It was when Danny Fitzsimons hid in a wheelie bin that his family began to suspect something was wrong. Danny, 34, had been drunk and abusive at a family event, circling the house and banging on the windows. “Every now and again, the bin lid came up a tiny bit and then went down again,” says his stepmother, Liz.

She looks at Fitzsimons’ father, Eric, who has since developed dementia. We are sitting in the living room of their smart bungalow just outside Rochdale; they are both retired, former PE teachers. “Eric said, ‘Come on, Danny, I’ll take you home’ and he said no. So Eric waited till Danny set off, and thought he’d better make sure he got home. Eric didn’t get back till 3am. I said, ‘Where have you been?’ He said, ‘I’ve been following Danny. He’s been playing bloody soldiers all the way home.’ He was doubling back, hiding behind walls. We now know that this is hyper-vigilance, but we didn’t at the time.”

Fitzsimons had joined up at 16, excelled in training, saw active service in Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq, and won a distinction as a sniper. In 2004, after eight years, he applied to have his contract extended, but was discharged. “They said he had anxiety disorder,” Liz says. What did the army do to treat it? “Nothing that I’m aware of.”

When he returned home, Fitzsimons was a different character. He had gone into the army full of hope (his mantra was the Farm song All Together Now) and came out full of hate. Liz recalls a time when he was left with his younger cousins. “He said to the kids, ‘This is what you do to niggers: get them on the floor and stamp on their head.’” Where had that come from? “The army, I think. He wasn’t racist when he went in.”

Fitzsimons began to get in trouble with the law. He served nine months in prison for assault (his defence was that he thought he was being followed), was convicted for firing a flare gun over the heads of teenagers climbing on his roof, and was charged with a racist assault.

In May 2008, he was diagnosed with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by a court-appointed doctor. In June 2009, Dr Jameel Hussain wrote a psychiatric report, in which he said of Fitzsimons: “He gave a clear description of nightmares, vivid dreams, visual flashbacks, and he can also smell burnt flesh and feel the smell of death… At times he would be afraid to sleep because of the nightmares he was having. He also described… an example of tensing up when he saw hazard warning lights on a vehicle. He explained that in Iraq, vehicles loaded with explosive devices only had their hazard warning lights on.”

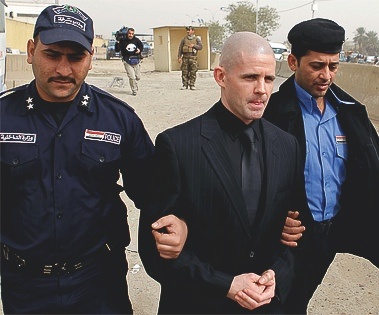

When Fitzsimons applied for a job in Iraq with the security firm Armour Group Security, owned by G4S, he didn’t tell his family. At the time, he was on bail and not allowed out of the UK. Somehow, none of this was enough to deter G4S from employing him, in August 2009. He had been in Iraq for just 36 hours when he shot dead two colleagues, Scottish security guard Paul McGuigan and Australian Darren Hoare, after a night of heavy drinking. Fitzsimons claimed it was self-defence, but he was convicted of the two murders and sentenced to 20 years in jail, in Iraq. It emerged that G4S had not checked his records.

Liz is desperate to bring Danny home to a British prison. She shows us photographs of him as a giddy young boy, as a proud paratrooper, and letters in which he talks about how well he’s doing in training. Then more disturbing letters, in which he talks about the horrific things he’s seen. Liz describes how they heard about what he did, and it’s as if she’s telling it for the first time. “Danny’s friend, Scott, texted Eric and said, ‘I think Danny’s in trouble in Iraq.’ We didn’t even know he’d gone to bloody Iraq. Scott said he thought Danny had killed somebody. I rang Rochdale police and they said, ‘Ring the police in London’, and when the copper rang back, he said, ‘Look at the front page of the Washington Post’, and there it was.”

Liz blames a military that dismissed Fitzsimons with no follow-up, and a security company that failed to do basic checks. “I rang the army because I wanted to know what to do, and they never even answered me.” Fitzsimons was haunted by a recurring image, Liz says. “He was only 18 or 19; he was out on a tour in Kosovo and this little boy, six or seven, would bring them bread and milk. They played football with him and would chat with him, and one day they found the little boy’s body in pieces in their water supply. Imagine how you cope with that? They knew it was their fault, because the boy was seen as a collaborator.”

Both the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Justice agree: there are a worrying number of veterans within the criminal justice system. MoD statistics err on the conservative side, quoting 2,820 veterans in prison in 2009/2010, or around 3.5% of the prison population. In 2009, the National Association of Probation Officers (Napo) put the figures higher: 8,500 veterans serving sentences in UK prisons, and a further 11,500 on probation or parole. Two out of three ex-soldiers imprisoned in the UK have committed sexual, violent or drug-related crimes, according to the MoD. The research into the relationship between ex-soldiers’ PTSD and crime is inconclusive and often contradictory: a Howard League for Penal Reform inquiry in 2011 concluded that there was no link; a Napo report suggested that half of veterans in prison had depression or PTSD (compared with 23% of the male prison population).

“It suits the MoD to minimise the numbers in order to reduce the extent of liability,” says Tony Gauvain, a retired colonel, psychotherapist and chairman of the charity PTSD Resolution. “But given the numbers of people suffering symptoms now, and the latency of the condition likely to result in increasing numbers, there would seem to be a determination to avoid admitting there is a problem.”

The idea that PTSD can lead to violent crime is embarrassing for the MoD – and potentially costly. Those diagnosed with combat-related PTSD are entitled to a disablement pension, while victims of the crime could also potentially claim compensation. Between 2005 and March 2014, 1,390 claims were awarded under the Armed Forces and Reserve Forces Compensation Scheme for mental disorders (including PTSD) – but this figure could well spiral over the next few years as the army withdraws from Iraq and Afghanistan. To put this into context, in America, 20% of veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq have been diagnosed with PTSD; in 2011, 476,514 veterans were treated for it.

Robert Kilgour scares his family, and he often scares himself. He has been imprisoned three times for violent offences. On the last occasion, he almost killed a man – his victim required 100 stitches after Kilgour attacked him with a bottle. We meet at his flat in Edgware, north London. On a table is a photograph of his former wife and his family. Kilgour is tense, on edge. He served in Northern Ireland, Bosnia and the Gulf war, and returned to civilian life in 1993. But everything was different. “I just couldn’t keep it under control. I don’t want nobody to be close to me. I don’t want them to see what I’m going through. I’m 43, and every time I think about what I’ve gone through, it brings it back. It’s still raw. I’ve seen some of the best people you’ll ever meet in life put in the ground, and I’ve put people in the ground. It’s changed me.”

Kilgour says some members of his family disown own him – they tell people he’s dead. In a way, Kilgour says, they are right – he is dead, or at least the young boy who dreamed of being a boxer is dead. He doesn’t act, or react, like a rational man. He frequently gets into fights. “I don’t like no one. I don’t even like myself. I’m disgusted with some of the things I’ve done. You take someone’s life away, no matter if he’s going to kill you, and you don’t ever get over it.”

He talks about his nightmares; the screaming, the shaking, the sweating. What does he dream about? “That’s a bit personal, as it happens.” Silence. “No, I’m not going to shy away from nothing. Listen, if this helps anyone...” He stops again. “Mate, if I drop a tear and you laugh at me, I’m going to smack you straight in your fucking face, I swear.

“My best mate Rob was from Norfolk, and we were in Fermanagh, in Northern Ireland. I was the lead in a four-man team, and my mate got shot in front of me. He was ripped apart. He looked like a lump of meat. I didn’t even know who it was. I just looked down and carried on firing. That’s my recurring dream. I was going to be his best man. He was supposed to be married the following week. I had to go up to Norfolk to see his missus. She said, ‘You said you’d look after him.’ And she slapped me round the face.” He laughs, but a strangled sound comes out. “I was crying my eyes out, and she wouldn’t even let me in the door.” Does he ever wish he had been the one killed? “So many times.”

Bluebell, his jack russell, starts barking. He jumps. “I’m very on point all the time. Anything that happens, the slightest noise, I’m like that. I’ve got a couple of friends going through this, and they’re doing lithium. They can’t look straight at me – they’re dribbling wrecks.”

Rob was killed 20 years ago, but Kilgour didn’t begin to process his death until he started getting arrested repeatedly for violent assault. He says it was only when he was in prison that he found out what was wrong with him. “It took a prison officer, an ex-army bod, to come to my cell and say, ‘I know you’re suffering.’ Before that, I just thought it was me. I’m still having counselling eight years on.”

After his release, he received counselling from PTSD Resolution. Kilgour blames the army for failing to prepare him for life on the outside. “That’s why so many of my colleagues go to prison. It’s all due to violence. None of them can keep a relationship.”

It’s mid-afternoon, and he cracks open a can of cider. He says he’s controlled his drinking these days. “I used to drink till I went to sleep. I just wanted blackness. It was like a form of dying.” Since he started counselling, he’s been in trouble a few times, but he has not been in prison again. He has no trouble finding work as a roofer, but still misses the camaraderie of the army, the sense of purpose and order in his life.

“24795536 Private Kilgour, third battalion Queen’s Regiment, sir! You go there,” he says, “you stick a bayonet in and stick a couple of rounds in someone’s head. I’m signing off now. Right, fuck off. They trained you to be a soldier, a killer, but they don’t then train you to be a civilian again. I’ve done so much for you and you took so much away from me. Why don’t you just give me a little bit back? Why don’t you give us six months and retrain us?”

More service personnel are returning to civilian life. What is the army doing to prepare them for it? “Nothing,” he says. “You’ve only got a few centres round the country looking after people suffering from combat conditions. I guarantee you, in the next five years you’ll hear so many things: an ex-serviceman killed his missus; an ex-serviceman killed two people. It scares me.”

***

Combat Stress HQ in Surrey exudes calm, with its manicured lawns and ex-military personnel quietly going about their business. It is by far the UK’s largest mental health charity for armed services veterans. Dr Walter Busuttil, its director of medical services, admits that the MoD has been reluctant, in the past, to recognise PTSD. “Do you know much about the class action held against the MoD in the late 1990s?” he asks. “OK. There was an allegation from Falklands veterans that the military could and should have treated post-traumatic stress disorder. About 400 took the MoD to court, and they lost their class action, but many of them won their cases on an individual basis. After that, the MoD took steps to make sure that didn’t really happen again. So it decided to do much more research, which is why the King’s Centre for Military Health Research (KCMHR) in London came about.”

Research carried out at the KCMHR has shown that army personnel experiencing “mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder” are 4.8 times more likely to report violence on homecoming. What is Busuttil’s experience of combat-related PTSD?

“The main thing I hear is, ‘I was a bit more irritable when I came back from deployment. I became irritable years later. I lost my temper, I started drinking a bit more. Couldn’t sleep… nightmares about military service.’ Then specific incidents, particularly worrying about being in a crowd. So it’s about feeling hemmed in, irritability and excessive drinking.”

Busuttil insists it is simplistic to assume a direct correlation between PTSD and violent crime. “There’s an element of self-selection: a lot of these men had been violent before they joined the army. You don’t have to become ill to be angry.” He is convinced that alcohol is the dominant trigger. But surely, if you’ve got PTSD, you’re more likely to drink? “Absolutely. And combat in itself makes you more aggressive.”

Busuttil agrees that the armed services could do more to prepare veterans for civilian life. “We need to look closely at how we manage the transition. It’s difficult to engage people at the end of their service – it has to be a managed process from the day they join.”

On our way out, the Combat Stress press officer asks for a word: don’t forget, he says, that most veterans make a perfectly successful return to civilian life. “We focus on the extreme cases here, but about 20,000 people leave the armed forces every year. Many people make that transition.”

***

At the King’s Centre for Military Health Research in London, forensic psychiatrist and clinical lecturer Dr Deirdre MacManus conducted a study of 4,928 UK armed forces personnel deployed in Iraq in 2003. The study found that 12.6% admitted to being violent on their return home, and that the violence was often associated with flashbacks to experiences of combat and trauma. In many cases, the violence expressed itself years after combat.

Like Busuttil, MacManus believes that alcohol and background play a major role. “Yes, PTSD is strongly associated with violence, but the caveat is that it’s not as prevalent as other problems, such as alcohol misuse, which again is a strong predictor of violent offending.”

She mentions the low MoD figure for PTSD among UK veterans (3.5%), though she admits that the figure rises to 7% among those who have seen active service. As of September 2011, at least 191,000 soldiers have been deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, so even by MacManus’s estimate, in the next decade or so there could be more than 13,000 ex-service personnel returning from combat zones with mental health problems. The question of whether they are diagnosed and how they are treated will become critical.

McManus says military personnel can become fixated with PTSD in a way that isn’t helpful. “It’s almost like a badge of bravery. If you have PTSD, then it’s related to combat. If you have depression and anxiety, well, anybody can get that. I think that’s unfortunate, because I see guys coming to me suffering terribly with social anxiety, or depression, but if I give them that diagnosis, they are like, ‘Hang on, doc, are you telling me I’ve not got PTSD?’ They’re not happy to be told it’s ‘just’ anxiety, and won’t engage in treatment.”

Rather than concentrate on the numbers of veterans in the prison system, MacManus says we should look at it the other way round. “A lot of those who join up do a lot better [in life] as a result of being in the military. We focus on the negative outcome, but the military employs a lot of people who perhaps no other employer would touch. We know that, among the cohort who enter basic training, there’s a high level of deficits in reading and writing ability. And they’re probably some of those who do very well as a result of joining the military.”

In March this year, about 100 specialists gathered at Portcullis House, opposite the Houses of Parliament, to launch a review into the number of veterans caught up in the criminal justice system. The review was set up by justice minister Chris Grayling and chaired by Conservative MP Rory Stewart (who has had to stand down since he was elected chair of the defence select committee). Impressive papers were read by experts, pointing to multiple issues: a lack of jobs, housing, discipline, training for civilian life; disadvantaged backgrounds; reliance on alcohol and drugs; alienation; unpopular wars; “decompression time”, in which armed forces personnel are given 24-48 hours to get drunk in Cyprus before being returned to civilian life. They discussed the possibility of special military courts, such as those introduced in the US; acknowledged that many veterans don’t admit they were in the armed forces because they feel they have brought shame on the military; and examined ways in which veterans who offend can be identified early.

The discussion was relevant and well-meaning, but PTSD was not a high priority among the topics raised, and experts representing veterans suffering from combat-related PTSD seemed sceptical. “I think it’s going to be another whitewash,” Aly Renwick of Veterans in Prison told us.

Renwick was there to champion the case of Jimmy Johnson, who is serving a life sentence for two murders. Johnson has spent the past 29 years in Frankland maximum security prison in Durham, serving his second life sentence. He left the army in 1973 after 10 years’ exemplary service. He had been “mentioned in dispatches” for a heroic attempt to save a woman bombed in an underground toilet, but was traumatised by what he saw (“She looked like a large rag doll smashed to pieces”). He never recovered, and bought himself out of the army. He struggled to find work, became depressed and began to drink.

Four months after he signed his discharge papers, he accepted a lift in a van from an acquaintance. The driver slowed down to pass a group of children playing football. There was a loud bang – either the ball being kicked against the van or a brick being thrown – and Johnson flipped. He remembers taking hold of his acquaintance by the arm and neck. What he doesn’t remember is grabbing a scaffold pole and beating him to death with it. He served nine years. Eighteen months after his release, he killed another man, beating him to death with a lump hammer. Again, he remembered little more than that he’d done it.

While he was in prison, another inmate, a former doctor, told him he could have PTSD. For many years Johnson has campaigned for greater awareness of the condition within prison. In 1990, he set up the first veterans’ therapy group in the UK prison system, and later wrote a Veterans in Prison handbook: a survival guide for those with PTSD. Writing to the Guardian from Frankland, Johnson says that many veterans are unaware that their experience in combat may have left them with mental health problems, which then go ignored and untreated.

Johnson contributed a written piece to this year’s review of veterans within the criminal justice system, citing evidence he collated for a 2007 Veterans in Prison survey: out of 120 inmates he interviewed, 12 were ex-servicemen, 10 of whom had served in conflicts. All 10 were serving life sentences for murder.

Johnson said the British criminal justice system should learn from the US, where veterans who are arrested are put through a different legal process, and also given access to psychiatrists, psychologists and lawyers who specialise in combat-related PTSD. Some are tried at a specialist veterans’ court, and defence teams can plead mitigating circumstances.

Johnson acknowledged that PTSD can be used by veterans as an excuse for their crime – indeed, there are those who would say Johnson is doing just that – but, he claims, by far the greater risk is that PTSD goes untreated throughout a prison sentence. In his evidence to the review, he wrote: “Shamefully, veterans of war/conflicts have been totally disregarded by the criminal justice system, and conveniently all classed as criminal in the prison population. Terrifyingly, this means that over the years substantial numbers of ex-soldiers who have served life sentences for murder have been released back into the community, the same as they were when they returned home from serving in wars/conflicts … ticking timebombs.”

The MoJ insists it does its best, encouraging prisons to identify former armed forces personnel, then providing access to mental health teams and armed forces charities. Perhaps a measure of their success is that most of the men interviewed for this article were diagnosed while in prison.

When asked whether under-diagnosis of combat-related PTSD by the armed forces and related organisations might lead to a rise in dangerous behaviour, the MoD responded: “We are committed to providing our armed forces personnel and veterans with all the support they need. That is why this government is investing £7.4m [since 2013] to improve mental health services available to veterans and is running campaigns to encourage more of our troops to come forward and seek help. In addition, all personnel undergo a full assessment before leaving the armed forces. If any mental health issues are identified, those individuals are offered further support and continued access to specialist services even after they have left.”

***

Last September, army reservist corporal Harry Killick, who had served in Afghanistan, was jailed after admitting to stealing a rifle and ammunition from his barracks in Brighton. In October 2012, he had turned up at the house of his former girlfriend, Jackie Lothian, and entered the property with a fully-automatic weapon and a round of live ammunition. She was not there, but her brother Jason was. Killick loaded a round of ammunition in front of him and asked where his sister was, but Jason managed to call the police. Killick, who was £20,000 in debt, claimed that he had planned to kill himself. After he pleaded guilty, citing trauma suffered during his tour in mitigation, sentencing was adjourned while judge Anthony Scott-Gall considered non-custodial options.

But then the army produced documents to undermine Killick’s case. It stated that Killick had not witnessed colleagues being killed or injured in Afghanistan. The army added that none of the contacts Killick had endured in his six-month tour was “particularly fierce”, that his sergeant had given him a glowing reference, and that “at no stage has there ever been any suspicion or suggestion that he might be suffering from PTSD as a result of his experiences in Afghanistan”.

Judge Scott-Gall branded Killick a liar, saying he had been accurate and truthful in many areas, but in the critical areas, he was not. He ruled that Killick was suffering from adjustment disorder rather than PTSD, and sentenced him to five years in jail.

In May, Killick wrote to the Guardian from HMP Highdown in Sutton, saying he was involved in 300 foot patrols, two of which involved contact with the enemy, and described his anxiety after an IED exploded, injuring one of his company. When he returned to his parent unit in the UK, he says his behaviour changed dramatically. “I had issues with noise, shouting. I could not watch programmes on television and I was constantly having flashbacks. Before this tour I had prided myself on being level-headed, able to deal with pressure very well.”

Killick recognises a gradual build-up to his theft of the gun. “I had issues not long after returning, but did not know why. On 12 June, after someone had a go at me about Afghanistan, I just lost it. I just popped. Everything that happened came out. It was like every memory I had came up and up and would not go away. Day by day, it got worse until I could not sleep, concentrate, lost interest in things…”

It is documented that on Killick’s return he asked the army for trauma risk management assessment and was seen on three occasions by a community psychiatric nurse. “During August, it got so bad I made my first attempt of suicide, but was talked down by my sister. I reported this to the mental health nurse on his next visit and a more in-depth assessment was done. I was then referred to the local mental hospital to see a psychiatrist, but I never got to see him because I was arrested.”

Since being in prison, Killick has been assessed by psychiatrists from the prison health care team and been diagnosed with PTSD. He hopes to appeal his five-year sentence through the Criminal Cases Review Commission, and says he cannot understand why the army was so determined to deny that combat-related PTSD contributed to his crime.

***

Walter Lee spent 23 years in the army, serving in Northern Ireland, Cyprus and Kenya, and during his final four years worked as a boxing coach with the King’s Regiment. Last year, he was medically discharged with diabetes. He had difficulties adapting to civilian life. He got drunk and mouthy one night, and ended up in a police cell.

There are many charities working with veterans struggling to adapt to life on the outside – some more effective than others. One of the better organisations is Live at Ease, which provides support for veterans within the criminal justice system. After he was arrested, Lee was contacted by a senior veterans manager, Alan Lilly, who asked if he was having problems with life on the outside. “So I’m like, ‘Alan, honestly, I got a bit drunk, I was cheeky to the police. But I came out with a pension, I’ve got a house and a job.’”

Lee felt he’d got off lightly, but he knew that some of his former colleagues had got into serious trouble. He decided to volunteer with Live at Ease. However, Lee was in more trouble than he liked to admit. He spent all his money on his daughter, lost his job and discovered he did have anger issues. The more you talk to Lee, the more you realise he is one of those veterans Jimmy Johnson was talking about: adamant that they have not suffered combat-related PTSD, despite the evidence mounting around them.

Lee explains why he joined the army. “I was getting in trouble when I was younger. I was hanging around with the wrong people. I never thought about the army until one of my mates joined – Stephen, my best friend. He’s dead now. A group of us go to Liverpool every October. We all meet up for five friends who got killed in Ireland. We have a guest speaker, a band, the drummers come on.”

The incident happened in 1990. A van drove into a checkpoint and detonated a 1,000lb bomb as Lee’s friends were getting into an armoured Land Rover. “The only reason the guys who survived did so was because the doors imploded and jammed instead of exploding outwards. A team of IRA came down from the hill to kill the survivors, but they couldn’t get in because the doors had jammed. As we were trying to get out we could hear our friends saying, ‘They’re trying to get in.’ So that’s a harrowing story, yeah.”

Lee left the army later that year. “I was diagnosed as acute death-phobic. I just learned to deal with it, with the anxiety and stuff that goes with it.” But he’s just said he has never had a combat-related stress condition. He laughs. “I’m fine now, I’m fine. And it’s good to talk about it.” How did the acute death phobia express itself? “I had hot sweats. I used to wake up in the middle of the night. I don’t class it as acute death-phobia any more. I threw away the tablets.”

He rejoined the army in 1994, stayed the best part of 20 years and loved it. “I miss the camaraderie, the discipline, the routine.” But like Robert Kilgour, he feels bitterness towards his former employer. “It’s a lonely life; once you’re out, you’re on your own. Basically, you’re institutionalised.”

***

“These were not cries for help, this was serious,” Elizabeth Powles says of her husband, Barry. “He’d use a blade. If I walk away, he will self-harm. It’s as if he has been possessed.”

Elizabeth is talking from her home in Exeter. Her husband, Captain Barry Powles, served 32 years in the parachute regiment; he saw active service in Malaya, Borneo, Bahrain, Yemen and several tours in Northern Ireland. He is currently sectioned at the Langdon hospital for the mentally ill in Dawlish. In June 2013, the former paratrooper was sentenced to 12 weeks in prison for common assault on his wife.

Elizabeth insists he did not actually attack her. She says she had a seizure and blacked out. While she was unconscious, Barry stabbed himself in the hand. He then started stacking furniture compulsively. Elizabeth says that when she came to, there was blood everywhere. She banged into the furniture, which collapsed on her. Her husband was later arrested and convicted of assault. He was diagnosed with combat-related PTSD by two psychologists and two psychiatrists. Just three days after he came home, there was another incident. This time, Elizabeth says, he really did assault her. “I went to wake him up and he just reared out of bed and went for me. It was as if I was attacking him and he was defending himself. It didn’t seem like my husband. I think he was having one of his night terrors.”

In June 2013, Powles pleaded guilty to grievous bodily harm and was remanded to Exeter prison, where he spent 10 months before being transferred to the psychiatric hospital. Elizabeth and Barry have been married almost 51 years, and she says he has been having nightmares ever since she knew him. Did he have treatment? No, of course not, she says. He was too proud, too private, and who knew about combat-related PTSD in those days? “In the army, you don’t show anything, not in front of your mates.”

Despite his problems, Elizabeth says, she could not have wished for a better husband. “I know it might sound awful coming off a pair of old wrinklies, but we’re two halves of a coin.”

Powles had never been much of a drinker in the army, but he started to drink secretly after he retired, hiding alcohol in the garage. His assaults were judged to be alcohol-fuelled, but his wife is convinced it’s the other way round: that her husband was drinking because he couldn’t bear living with his condition.

Eventually, Elizabeth forced him to confront his problem and he got in touch with Combat Stress. A case worker was initially helpful, but then said she would work with Powles only if he stopped drinking. Elizabeth still finds this baffling. “Combat Stress will not recognise that drink is part of the self-medication. It’s no good saying, ‘If you have another drink, I shan’t come back.’ That’s not treating it at all. It’s ignoring it.”

Last October, Elizabeth received a letter from the Service Personnel and Veterans’ Agency (the MoD’s pension body), which stated that Powles was due only a 60% war disablement pension because Combat Stress “were not supportive” of the PTSD diagnosis. This August, following an independent diagnosis of service-related PTSD, the agency revised this, writing to say the pension had been increased to 100%.

Powles has no memory of the attack. The judge delayed sentencing, and he was sent from prison to Langdon. The hospital is a sterile, soulless, modern unit and, visiting on a warm day, it’s a relief to escape to the garden outside. A short, wiry man with luminous hazel eyes and a strong Midlands accent, Powles talks of his time in the parachute regiment, proud of his progress through the ranks, from private to captain. When he was in Borneo, his unit was sent to search for three missing soldiers from the Royal Signals. All they found were bodies, two half-eaten by animals and another decomposing, hanging from a tree. He was later sent to Yemen to search for two more soldiers – this time, all they recovered were two severed heads that had been paraded round a village on stakes, to frighten the locals.

Then, visibly upset, he tells of a duty he undertook when he was finished with active service. During the Falklands war, it fell to him and his commanding officer to inform service wives that their husbands had been killed in the conflict. “The rule was, we had to wear full ceremonial dress to visit the army housing estate. When the women saw us coming, some refused to open the door, refused to believe the message they clearly knew was being delivered.” This memory seems to haunt him even more deeply than the gruesome scenes he witnessed in conflict zones. “I never thought about the things I’d seen while I was serving. I was too busy. Then I started to think and have flashbacks, and drinking was a hiding place.” Today he seems calm, and says he wants nothing more than to pick up the pieces of his life with Elizabeth.

A couple of weeks after our visit, Powles is finally sentenced to 24 months in jail and released on licence, because he has served more than half his time. But the judge insists that Powles must live in a hostel in Plymouth until November 2015 and have no contact with Elizabeth. She is distraught and convinced that his mental health is deteriorating.

The findings of the government review into veterans in the criminal justice system is due soon. The former soldiers we spoke to, and their families, fear a report that will understate combat-related PTSD as a contributory factor. They question whether the army and Combat Stress are being sufficiently vigilant, and wonder why many of the former soldiers affected had to wait so long to be diagnosed.

Back in Rochdale, Liz Fitzsimons is determined to get her stepson home from Iraq, not least so his father, Eric, can see him while he still recognises him. She is convinced that if Fitzsimons had been treated and monitored by the army, it would never have come to this. “It’s ruined our lives,” she says. “I’m sad it happened to us, and very sad it happened to Danny, but in some respects we’re equipped to deal with it because I’m bloody determined.” She slaps the table as she speaks. “You know, they’re not getting away with it. They’re not. I’m not having it.”

• This article was amended on 29 October 2014 to remove details of Robert Kilgour’s family.