Talia Marshall on this life and the next

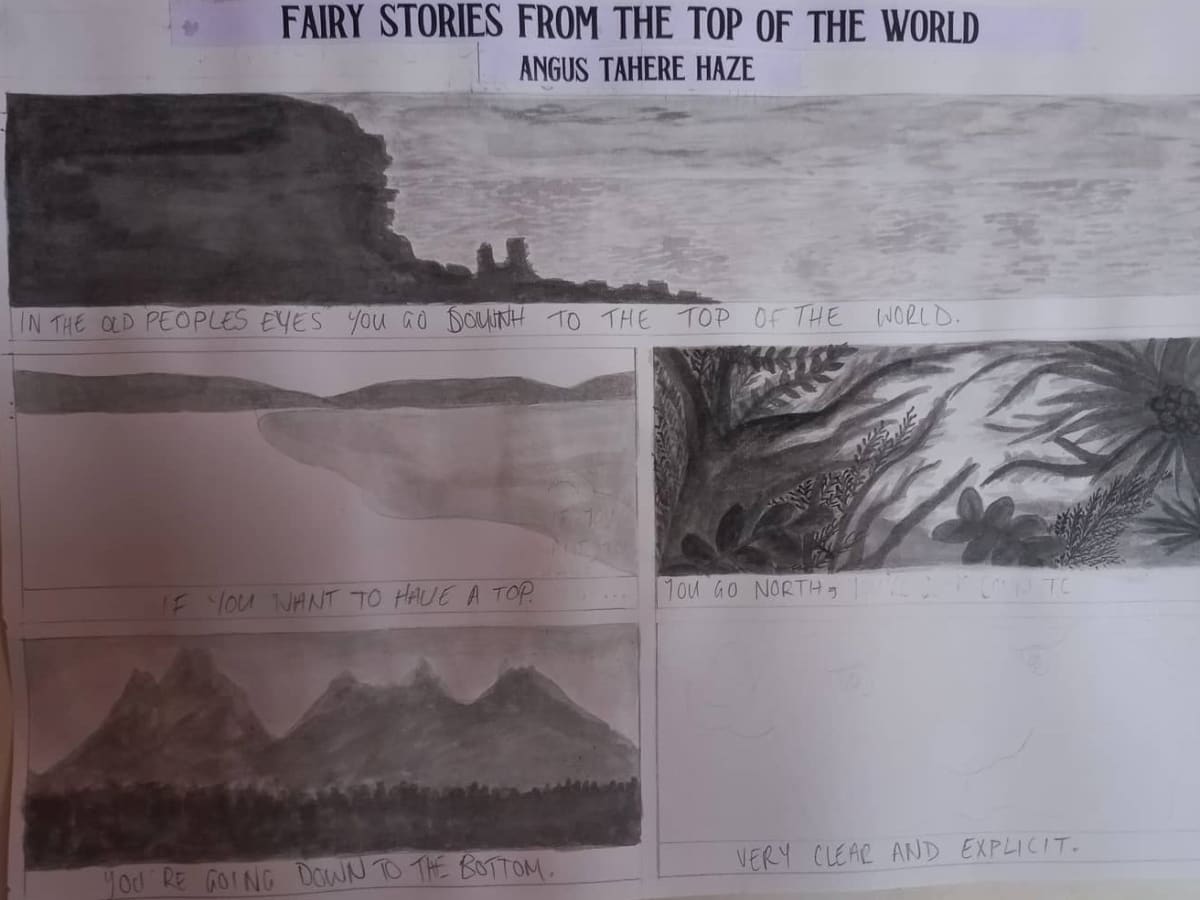

The week Keri Hulme died, Angus was already drawing her. After reading Keri’s short story they started making a comic based on Keri’s kupu. Angus was shy when they showed me. This is great! I said, because it was. But Angus shuffled the papers away to take home with them and I forgot about it.

When I was commissioned to curate this week at ReadingRoom I hit on the Spiral Collective, and the renewed interest in the feminist happening that published the bone people when no one else would. And then I remembered Angus’ comic about Keri’s short story. But Angus said it was too long. So I asked them to give me Keri at Ōkārito and the giant monstera in her immodest shack.

I wanted Angus to draw kōtuku and Keri with sturdy arms deciding whether to break out the good stuff or the Laphroaig. Keri flipping whitebait patties and popping champagne for the inevitable visitors. Keri waiting for that writer’s jackpot, after her Kāti Māmoe manaaki was over and the visitors had vanished: her solitude widening into the night and the roar of the sea and her imagination let loose and crackling through the circuits of her steelo-pad brain.

Angus was not as fussy about being alone, they liked plenty of company. And comics were the right medium for Angus because they could write and draw and possessed an arid sense of the absurd. They had just signed a comic book deal with an American publisher.

Angus was also organising a writer’s workshop up at the local ngā hau e whā marae for Becky Manawatu and me to deliver. We kept sending each other guilty, nervous messages or chatting on the phone about how Angus was doing everything while we pretended to each other that writers can’t organise anything except taking a book out of a paper bag.

I was worried we didn’t have enough funding to feed people, a Māori’s worst fear! I was worried that no one would come because we had left advertising it too late. I was worried people would want to come. I get avoidant when I’m anxious. But it was on my mind constantly.

We really wanted non-writers to come, as much as our kin, and thought they would get a buzz out of being in a bespoke book with some established authors. I was going to run a diorama workshop and Becky had a writer’s exercise plan. It was in serious danger of happening.

And then we had to cancel the workshop because the person doing everything was gone. I had let mahi get in the way of a friendship when I only truly believe in the latter.

I couldn’t face the hākari after Angus was cremated. And months later I’m still too tapu to be touched. I flinch if anyone comes near me. Although, I am touched, for sure, by losing one of my closest friends. It’s important to whakanoa by having a kaputī and eating something, anything, after someone dies. A chunk of carrot cake to make the world ordinary again. A smoky piece of pork with salt in the fat from the hāngī to lure you back from following them into the underworld.

But I’ve left it too late to whakanoa, and nothing I put in my body has any connection to my body. I am not really here. Sometimes, briefly, I can feel their face between my skull and my skin, and I touch my cheeks to feel for Angus, who left us just in time to catch the Matariki train when no one knew they had booked a ticket.

I am being evasive about describing a horror, because it is tika not to glamourise this kind of death. Angus was the sort of person who fantasised over their funeral. But who isn’t guilty of this? I know I want “Maneater” by Hall & Oates played as I’m carried out, because I’m hopeless with men, and have humiliated myself in multiple ways and I think that’s funny. Irony can still beat death in terms of last laughs.

At Angus’ tangi, I was in the welcoming line singing the old waiata I remembered from school, waiata I’d learned at this marae, Arai Te Uru, in the old whare, 30 years ago, before it burnt down. Now I was part of a group effort to make it cheerful, to try and make stepping back into Te Ao Marama feel okay for Angus’ whānau, even for a few festive hours. And then I spotted my son waiting near the front of the wharenui and I knew by the Nāti stiffness radiating from him that he couldn’t face the feast either. So, I fled the line, as the quiet scary whaea beside me, who had told me to stay put, went to help dish the kai. I found J by the sight of her massive curly Māori mane. She’d known Gus as long as me, we’d all met on the same social services degree almost a decade earlier, and I said to her,

I can’t do this, let’s go back to yours and have a drink.

Yea, that’s what I’m thinking, she said.

Twenty minutes later J came out of Countdown with multiple bottles of wine and refused to take any cash off me. Then we followed her very yellow V8 back through the suburbs to hers.

When Jacob, Angus’ patupaiarehe bff, first told me our e hoa was dead, in between howling and screaming, and crying more than I cried for my father when my sister told me he was gone, I asked Jacob,

But who is with Angus now?

And once I knew they were up at Arai Te Uru , the place Angus did the mahi, I let that one anxiety go. At least our e hoa’s body was being kept company. I half-apologised for not going to the poroporoaki to Angus in my head, saying: straight up Gus, if I have to hear one more story about how loved you are, and what a fucken tragedy your leaving us is, I’m going to start screaming and I might not stop. One of the many things about being human that Angus understood was the need to scream. The cheeky bitch probably wanted me to turn up and scream. The hākari and the poroporoaki are essential for processing grief, Māori do death well, but it was safer to be angry at J’s.

When Angus posted on socials announcing their true name and they/them pronouns two years ago, I rang them and said, Hey Gus. Later, Angus told me their name was partly about their rage. Becoming Angus was about owning their anger.

But at the tangi I realise it was also about their koro, who gave Angus their whakapapa and was nicknamed Gus. I eventually changed their name on my phone, which took them from the bottom of my contact list to the top. We had a pact about our pain. So, it was handy to have their name one bump away on my phone. I am much older than Angus, not quite old enough to be their mother, and I leaned on them. Angus helped me through multiple crises and knew what I mess I am. It’s a shame their immense capacity for love and care was viewed by too many in our tiny town as frightening.

Kia kaha is a phrase that usually annoys me, but when Angus’ mum Karen raised a shaky fist in the air and told us all to be strong at the conclusion of their delicate tribute I was humbled. I felt equally humbled by Ray, their father, who sang the Liverpool FC anthem in a soft Scouser accent, telling his water-loving baby that they would never walk alone.

Afterwards, I still sat there at J’s making a hit list of cunts I was going to take out for stealing the darling that looked after me and let me be outrageous. Angus was a Gemini, like my Nana. And I’m still trying to make sense of what an original person they were. Angus was unique in a sea of people that claimed to be, although they had finally found a cool crew. There was a doubleness to everything they said and did.

J chuckled about the time Angus put up their hand up in class so that they could tell the lecturer that J had had her hand up the longest and she loved Gus forever after that. The first time I properly saw Angus was during an introductory ballgame intended to humiliate us all as new social servant students forced onto a camp. Angus dressed like Nana and Harry Styles then, before Harry Styles started dressing like my Nana. I noted that this was how the cool kids were dressing these days, and how courteous Angus was with the ball. We had gone to the same high school and now the early nineties were back. I was wearing my trusted unitard that day because I couldn’t find my bra.

Angus made friends with me later in the year by shyly asking if I wanted to make a zine with them. What’s a zine? I asked, hamming up our age difference. And then I agreed because I was flattered. We never made a zine, but we made friends. Gus confessed to me they had an anger problem which was scarcely believable to me. I told Angus they were just slumming it with too many middle class white people. Their innate sense of right and wrong was much purer than the social justice we were being taught about. They also sought out and encouraged people everyone else found unbearable. Like me.

During Gus’ vegan phase they made a berry cheesecake out of nuts that took 200 hours to ferment into cream cheese and 100 kilos of cashews. I teased them about knowing too many people with rich parents again, and now I feel bad I didn’t try any dessert, after Gus had gone to all that trouble, I was too wasted by then.

My son sat mute at J’s table. He adored Angus too, they were closer in age and cool bandwidth than me. They both possess weird but perfect taste. Especially in music. Angus asked him to be in their band, beautifully named Fuckpalace. Angus always had some project they were cooking up, looking for ways to bring creative misfits together.

One of the last nights I got on it properly with Angus, my son was there too, he was watching Van McCoy’s “The Hustle” on YouTube. Jimmy Saville’s dancers were wearing bunny swing dresses and drifted in white over the dark screen. Angus said they could do those moves and stood up in their black sparkly shorts and did them well. And then Angus asked if they could play a song. Angus had a sweet but extremely determined voice when it came to putting on songs. I can’t remember if George McCrae was their choice, or my son’s, but it was a shock at the service when their body was carried out to “You Can Have It All”.

Even though Angus wasn’t a ‘she’, our friendship retained a feminine quality. It’s cruel and potentially disastrous that they are no longer here so that I can ask them if it is okay to say this? All our conversations had a roomy quality, no topic was too taboo, what Maxine Kumin described in her poem for her best poet friend Anne Sexton after her suicide as:

a space we could be easy in, a kitchen place

with vodka and ice, our words like living meat.

Angus was patient with me when I admitted that as a former child raised by radical lesbians some of the new words were taking some getting used to for me. Even though I had read, and half understood Judith Butler in the 90s.

J said something else at the table. She remembered the metaphor exercise we had to do in the first year of our degree. I enjoyed this exercise much more than the camp, which I escaped after four hours using my blended family as an excuse.

Angus and J were in another group the day we presented to the class and J said that Angus used two opposing magnets as their prop and the bouncy strip of air between them as their metaphor, they want to touch, but a force stops them from touching. A force you can feel but not see and yet relies on attraction.

The purpose of a metaphor is transformative, it makes something fresh of the established, which Angus did every day, while also being conscientious and too considerate, until they could no longer be those things to everyone or use that courtesy to gloss over the void opening up inside them.

In a therapeutic sense, an issue must be worked through for a metaphor to be truly transformative, something double needs to be made of our suffering, a way out of the trouble presents itself as a luminescent fork in the dark. Angus made meaning out of everything that happened to them, good and bad, but struggled to recognise they were a real artist. The image of the magnets, unable to touch, despite a pull towards the other, was that simple, and true. It reeked of genius.

I knew that Angus was suffering, but I had also underestimated their ability to hide it. Even when I probed Gus at my table over coffee and it briefly blistered across their ahua, the moths that fluttered in front of their face disturbed by the things people, mostly men, had said to Gus to make them feel ugly inside. And it was frustrating Angus possessed no firm, constant grasp of how beautiful they were in the flesh, except in fleeting moments and their odd thirst post. It was impossible to ever really get Angus to see they were much more gifted than the person they were pouring their love into like unwanted cream. People have to see their worth for themselves.

It was not enough for Angus that they pulled so many other magnets around them, Angus couldn’t feel us in their shoulders beside them steel to steel, or how totally essential their existence was to ours. Real friends don’t care if you have red bloody stumps for feet and Angus was not one to shame a wound.

I am devastated and whakamā that I didn’t do more for them, even as I begin to assimilate the total wrongness of their death into something that doesn’t resemble blame. But I cannot comprehend it perversely because I understand too well their icy desperation. I was the same about love when I turned 28.

I will try not to be too forensically self-centred that I allowed Angus to break our pact because I was failing as a friend that week, lodged in my own crisis, and ignoring all the ruru, even when I don’t think of ruru as my spiritual problem. In my room I turned up the Stevie Nicks song I’d been listening to over and over when I heard a ruru hooting at me five times in the dark. We don’t get many ruru in this part of the valley. When my period arrived nearly a week early on a bitter Saturday morning, the first proper cold of the Winter, I was scared, I just didn’t know why. I thought what has happened now?

The night before I’d almost gone to see Angus to apologise for being koretake over the workshop, but I only had enough petrol to get to my Nana’s. The impressive vase of flowers on her table helped me remember she had turned 90 that day. The flowers were cream and mauve-brown roses cut with fat lilies. A bunch of subtle beauties that Angus would have loved.

After eyeing them, I told Nana that she has the same birthday as Judy Garland, and Kerry, my oldest friend. But I didn’t realise Gus was already over the rainbow.

Nana narrowed her eyes as I blathered on about her birthday and asked if I needed money?

The next day I’m crying over Gus in the carpark of Pak'nSave in my dressing gown, waiting with fogged up windows in the car as Nana follows my son around the supermarket making sure he buys the right things, food that will stretch, like mince and a sack of potatoes instead of the expensive coffee I’ve put on the list, which as a Mormon is alien to her. And it was then, that I thought of the most inappropriate song in the world for Gus. It didn’t come on the radio, that’s as broken as the air conditioning, it just started playing in the vents of my head.

It was “Hold On” by Wilson Phillips. A song I’ve never really listened to before because it used to be so ubiquitous and irritating. Now the lyrics started landing in me like lead sinkers. Wishing that Angus had held on for the delightful agony of just one more day.

Nana is taken to hospital later in the week after a fall. Turns out she had been staggering after my son in the supermarket with a fracture in her back. But not all of us take that much pleasure in being grimly determined to live. Although both Angus and Nana have, and had, their own, unshakeable version of the afterlife.

*

I’m not a hugger, I’ll strategise my way out of a hug days in advance, if I know a hug is coming, but almost every time Angus left my whare, or whichever place I was staying, I would hug them and say,

I love you, and they’d say, love you too.

Because I did love Angus, pretty much from that first ballgame, where their manners impressed me as much as their personal style, and I always will.

I was 43 when I learned the love of friends is enough to sustain me in this life. It’s the single tiny wisdom I possess, and I earned it only after feeling obliterated by romantic love. Sometimes I was too filthy for a hug with Angus, it was about me, not them. I would have asked Gus to bring me something like coffee or toilet paper and let them smoke all my smokes in return. They could get skittish. But their manners remained exquisite, to the point of pretending to like my kurī when I knew Gus found his habits and smells repulsive.

When I moved into this whare, Angus brought me a yellow welcome mat as a housewarming gift. It reads Kia Ora in black, because they knew I dread a knock at the door but that being seen as a welcoming Māori is important to me. In theory.

When I was in one of my more unstable situations, Angus came out to visit, I was back in my favourite inlet, Osborne, the most secret paradise in New Zealand. Me and Gus were having a spliff and splitting a bottle of pinot gris and a baby ruru flopped dead on the deck after being picked apart by sparrows in the air in front of us. It was an unusual event, but I wasn’t in the mood to admit it. I was sick-to-fucken-Māori-death of manu as tohu but Gus was fully into it. Just before their birthday and death they brought up the ruru and I was still tohu avoidant, but as a budding paranormal investigator Gus was always keen for any talk of omen and kehua.

And I said, it meant I shouldn’t have been there, staying in that house.

But it did not mean that. I should have listened closer to its crying in the dark. It was a message coming to me, not for me.

A couple of weeks after Angus died someone posted a photo of a kōtuku on Twitter. The white heron was making a rare appearance here, at the Dunedin Botanical Gardens, and of course, it made me think of Gus.

I ring Becky to tell her about it and she tells me about the ruru she buried at the Gardens, which her father found broken and cried over, and she couldn’t manage to save so she put it in the freezer with the tītī that later had to be defrosted and brought down south. So the ruru came too. I ring her again and threaten to dig up the ruru so I can deliver it at his door. But Becky can’t quite remember where she buried the ruru. She is a good Māori that way. I will find another way to whakanoa and drop this tapu off and set my shoulders free.

One of the only videos a friend of theirs shared on our private memorial page for Angus that I can bear to watch is of Gus at the Gardens holding a bag of bird food wearing their faux leather jacket. Pigeons keep landing on their head and shoulders and Angus is super accommodating to the pigeons, even as they invaded their space.

Oh apologies, Gus says. Then, God.

But the pigeons made mincemeat of the politeness that hid their true, strong spirit. Here was a safe person, full of love, disguised as murderous intent at any injustice, willing to let pigeons use them like a skyscraper. The video of Angus covered in pigeons finishes just as they say they are there to feed the ducks. I will have to go to the Gardens and feed the ordinary birds for you, e hoa, made as extraordinary by your memory as a peacock with all its accusing eyes for a tail. I remember you telling me what the peacock means to you. Our stupid, too bright fucken darling, I wish you had stayed so I could torture you with Wilson Phillips. I feel like you would get the joke and refuse to let anyone step all over you.

And you were so gorgeous e hoa, Jacob used to watch that soft face of yours while you slept. Love didn’t have to be a killing thing, there could still be a moment when we bump and do the hustle.

Aroha mai?

Āe.

That favourite affirmative word of yours.

A place where Angus will have to fit the cane peacock chair they left me into their waka.

Our Angus can fit anything into a sedan, even their wings.

Talia Marshall is guest editor of ReadingRoom this week. She has commissioned three articles on sexual, literary, and waitressing life in the 1980s by Emer Lyons, Becky Manawatu and Kelly Ana Morey.