A telescope instrument originally designed to measure the effects of dark energy recently helped astronomers make an incredibly detailed image of our galaxy.

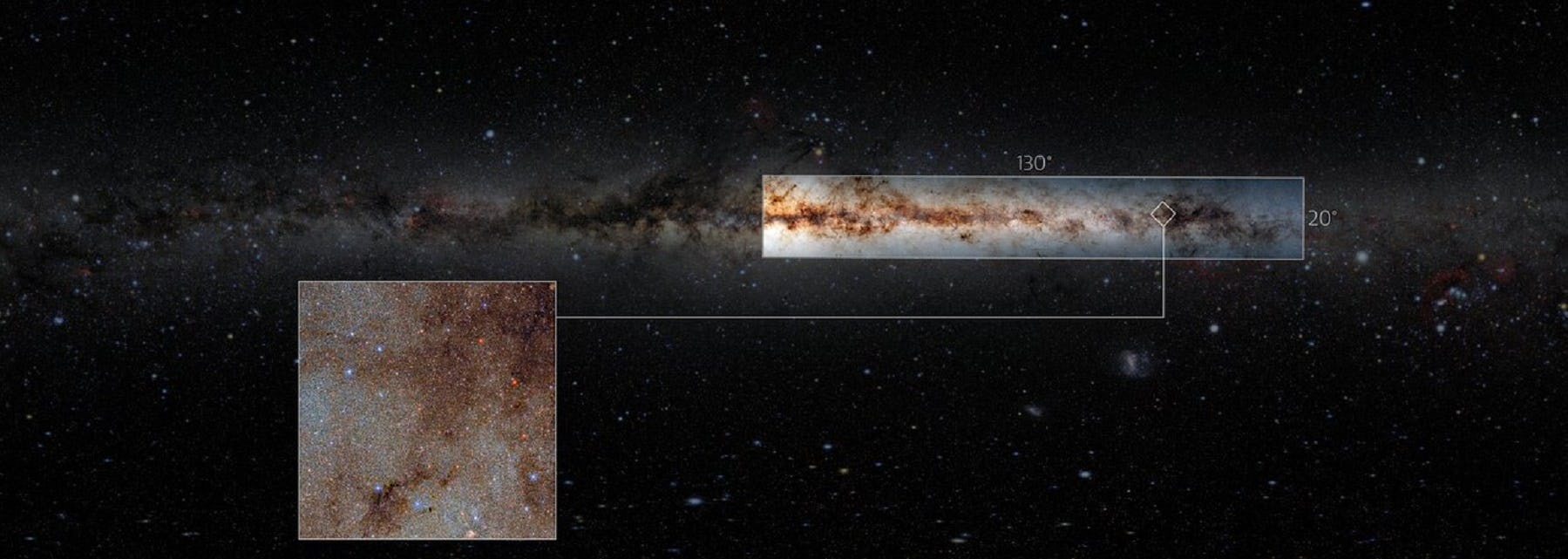

The image you’re seeing spans just 6.5 percent of the night sky, but it contains 3.32 billion stars — and each one is visible as a separate point of light, not part of a big, bright blur. Harvard University astronomer Andrew Saydjari and his colleagues compiled the image from 12,400 photos, taken in visible and infrared light using a telescope perched atop Cerro Tololo in Chile.

“Imagine a group of over three billion people, and every single individual is recognizable,” says Debra Fischer, division director of Astronomical Science at the U.S. National Science Foundation, in a statement.

You can explore the image in more detail online, and you definitely need to. The viewer takes some time to load, but it’s worth it if you’re into, you know, breathtaking views of the cosmos. Scroll around, zoom in on interesting features, search for specific stars (it’s like Google Maps for the Milky Way), and try to count them all.

This detailed catalog of the stars in our galaxy was a challenge to produce. The telescope’s near-infrared camera helped astronomers see through the clouds of dust that weave their way between the stars, blocking shorter wavelengths of light like visible and ultraviolet. But sometimes the problem is too much light. Our galaxy’s disk is packed so full of stars that they often overlap when you try to photograph them all, and the diffuse light from nebulae and star clusters makes it even harder to single out individual stars. Saydjari and his colleagues used a data processing program that helped predict the background behind each star, making it easier to separate one star from another.

“One of the main reasons for the success of DECaPS2 (the Dark Energy Camera Plane Survey’s second data release) is that we simply pointed at a region with an extraordinarily high density of stars and were careful about identifying sources that appear nearly on top of each other,” says Saydjari.

This is the largest catalog of stars ever assembled with just one camera. The Dark Energy Camera, a specialized instrument mounted on the telescope, was originally built for the Dark Energy Survey, a project that measured the expansion of the universe by looking at certain types of supernovae, galaxy clusters, and other objects in space between 2013 and 2019. Since then, it’s been involved in several other projects.

But as incredible as this image is — and it really, really is — it contains just a tiny fraction of the hundreds of billions of stars in our galaxy.