Second only to writing the perfect song, it is perhaps the ultimate goal of any guitarist to forge a sound that is theirs alone. Duane Eddy, who died of cancer in April at the age of 86, certainly accomplished that.

And while the tag given to his methodology – ‘twang’ – had lightweight and frivolous connotations, the sound itself was anything but. “It’s a silly name,” the guitarist once said, “for a non‑silly thing.”

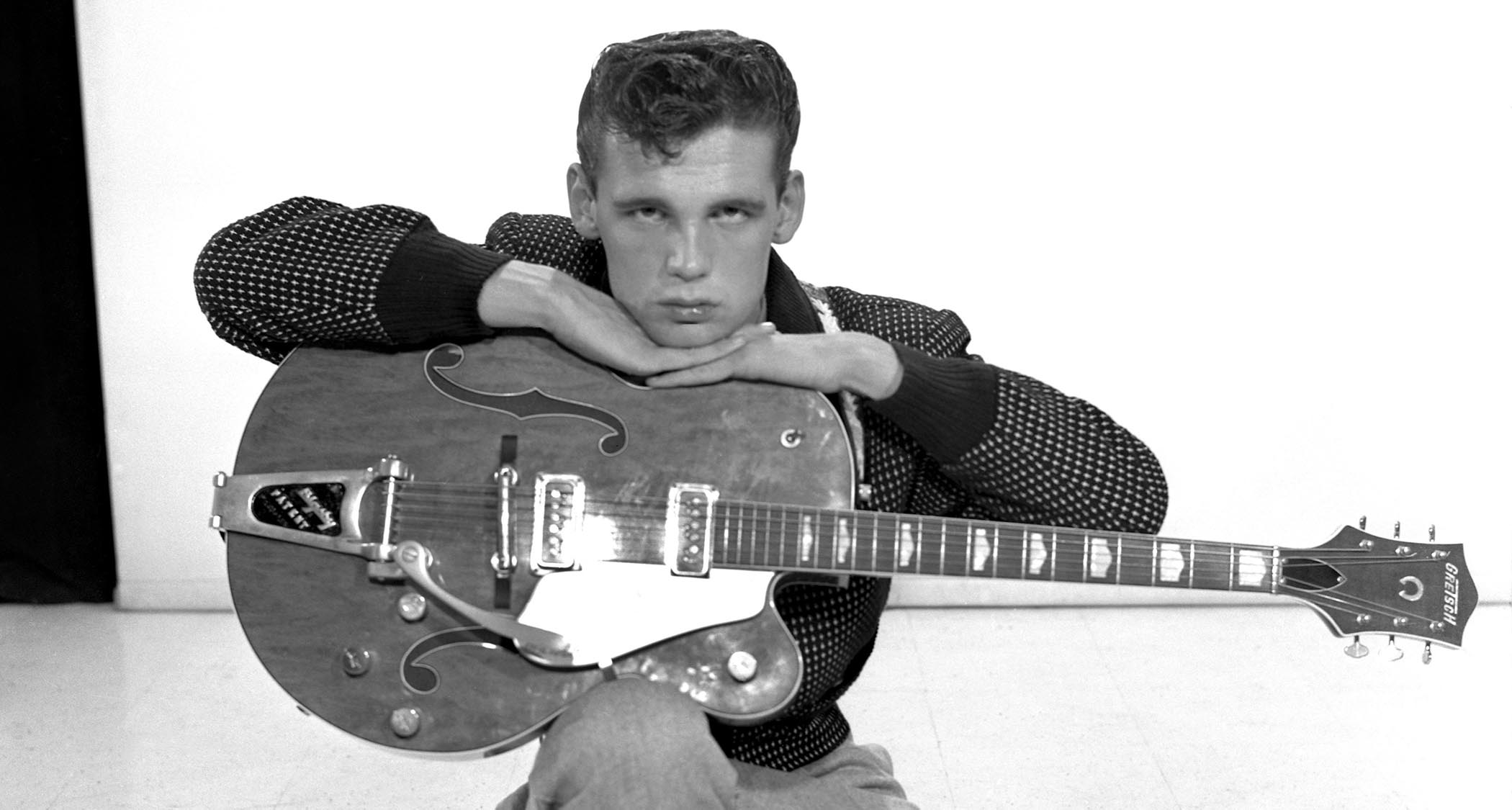

The low-slung, mysterious, otherworldly tone – played on the bass strings of his giant Gretsch archtop, clad in reverb and given a shiver by his Bigsby vibrato bar – made the US guitarist’s ocean-crossing instrumentals of the late-’50s so evocative that even life in suburban Britain felt like a classic American movie.

As the essayist Michael Hill wrote when, decades later, Eddy was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: “Twang came to represent a walk on the wild side… the sound of revved-up hot-rods, of rebels with or without a cause, an echo of the Wild West on the frontier of rock ’n’ roll.”

Yet that illicit sound began with a flash of pure childhood innocence. Born in 1938 in Corning, New York, Eddy caught sight of the instrument for the first time at five years old when the family moved house.

“We were down in the cellar and up against the wall was leaning a guitar,” he told this writer in 2010. “My dad showed me a few chords he’d used for courting my mother. And I just fell in love with it.”

Playing along with country records on the radio, then swerving into rock ’n’ roll after the epiphany of an Elvis concert, Eddy realised that “in some way, I’d have to do that”. His high school years in Arizona were a parallel existence, with Eddy studying by day then gigging the local clubs by night.

But, at the age of 16, he bet the house on a music career, and shortly after came into the orbit of the established DJ, music publisher and songwriter Lee Hazlewood, who impressed Eddy with the fact he had co-written and produced Sanford Clark’s 1956 hit The Fool.

Together, the pair wrote and recorded 1958’s Moovin’ And Groovin’: an irrepressible dancefloor-ready stomper, with Eddy’s seismic pluck already in place, thanks to his philosophy that “the low strings were more meaty-sounding”, the use of a modded Magnatone and the recent acquisition of a Gretsch Chet Atkins 6120.

“I started out with a Gibson Goldtop in 1954,” Eddy told Total Guitar in 2011. “But it didn’t have a Bigsby vibrato, so I walked into a music store one day and the guy showed me a $450 Gretsch.

“It just nestled in my arms perfectly. The neck was a dream and it had a Bigsby. The guy gave me $65 for my Gibson and let me walk away with the Gretsch, even though I wasn’t old enough to sign the papers for the loan. Those were the days!”

Think tank

Just as important was Hazlewood’s production masterstroke. In those early years, with echo chambers still a rarity outside the major cities, the veteran took a novel approach to the limitations of Phoenix’s Audio Recorders.

“Our echo chamber was actually a 2,000-gallon water tank,” Eddy told Guitarist in 2019. “We went down to a Salt River junkyard and yelled into tanks that might work as a reverb chamber. Lee would go, ‘Whoop!’ and he got an echo out of them. He finally found one that he yelled into and he liked the echo, so they bought it for a couple of hundred bucks and trucked it up to the back of the studio.”

Eddy credited Elvis Presley for opening the door – “He came along and showed us how to do it” – but the guitarist followed him through in the late 50s with a markedly different approach.

Eschewing vocals in order to stand out from the pack, Eddy’s album titles set out his modus operandi, often by way of a slightly laboured pun. Have ‘Twangy’ Guitar Will Travel (1958). The “Twangs” The “Thang” (1959). $1,000,000 Worth Of Twang (1960). Twistin’ ’N’ Twangin’ (1962). “Twangin’” Up A Storm! (1963). The Biggest Twang Of All (1966).

Drop the needle on these records and the song formats were often similar, with Eddy’s wiry lick typically kicking things off before a jangled acoustic rhythm guitar, handclaps and howling brass enter the fray.

“I kept those melodies simple,” he told Classic Rock magazine. “A guy can pick up a guitar and play the first notes of Rebel-Rouser or Peter Gunn. Then you’re encouraged to go, ‘I might be able to do this.’”

On both sides of the Atlantic, many future greats did just that. “When I was 12, I remember hearing Moovin’ And Groovin’,” Creedence Clearwater Revival’s John Fogerty told Rolling Stone. “It was unlike any other guitar I’d ever heard. It had this wonderful, huge, big sound, then he started twanging the strings. The sound was massive, the tone was perfect. Where he placed the notes made so much sense.”

“He was my first guitar idol with songs like Rebel-Rouser, Shazam! and Some Kinda Earthquake,” added Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore upon the news of Eddy’s death.

“I would always rush out and buy his long-playing records. My favourite all-time tune from him was The Lonely One. He was a brilliant guitarist in his own right. He was the first guitar player with that deep bass sound, which I loved.”

Top Gunn

At the turn of the decade, Eddy seemed unassailable. NME crowned the American as World Musical Personality and Melody Maker declared him “the first real guitar superstar of the rock ’n’ roll age”, while he was notable as the first rock ’n’ roller honoured with a signature model, in the form of the Guild DE-400 and DE-500.

Between 1958 and 1963, no fewer than 16 of Eddy’s singles charted in the Top 40, including the aforementioned Rebel-Rouser and Shazam!, plus Ramrod, Cannonball, Forty Miles Of Bad Road, Because They’re Young and, perhaps most famous, 1959’s Peter Gunn, his loping interpretation of Henry Mancini’s detective-show theme tune.

“We had 11 songs and Lee came out of the booth and said, ‘Well, what are we going to do for the 12th?’” Eddy recalled in Classic Rock. “So we did Peter Gunn – and it got to rocking. We finished this one take and we were breathing hard. We were playing so hard, just driving the stuffings out of it.”

All the while, Eddy’s work left its mark on the guitarists who followed on his heels. Revisit the languid phrases of Hank Marvin in The Shadows, or the brittle riff that opens The Beatles’ Day Tripper, then move onward through Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run, Blondie’s Atomic, Chris Isaak’s Wicked Game and even the fathoms-deep pulse of Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks theme. Eddy’s approach – with its ghostly shimmer and acres of space – looms over them all.

We did Peter Gunn – and it got to rocking. We finished this one take and we were breathing hard. We were playing so hard, just driving the stuffings out of it

A more litigious songwriter might have angled for royalties. Yet Eddy was sanguine about hearing his influence (“This is not a competition,” he shrugged. “We help each other”) and gracious when another act borrowed a little too brazenly.

He insisted the heavily indebted Marvin “did it in his own way”, and even endorsed The Beach Boys’ lift of his Moovin’ and Groovin’ lick for 1963’s Surfin’ USA. “I was honoured and glad they borrowed it,” Eddy told Total Guitar. “It was like, ‘You wanna borrow this jacket for your show? Go ahead!’”

Yet the new wave of bands who revered Eddy also inadvertently sounded his career death knell (at least for now).

“In 1960, the charts in England were 95 per cent American, five per cent British,” he told Classic Rock. “I went back at the end of ’63, and it was the opposite. And I thought, ‘Well, they’re getting their own back.’ When The Beatles hit here, it died off for me. I’d had my five-year run, and I didn’t get upset about it. I thought, ‘Well, they can take it from here…’”

By the late ’60s, Eddy had stepped back – or perhaps been pushed – from frontline action and worked more commonly on production or session work. But the ’70s rockabilly revival led listeners back to his classic material, before his 1986 collaboration with synth group Art of Noise birthed a UK Top 10 and Grammy-winning reboot of Peter Gunn.

“I was worried that all my old fans, the ‘purists’, would hate the record,” Eddy told Blitz, “but they’ve taken to it like a duck to water.”

One of a kind

In the ’90s, Eddy’s songs were regulars on movie soundtracks, with Rebel-Rouser featured as a carful of greasers try to plough down Forrest Gump, and his dust-blown Ravi Shankar collaboration, The Trembler, heard in video-nasty Natural Born Killers.

The guitarist rode that renewed profile all the way to the end. In 2017, The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach invited Eddy to guest on his Waiting on a Song album, and when this avowed Anglophile returned to the UK in 2018 to play three rare dates, Richard Hawley led the backup band.

“What a unique thing he created. Without singing a note in his entire life – what a voice,” said the Sheffield guitarist, who also co-produced Eddy’s final studio release, 2011’s Road Trip.

“Duane sold 200 million albums, and he was the coolest guy. He was gentle and kind and all the things that you should be as a human being.”

Indeed, while Eddy’s music will be his chief legacy, it should also be noted what a decent, modest and good-humoured man he was. This writer remembers gaping as the trailblazing musician dismissed his career milestones as a “series of accidents”, and joked that he had managed only “10 per cent” of Elvis’s record sales.

Far from believing the column inches proclaiming him a pioneer, Eddy once insisted his greatest contribution to music had been “not singing”.

In 2018 came the first hints of trouble, as Eddy spoke of “overcoming a couple of medical issues”. Even then, the guitarist insisted he couldn’t “get my mind around” entering his ninth decade, and his youthful demeanour meant it was a jolt to learn of his passing at Tennessee’s Williamson Health Hospital, just days after his 86th birthday.

“I’m in shock,” wrote Dave Davies of The Kinks. “Duane Eddy was one of my most important influences. I thought he’d live forever.”

The ’50s’ originators are almost gone now, and we will not see their like again. Yet while that mighty Gretsch might have fallen silent, the acolytes of the Sultan of Twang will carry his sound forever onward.

“Rest in peace, Duane Eddy,” wrote Joe Bonamassa, alongside a photo of the master’s signature model. “A true pioneer and bona fide legend.”