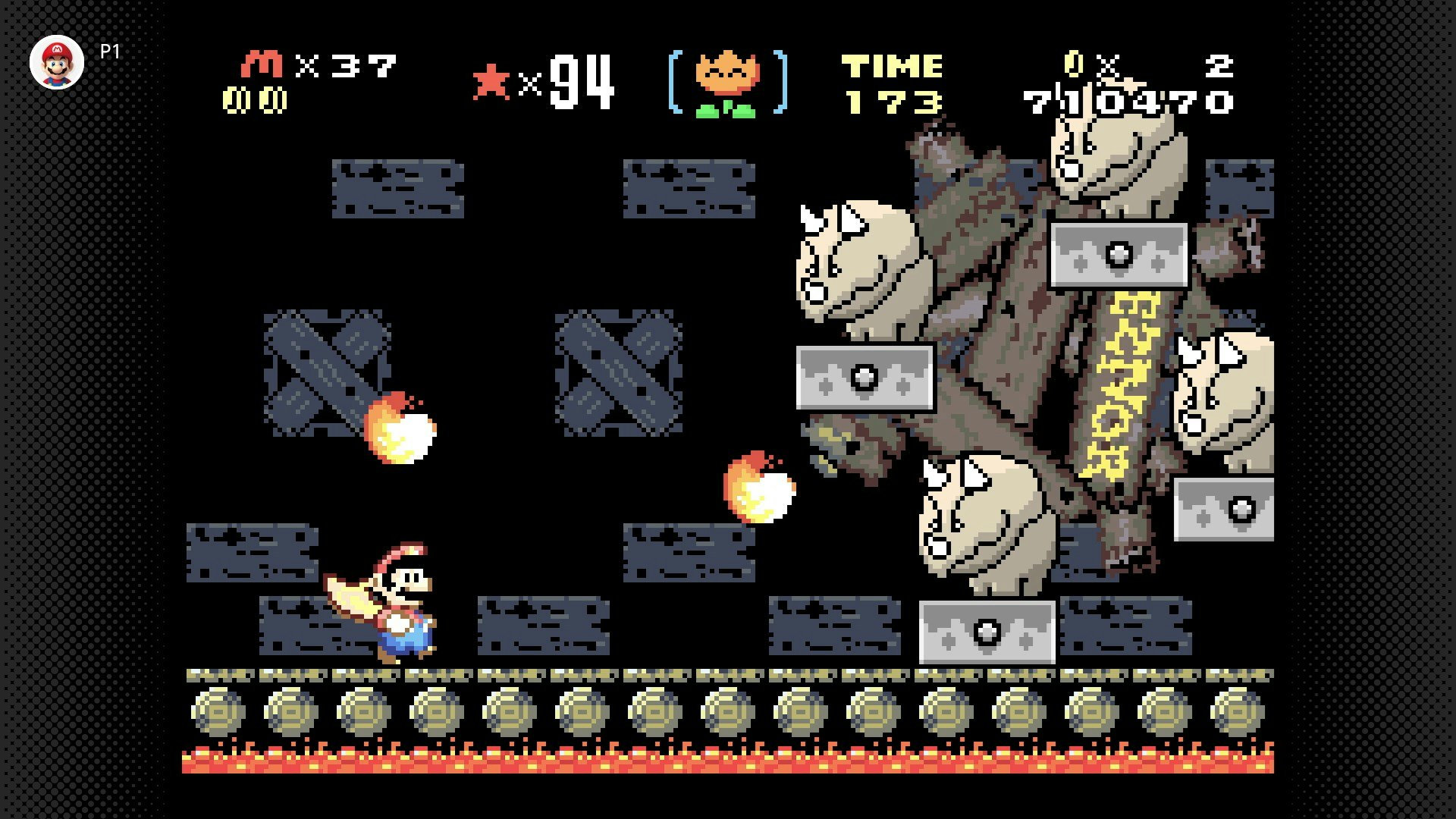

But the challenges came with their own rewards. With the SNES, Miyamoto “no longer had the restrictions on scrolling and the number of colors that the [NES] had, so it became much easier to depict things.”

Losing these restrictions meant that games had to change. The team had begun its work with the SNES by porting the last NES Mario game, Super Mario Bros. 3. Even with brighter colors and more detailed characters, something felt off.

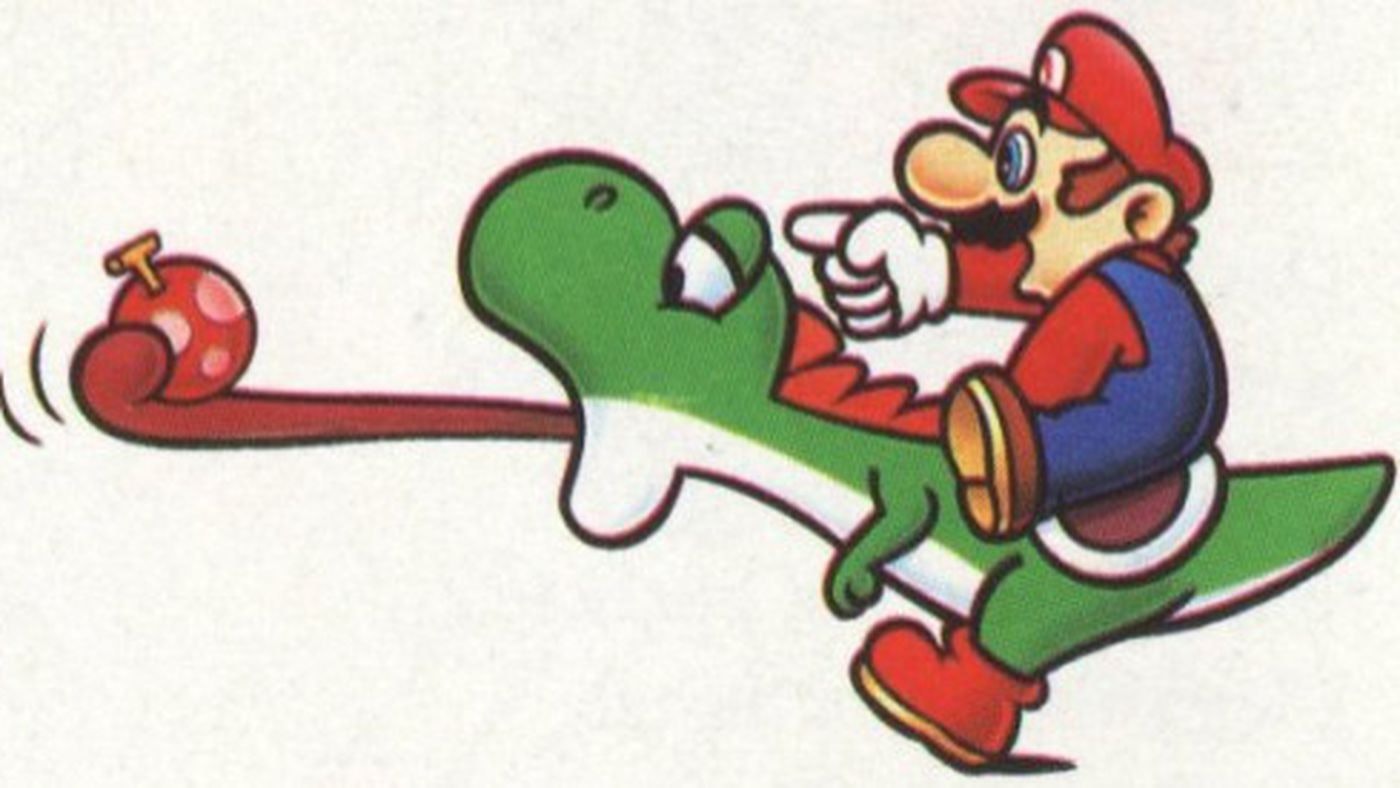

For all this talk of change, Super Mario World still looked a lot like the NES games. There was a continuity in aesthetics, undoubtedly, but playing a game with Yoshi offers a richer experience than one without Yoshi. Yoshi has his fruit, he can eat enemies, and shoot some of them out as fireballs. He also isn’t entirely under his rider’s command and will run away if the player gets knocked by a Chargin’ Chuck. He also provides another hit point, allowing a player to stay mushroom-enhanced even after a hit.

The world of Mario was expanding, pushing the limits of what worked in a 2D-scrolling world. The game’s levers and switches give it a homemade feel, like something Miyamoto and Tezuka worked up in their garage. And while it may not have given Nintendo the edginess needed to match Sonic, Super Mario World showed that the company has done best while betting on itself.