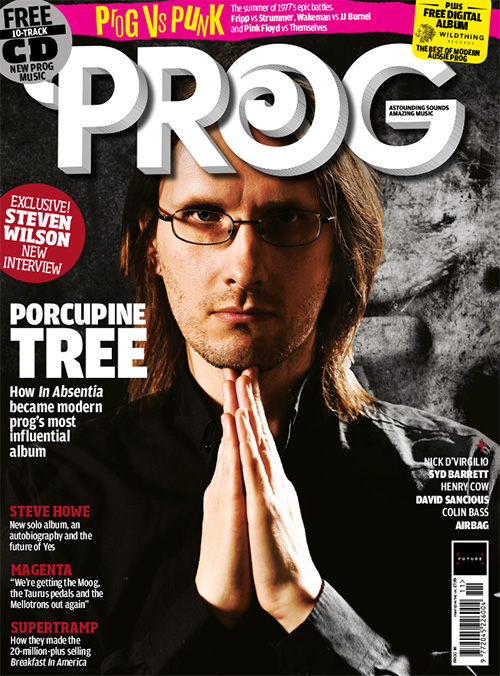

When Porcupine Tree released In Absentia in 2002, it represented not only a dramatic shift in the band’s sound – but also marked the start of a new era in modern progressive music and inspired a generation of heavy artists. Marking Kscope’s deluxe reissue in 2020, Prog took a detailed look at the album Steven Wilson described as “the beginning of the end.”

As Steven Wilson looks out over the floor of the Middle East Club in Cambridge, Massachusetts, from the stage, he can’t help feeling a little depressed. Thirty pairs of eyes stare back at him. This is the sum total of people who’ve turned up to see him and his band Porcupine Tree play the hip East Coast club.

It’s Monday, July 22, 2002, and this is supposed to be a tipping point for the group. Over the last decade, the British oddballs have existed on the fringes, becoming a rallying point for anyone with an interest in shape-shifting, vaguely psychedelic sounds without ever quite extending beyond cultdom.

But recently, things have changed. In a fairly astonishing turn of events, Porcupine Tree have been signed by Lava Records, a subsidiary of music industry powerhouse Atlantic. They have suddenly found themselves on the same label as rap-metal superstar Kid Rock and platinum-dusted MOR-grungers Matchbox Twenty.

The dream Porcupine Tree have been sold is that their new album, In Absentia, will push them to the next level. If it succeeds, Wilson and his bandmates will be sipping cocktails around guitar-shaped swimming pools in newly purchased Beverley Hills homes. But all that looks to be a long way away on this Monday night.

“You suddenly realise you’re facing an uphill battle trying to convince a lot of people who don’t know you to start caring about you,” says Wilson today. “That’s not just the fans – it’s partly the industry too.”

In Absentia would be released two months later, the first of two albums made during their dalliance with the majors. In music industry terms it was a flop, even though it outsold all their previous releases by a wide margin. Yet at the same time it reshaped the band entirely, opening them up to a new audience, and by extension ushering in a brand new era for progressive music.

Over 20 years on, In Absentia stands as a landmark. It was the first great progressive rock album of the 21st century, one whose marriage of musicianship, melody and heaviness shaped so much that followed. But it would also set its creators on a path that would see their leader dissolving them less than a decade later.

Eighteen months before he began working with the band, Gavin Harrison saw Porcupine Tree at Shepherd’s Bush Empire in west London. He’d carved out a career as an in-demand session drummer, playing with everyone from Level 42 to Iggy Pop. In 1995 he’d appeared on a solo album by former Japan and current Porcupine Tree keyboard player Richard Barbieri; it was he who’d invited Harrison along to the Empire.

“I was impressed that they could get so many people in the room playing very uncommercial music,” says Harrison, though he was less impressed with what he saw. “After about an hour, I thought, ‘That’s it, I’ve heard enough.’ I sent Richard a message saying I wasn’t feeling well.”

Having made two albums that I thought had quite accessible material on, there was a sense of frustration

Steven Wilson

Wilson was experiencing a different set of emotions. Porcupine Tree were essentially a one-man bedroom project that had grown massively out of hand. By the mid-90s they’d turned into a proper band; by the end of the decade he’d reined in his more amorphous tendencies in favour of a concise approach that veered towards pop. The albums Stupid Dream and Lightbulb Sun, released in 1999 and 2000 respectively, were packed with hooks and choruses and conventional song structures. It was as radio-ready as the band had ever got.

“But nothing was happening,” says Wilson. “Nothing doing. We just weren’t getting played on radio.”

Those two albums hadn’t disgraced themselves. The line on the sales graph had been rising steadily, to the point where they were selling 60,000 copies of each album. But Wilson still found himself bumping against a ceiling.

“Having made two albums that I thought had quite accessible material on, there was a sense of frustration,” says Wilson. “You could argue that Porcupine Tree were always the quintessential cult band. But at this point, I’m thinking, ‘We can be more than this.’”

They could – but it would take a convergence of business and artistic forces for it to have a chance of happening. Two of those forces were named Andy. The first was Andy Leff, an American music manager who had been involved with 90s pop princelings Hanson. He’d heard Porcupine Tree and loved them. He saw them in the lineage of the great progressive acts of the 70s, the ones who could serve great musical epics on one hand while hitting the pop charts on the other.

Leff arranged a meeting with the band with the blessing of Porcupine Tree’s current manager Richard Allen, owner of their original record label Delirium. The American talked a great game: Porcupine Tree deserved a major label record deal, and he was the man to get them one. Wilson was intrigued despite himself. “We were, like, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah.’ But the more I talked to Andy, the more I started to take him seriously.”

Amazingly, Leff wasn’t bullshitting. He got an in with another guy named Andy – Andy Karp, an A&R executive at Lava Records in New York. Karp was a rare breed even in 2000: a genuine music fan with posters on his wall and a working knowledge of 1970s Genesis B-sides. His love of old-school prog was offset by the kind of business savviness that reasoned there was an audience for a band like Porcupine Tree even then.

We had the songs that could give us that crossover in the way some of the classic prog bands from the 70s crossed over

Steven Wilson

“That was the notion,” says Wilson. “That there was a gap in the market. There were a lot of people out there who love this kind of music, whatever you call it – progressive rock, art rock or whatever.”

Wilson met Karp and was won over by his passion for music, and the fact that Lava’s parent company Atlantic had deep pockets. “I got very excited about the possibilities of making a record for a major American label, with all the attendant promotion and financial input that would imply.”

He decided that signing with Lava was the right move. He was aware that the label were taking a chance on a band who were way out of step with what else was going on. “When we signed that record deal, I was 33. Richard was 43. We were no spring chickens. For a major label, it was definitely a leap of faith.”

Porcupine Tree had more going for them than just a prog-loving cheerleader at the label. Wilson had been amassing music for a new album before Lava entered the picture. “We had the songs that could give us that crossover in the way that some of the classic progressive rock bands from the 70s had managed to cross over.”

But the songs he’d been writing weren’t ersatz reruns of Roundabout or Thick As A Brick. In the two years since Lightbulb Sun, his listening tastes had shifted considerably. Porcupine Tree were still anchored somewhere between the deep waters of the esoteric and the shallows of pop, but another, altogether more unexpected noise had entered their leader’s orbit: metal.

In another life Wilson could have been a member of Iron Maiden. As a teenager, he’d discovered the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal – the early 80s movement that galvanised a flagging metal scene. But he soon grew tired of cut-off denim jackets and Saxon back patches. “I’d fallen out of love with it and gotten interested in other things,” he says.

When I was introduced Opeth and Meshuggah I went, ‘This is where the innovation is – at the brutal end of metal

Steven Wilson

Around turn of the millennium, Wilson was introduced by a journalist to the music of Opeth, a Swedish death metal band who were trying to throw off the shackles of the underground scene they’d emerged from. They sounded nothing like the heavy metal Wilson knew from 20 years earlier. A mutant strain of extreme metal had appeared, its DNA intertwined with that of everything from prog to jazz and the avant-garde. Bands such as Opeth and fellow Swedes Meshuggah were straining the boundaries of the metal scene.

“For years I‘d been bemoaning the fact that no one was experimenting in rock music any more,” says Wilson. “And of course I was just looking at it through my little telescope at this very small sub-section of the rock scene. When I was introduced to bands like Opeth and Meshuggah, I went, ‘Ah, this is where the innovation is happening – at the brutal end of metal.’”

He dived in headfirst, devouring this new noise. Ever the student of music, he picked out a thread and tugged on it. “I’m one those people that’s always looking for what I can do next that’s different,” he says. “I could immediately see how elements of that could be brought into my own writing.”

That interest was strengthened when Opeth mastermind Mikael Åkerfeldt approached Wilson to produce his band’s next album. Like Wilson, Åkerfeldt was a fan of music’s dustier corners. He was also a fan of Porcupine Tree. “I’d been introduced to them by my friend Jonas Renske [singer with Katatonia],” says Åkerfeldt. “I loved them straight away. Steve became my idol. Even then I put him on a pedestal with Ritchie Blackmore and Joni Mitchell.”

The pair connected and a firm friendship was forged, one based on musical respect and a desire to warp the rules in their respective fields. Wilson produced Opeth’s Blackwater Park in 2001 and the blossoming musical bromance opened the Englishman’s eyes even wider to the potential that lay in metal.

“In the back of my mind I did think, ‘This is going to make the band seem a bit more vital and edgy. It might blow away some of these associations with old fashioned 70s rock,’” he says. “I thought that it certainly wouldn’t do any harm in disabusing some people of those kind of notions.”

Fate was smiling. Gavin came along, did the record, and eventually sort of joined the band by stealth

Steven Wilson

Wilson had already started writing the songs that would appear on In Absentia before his reintroduction to metal. ‘Old’ Porcupine Tree are still audible in the album’s first single, Trains, and the deceptively gentle anti-record label diatribe The Sound Of Muzak. But the metallic vista that had opened up before him couldn’t help but bleed into what he was doing.

“I started detuning the guitar a tone down and writing riffs,” he says. “Strip The Soul, Blackest Eyes, The Creator Has A Mastertape – then again, I’m also writing Heartattack In A Layby and Collapse The Light Into Earth, which have barely any guitar on at all.” They pointed towards the direction things were going in.

If his love of metal defined this phase of Porcupine Tree’s career, it also reshaped Porcupine Tree themselves. The line-up that entered the 00s – Wilson, Richard Barbieri, bassist Colin Edwin and drummer Chris Maitland – had been working together since 1993. But that was about to change.

A major label deal brought with it an unexpected set of pressures, not least in the commitment that would be required. As Wilson tells it, Maitland was becoming increasingly anxious at giving up a lucrative regular job playing West End shows, and this anxiety turned into tension.

Matters reached a head in rehearsals a few weeks before the band were due to go to New York to begin recording. Things were said, resulting in Maitland grabbing Wilson and pushing him against a wall. Today, the latter won’t be drawn on the specifics of what happened. “I don’t want to talk about the particular incident, but Chris wasn’t concentrating properly and wasn’t playing as well as he should have done. I lost my temper and it resulted in a parting of the ways.”

The broken friendship was repaired the following year when Maitland appeared on the debut album by Wilson’s Blackfield project. But at the time it left Porcupine Tree in a hole. That was when Harrison heard from an old friend. “Maybe nine months after I’d seen them at Shepherd’s Bush, I get a call from Richard,” says Harrison. “He said, ‘Our drummer’s just left; would you come to New York and play on this record?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’”

We worked through it really quickly. They booked 14 days for me to do the drums. I did it in five

Gavin Harrison

Wilson, Barbieri and Harrison hastily convened to share the material that had been written. “I thought, ‘This could be quite interesting,’” says Harrison. “I’d never really played on anything so heavy.” He was in, albeit initially as a hired hand. Wilson says there was no Plan B. “Christ, no. We would have had to use a session player. Andy Karp suggested the guy [Will Calhoun] from [90s funk rock band] Living Colour.”

Like Wilson, Harrison had been exploring some of metal’s far reaches. The drummer had become fascinated with the ground-breaking rhythms of Meshuggah, and his hard-hitting but intricate drum work would partly define this new era of Porcupine Tree. “It’s one of those times when it all worked out fantastically well,” says Wilson. “It could have been a disaster, but fate was smiling. Gavin came along, did the record, and then he eventually just sort of joined the band by stealth.”

When Porcupine Tree arrived in New York in early 2002, they found a city weighed down by emotion. It was just a few months after the epochal events of 9/11, and an air of eerie dislocation still permeated the air. “It had a strange feeling to it,” says Wilson. “It was in this healing period. I don’t think it fed into the record, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there. It must have had an influence.”

One song certainly bore the psychic imprint of this huge tragedy. On the day that the planes crashed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center, Wilson was working on music in his home studio in the UK. When he surfaced for air and heard the news, he abandoned the track he had been working on. But the emotions that coursed through him manifested in another piece of music he began writing weeks later: the album’s eventual closing track, the spectral piano ballad Collapse The Light Into Earth.

“It’s a song about a break-up, but it’s definitely informed by what happened,” says Wilson. “I didn’t want to write about 9/11. It would have felt like jumping on the grief bandwagon. But at the same time I felt the sense of sorrow and of shock that everyone else felt. I found myself sitting at the piano, writing this song. It was actually influenced by Jacques Brel’s If You Go Away, but the sense of sorrow is what everyone felt in the days after 9/11.”

In New York, the band were sheltered from the psychic turmoil of the city by the $2,000-a-day [£1,500] sanctuary that was Avatar Studios. Formerly known as the Power Station – it recently reverted back to the name – the venerated space had played host to the likes of David Bowie and Madonna. If nothing else, it brought home that fact that Lava were serious about their investment. “We worked through it really quickly,” says Harrison. “They booked 14 days for me to do the drums. I did it in five. It was efficient.”

We didn’t fit… eccentric Englishman playing this odd music, people didn’t know where to put it

Steven Wilson

Efficient but expensive. The overall cost of making the album ran into six figures: a fortune now, but smallish change in an era where the music industry had yet to be kneecapped by illegal downloading. By the end of the campaign, Lava had lavished around $400,000 [£300,000] on Porcupine Tree. “If you include tour support, then yes,” concedes Wilson.

That spend wasn’t apparent when Porcupine Tree turned up at The Middle East club to kick off the In Absentia campaign. The album was months away from being released – but, still, only 30 people? Harrison, for one, was wondering what he’d let himself in for. “I’d just been with Claudio Baglioni, Italy’s answer to Elton John,” says the drummer. “We were filling the Olympic Stadium – 80,000 people – I’ve got my own limo, my own five-star hotel room and business class flights. I’d gone from that to a clapped-out tour bus and very few people in tiny rooms.”

Wilson insists the opening show wasn’t indicative of that US leg of the tour. “I don’t want to give the impression that every night was like that,” he says. “We’d go out and sell out the House Of Blues in LA and the Nokia Theatre in New York. If it had all been bad, it would have been extremely soul-destroying and the band would have probably broken up. But we saw enough to make us optimistic for the future.”

“It was miserable,” counters Harrison. “Extremely miserable.”

Slumming it around New England wasn’t the worst of Porcupine Tree’s experiences. That honour went to their stint with Yes on the prog giants’ tour in support of 2001’s Magnification. Despite his distaste at being pigeonholed, Wilson figured there was a generational overlap between the two bands, audience-wise.

It was a rare moment of naiveté on his part. Porcupine Tree were initially allocated a 45-minute slot, kicking off at 7.30pm. As the tour progressed their stage time got shorter and earlier, until they found themselves onstage, literally waiting for the arena doors to open so they could start playing. Wilson sighs at the memory. “I could not wait to get off that tour,” he says.

In Absentia was released on September 24, 2002. Its cover featured a striking, eyeless self-portrait taken by Danish artist and designer Lasse Hoile. It perfectly reflected the album’s themes of absence and madness – though it was utterly out of keeping with prevailing trends.

Sales started slowly and pretty much continued that way, at least in terms of a band signed to a major label. According to Wikipedia, the album stormed the German charts at No.58. In France it reached No.143. There’s no record of it registering in the UK or US at all.

Lava shoulders some of the blame in Wilson’s eyes. He points to the fact that the label sent out three different songs as singles at the same time to appease different radio formats, dispersing focus. But he also concedes that Porcupine Tree were fundamentally a hard sell. “I don’t want to be the clichéd guy that says, ‘I did everything right; the record company fucked it all up,’” he says. “It wasn’t entirely down to them. We didn’t fit. Kid Rock was an easy sell. Matchbox Twenty was an easy sell. This bunch of eccentric Englishman playing this odd music, people didn’t know where to put it.”

It opened up a whole new audience for them, and it helped open up a whole new audience for progressive rock

Mikael Åkerfeldt

It’s impossible to argue with that. But there’s another reason why In Absentia was so pivotal. The band may have flown over the heads of fans of mainstream music and the disinterested masses who turned up to see Yes, but the album cracked open the door to another constituency entirely. Its heavier tracks were picked up by metal radio stations in the US. Combined with the sideways patronage of Åkerfeldt and Opeth, Porcupine Tree found the make-up of their audiences changing.

The small but devoted army of fans who’d followed them through the various protean phases of their career – psychedelia, progressive rock, something vaguely approximating pop – was suddenly swollen by a legion of metalheads pulled in by the jagged edges of Blackest Eyes and Strip The Soul.

“I discovered Porcupine Tree around 2006,” says Jan Hoffmann of German post-rockers Long Distance Calling. “Particularly with In Absentia, I had never heard anything like it. It was a huge influence on us and the bands we knew.”

There’s an irony to all this that Wilson brings up himself: if Porcupine Tree had stuck with the breezier, poppier sound of Lightbulb Sun and Stupid Dream, they might have had more chance of breaking the ceiling for prog-leaning bands in the early 00s.

But the comparatively lowly commercial success of In Absentia is in inverse proportion to its artistic impact. It didn’t just change the band – it changed the course of progressive rock from that point onwards. They weren’t the first band to combine forward-looking musicianship with the visceral energy of metal; a line could be drawn from Rush to Porcupine Tree’s most notable precursors Dream Theater, taking in the likes of Queensrÿche, Watchtower and Voivod. But no one had so consciously thrown themselves into it like Wilson.

“It clicked with a lot of people they’d never clicked with before,” says Åkerfeldt. “It opened up a whole new audience for them, and it helped open up a whole new audience for progressive rock. You suddenly heard a lot of bands who sounded like them.”

Typically, Wilson has rather mixed feelings about the compliment. “The first thing is that it’s very flattering to my ego,” he begins. “I do hear the influence on a lot of other bands, and I do think the record sounds quite contemporary and quite current. In retrospect, I can see that we were doing something different and innovative.

“But the second thing – which is more negative – is that people think that’s the kind of music I want to hear. Anyone who comes up to me and says, ‘Please listen to my album, it’s very influenced by what you did with In Absentia or [follow-up] Deadwing’, I say, ‘Well, don’t give it to me then, I’m not interested.’ The last thing I want to hear is music that sounds like Porcupine Tree 18 years ago.” He laughs self-deprecatingly. “The arrogance of it! But I don’t.”

What isn’t possible is that Porcupine Tree or any band would ever become my primary creative outlet ever again

Steven Wilson

It’s this wilfulness that would prompt him to split Porcupine Tree and embark on a solo career just under a decade later. Having embraced metal with In Absentia, he found himself increasingly trapped by the genus of music he’d been partly responsible for. “Very quickly I discovered that it came with its own set of limitations. I still feel in a sense that the band broke up when it did is because I felt like we had painted ourselves into a corner as this prog metal group. And I was very tired of that. I wanted to do other things. So in a sense In Absentia was also the beginning of the end.”

He’s fielded regular requests to reform Porcupine Tree down the years from fans and the music industry alike. His response has always been a straight ‘no.’ That’s something that is unlikely to ever change. “A one-off show, that is possible,” says Wilson. “But what isn’t possible is that Porcupine Tree or any band would ever become my primary creative outlet ever again. I don’t think I’m made for being in a democratic collective environment.”

That may be the case now, but it certainly wasn’t then. As fine as the solo work he’s subsequently put out, nothing has had the influence that Porcupine Tree had. And no album of his has been as influential as In Absentia.