When it comes to the story of the Beatles, no one has been more vilified than Yoko Ono. For nigh on 50 years, she has been cast as the villainess who broke up the group, the evil temptress who cast a spell on John Lennon, married him and proceeded to tear the time-eclipsing rock band asunder. At least, that’s how the mythology goes. It has made for a story — one part racist, two parts misogynistic — that seemingly never dies, that has persisted into the present day.

In September 1980, during the final weeks of his life, Lennon admitted his frustration to journalist David Sheff. “Anybody who claims to have some interest in me as an individual artist, or even as part of the Beatles,” he remarked, “has absolutely misunderstood everything I ever said if they can’t see why I’m with Yoko. And if they can’t see that, they don’t see anything.” Incredibly, not even Ono’s unfathomable trauma at having witnessed her husband’s senseless murder would quell the naysayers and detractors who disparage her name.

In February 1988, with the first decade of her widowhood nearing its close, Ono would quietly and, perhaps most important, swiftly perform an act of kindness that preserved what music historians have described as the Holy Grail of the Beatles’ legacy. For Ono, the opportunity would arrive in the unlikely form of Leena Kutti, a 43-year-old Estonian immigrant whom Ono would never meet.

Like Ono, Kutti was a headstrong expatriate who was willing to make considerable sacrifices to further her art. The kanji meaning of “Yoko” translates as “Ocean Child,” befitting the woman who would travel across the breadth of two oceans as she made her way in the world as a budding conceptual artist — first, in 1940, when her family first left Tokyo for New York City, and later, in 1966, when she opened her "Unfinished Paintings" exhibition at London’s Indica Gallery. "Unfinished Paintings" would shortly bring Lennon into the artist’s orbit, and one of the 20th century’s greatest love stories would be born.

Kutti’s immigrant journey had begun some two decades earlier. In 1949, five-year-old Kutti disembarked at Ellis Island from the USS General Harry Taylor, the Navy transport ship that ferried her, along with her mother, her sister, and thousands of other refugees from the West German port city of Bremerhaven, where they had alighted after escaping the horrors of Soviet-occupied Estonia. The Kuttis were among the fortunate few who were able to flee the reassignment camps. Hundreds of thousands of others would be doomed to lives of toil and despair in the far reaches of Siberia.

For Leena, the voyage on the USS General Harry Taylor had been a revelation. She would never forget the first time she was presented with a fresh orange during her two-week crossing. Or when she and her family were processed at Ellis Island and the attendant gleefully noted that Leena had been born on Halloween, a foreign concept to the refugee if ever there were one. Over the ensuing years, her family life would take the predictable course for members of the Eastern European immigrant class. Until the mid-1950s, the Kuttis lived under the good auspices of a sponsor family in suburban Baltimore. Meanwhile, Leena’s mother struggled to make ends meet in her adopted country while proudly working towards American citizenship for herself and her school-aged daughters. And later still, in February 1964, as Kutti pursued an undergraduate art degree at the Maryland Institute, she would experience a bona fide pop-cultural explosion. Along with 75 million other Americans, she tuned in to watch the Beatles perform on "The Ed Sullivan Show," and she was hooked.

By the 1980s, Kutti was living the life of a working New York City artist, plying her passion by night as a painter, while making ends meet by day as a temp. The city afforded her with an endless array of short-term assignments — clerical jobs, mostly — that left her with plenty of hours to make new art. In those days, she was living in Brooklyn — “when it was deserted,” she later recalled, “before it became Hipster Land.” By then, she had tried on many careers, including a stint in documentary filmmaking, and enjoyed a bevy of adventures — even hitchhiking cross-country with a girlfriend to California during the 1970s. And her tastes had grown edgier over time, leading her to favor the bluesy hues of the Rolling Stones over the Beatles’ sweet optimism.

Love the Beatles? Listen to Ken's podcast "Everything Fab Four."

In February 1988, Kutti accepted an assignment to work at G.P. Putnam’s Sons, the vaunted New York City publishing house. The temp agency assured the 43-year-old artist that it would be a short-lived gig — a week at the most. Kutti was in the running for a long-term opportunity that would soon be opening up at Credit Suisse. The job at Putnam’s brought her to the New York Life Building — and, more specifically, to the basement. Known as the “storage room” in the parlance of the publisher’s staff, the dusty basement level was packed to the gills with every possible kind of detritus. It was mostly clerical stuff — paperwork and contracts associated with a century in the life of American publishing. But there were strange things, too, hidden among the attendant accumulation — objets d’art such as paintings, sculpture, photographs. And Kutti’s job, more or less, was to throw it all out.

In 1982, Putnam’s had purchased Grosset and Dunlap, the august imprint that could trace its lineage back to 1898. The publisher was founded by Alexander Grosset, a shy Scotsman who teamed up with George Dunlap, a gregarious Pennsylvania transplant, to raise $1,000 in order to establish a hardcover reprint house that would make a fortune peddling the likes of Rudyard Kipling and Zane Grey before taking aim at the burgeoning children’s literature marketplace. “'It’s like finding a cornucopia,” Peter Israel, Putnam’s president, said at the time of the 1982 acquisition. “They have a backlist of children’s books second to none” — classic works like Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, Tom Swift and the Bobbsey Twins. But what Putnam’s was really after was lucrative Ace Books, Grosset and Dunlap’s mass-market paperback division. By 1988, Putnam’s offices in the New York Life Building were overflowing, literally, with material.

Assigned to help clean out the storage room, Kutti rolled up her sleeves and began sifting through the materials, which had accumulated in haphazard fashion over the decades. The foreman, also a temp, told her that their task, essentially, was to empty the basement out. He expected that they would be consigning most of the stuff to the garbage heap, but on the off-chance that they found anything of value, those items could be transported to the company’s storage facility across the river in New Jersey.

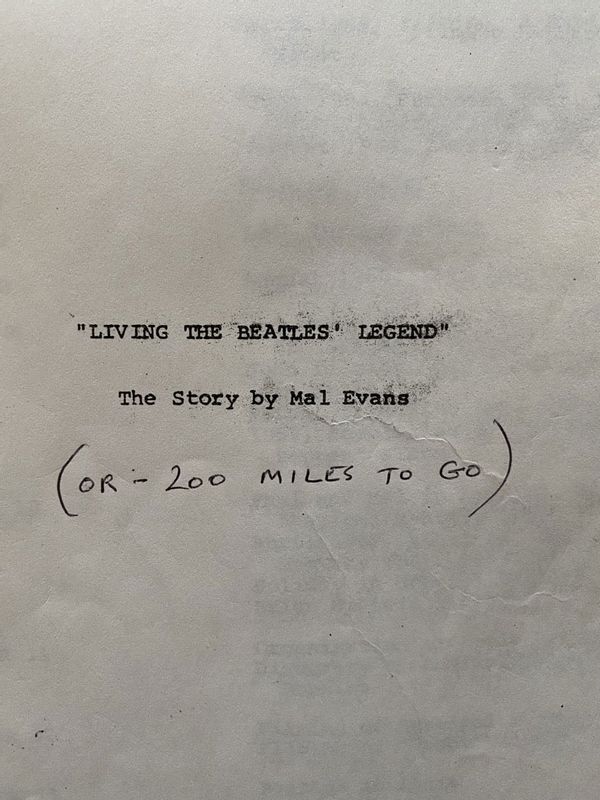

It was around the second day on the job when Kutti happened upon the four bankers boxes. Almost immediately, she could tell that they held contents of a particular significance. As she sifted through the boxes, she gazed at what seemed like vintage photographs of the Beatles — thousands of them. And then she found a manuscript titled "Living the Beatles’ Legend: Or 200 Miles to Go." It was an oddly formatted specimen — printed in all caps. And further still, she discovered a spate of leather-bound diaries. Leafing through their pages, Kutti was able to ascertain that the boxes must be the property of Malcolm Evans, a name that meant nothing to her. From the looks of the booty that lay before her in the basement, he must have been some kind of chronic hoarder, an avid photographer apparently, and an enthusiastic journaler who peppered his voluminous diary entries with madcap, colorful — even psychedelic — illustrations.

Evans’ loss had been felt acutely in the Beatles’ inner circle. “Mal was the nicest, gentlest person,” George Harrison lamented. “He was a big guy, but he was really sweet.” Paul McCartney was even more vociferous in his defense of his fallen comrade. “Mal was a big loveable bear of a roadie,” he recalled. “He would go over the top occasionally, but we all knew him and never had any problems. The LAPD weren’t so fortunate. They were just told that he was upstairs with a shotgun and so they ran up, kicked the door in, and shot him.” McCartney was particularly emphatic when it came to Mal’s state of mind during the tragic events of January 1976. “He was not a nutter,” he said.

For Kutti, the discovery of Big Mal’s untimely demise made for a bitter pill, a fact that seemed to grow even more tragic when she learned that he had left behind a wife and two children in England. Flush with a new sense of resolve, she was determined to get those prized bankers boxes into the hands of Evans’ family. In her zeal, Kutti brought the materials to the attention of the foreman, who reminded her that they were on a search-and-destroy mission, not a recovery project. But Kutti persisted, informing him “that there’s stuff here about the Beatles.” Incredibly, the foreman thought she was referring to insects, which left her even more frustrated. “I guess he just wasn’t into music,” she said. “I could tell that he was older than I was.” But she wasn’t giving up the ghost so easily. When she insisted that the boxes were the rightful property of Evans’ family, the foreman threw his hands up and sent Kutti to the Putnam’s corporate offices, where she spoke with Louise Bates.

After acquiring Grosset and Dunlap, Putnam’s moved the entire operation — save for the basement storage room, that is — to their corporate facilities, which were located 10 blocks north of the New York Life Building at 200 Madison Avenue. At this point in her career, Bates had taken on a kind of legendary status in the publishing industry. In her role as Director of the Contracts, Copyrights, and Permissions department, Alyss Dorese didn’t flinch when it came to finding a place for Bates at Grosset and Dunlap. “She was well over 65 when I hired her,” Dorese recalled, “and I got a lot of flak for hiring someone of her age. But she was a terrific person and a wonderful worker of the old school who loved detail.” Putnam’s had kept Bates on after purchasing Grosset and Dunlap, and Bates had come to adore her well-earned senior status as one of the industry’s doyens. When she met with Bates in her Midtown office, Kutti could tell that she was being taken seriously. But it also became clear that Mal’s bankers boxes made the older woman feel uncomfortable. Soon, Bates was explaining that she would need to check with legal, possibly even send the materials out to Los Angeles for consultation with the original lawyers who handled the contract.

To Kutti’s way of thinking, Bates appeared to be overly concerned. On its face, the evolving imbroglio seemed like a decidedly simple issue to the temp, with an equally simple solution: by rights, the materials belonged to the surviving family members back in England. That Saturday, February 13th, Kutti decided to take matters into her own hands. She took the subway uptown to the corner of W. 72nd Street and Central Park West. Stepping up to the copper-plated sentry box adjacent to the Dakota’s majestic archway, Kutti handed the doorman a sealed envelope addressed to “Ms. Yoko Ono,” with the word “personal” scrawled underneath. Having written her telephone number in the note, Kutti didn’t mince words. “This is regarding some of Malcolm Evans’s personal effects,” she wrote. “I feel they should be returned directly to the family.” Kutti knew that leaving a note for John Lennon’s widow, a lightning-rod of a public figure who surely received countless inquiries every day, was a long shot at best.

But Kutti didn’t stop there. She was determined to make a thorough accounting of Mal’s forgotten archives. That Monday, she compiled a six-page inventory of the bankers boxes. As she began to organize the materials, they seemed even more tantalizing than before: there was an autographed color photo of Elvis Presley, a signed drawing of Mal by John Lennon, and yet another drawing of the roadie by McCartney, inscribed with the words “To Mal the Van from James Paul the Bass.” There were 10 Super 8 films in total, with titles like “Family Holiday,” “Beatles India,” “Africa,” “Greece” and “Plane Trip (Paul).”

When Kutti returned to the storage room later that week, with her gig at Putnam’s swiftly coming to an end, the boxes were no longer in the basement. Not to be deterred, the temp made her way to Bates’ Midtown office, where all of the boxes were stacked neatly beside her desk. Again, Kutti couldn’t help noticing how uncomfortable and worried the woman seemed — “like she wanted to deal with the stuff and get it over with as quickly as she could.” Bates seemed to be fretting in particular about “the lawyers in LA,” who wanted the materials, but didn’t want to pay the freight to ship the boxes to the West Coast. For the life of her, Kutti couldn’t make sense of the fact that “they were so worried about the cost, that they couldn’t begin to understand how important and valuable all of this stuff was.”

With her new gig beginning on Monday at Credit Suisse, Kutti realized that the clock had seemingly run out. But she had one more card up her sleeve. She made a Xerox copy of the inventory, rifled through the international telephone books at the New York Public Library, and, putting pen to paper, wrote a letter to Lily Evans at 135 Staines Road East in Sunbury-on-Thames. If nothing else, the temp wanted to ensure that Mal’s widow knew about the bizarre drama playing out in New York City.

What Kutti didn’t know is that Yoko had received her message alright. Indeed, by the time Kutti had begun her new assignment in Credit Suisse’s 11 Madison Avenue offices, the wheels were already in motion at Gold, Farrell, and Marks, Apple Corps’ law firm, which was coincidentally just across the street from the New York Life Building. One of the firm’s partners, Paul V. LiCalsi, had taken the lead on behalf of Yoko and Neil Aspinall, Mal’s former counterpart in the band’s circle who had been appointed in 1976 as Executive Director of Apple, the Beatles’ holding company, in the wake of the dissolution of the group’s partnership.

What LiCalsi and his team accomplished in a few short days was a masterpiece of lawyering. When Apple took possession of the bankers boxes, they extracted an agreement from Putnam’s to protect Mal’s legacy. Putnam’s attorney Matthew Martin wrote to Apple, stating that “per our phone conversation of March 14, 1988, this will confirm that neither Grosset and Dunlap nor the Putnam Publishing Group or any of its subsidiaries or affiliates own any copyright or publication rights in and to the untitled literary work on the Beatles (including text, photographs, drawings, memorabilia, and other materials prepared and collected for the work) which was to have been authored by Mal Evans.” Most importantly, Martin added, parroting Apple’s express instructions, “please be assured that neither Grosset nor Putnam has any plans or intentions of publishing any material authored or prepared by Mal Evans.”

Within a year, Yoko made a point of meeting with Lily and her adult children Gary and Julie in London, where they shared a meal and talked about old times. In the late 1960s, their paths had crossed often. Gary held cherished memories of John and Yoko playing Father and Mother Christmas at Apple’s annual holiday bash. Lily and her children were grateful, of course, for Yoko’s heroic role in making good on Kutti’s discovery and swiftly returning Mal’s effects to his family after languishing for so many years in cold storage. In Gary’s memory, it was a beautiful evening, although he had been nervous at the outset. Now in his late-20s, Gary had been self-conscious about his weight at the time, and Yoko quickly intuited the source of his anxiety. “Just be yourself,” she told him. “Stop trying to look slim for me.”

For Gary, the reunion made all the difference. “That completely broke the ice,” he recalled. As the hour grew late, Yoko made the sad realization that their loved ones, in one way or another, had been vanquished by gun violence. They shared a tearful embrace before they left her suite that night. For Gary, Yoko’s warmth and generosity had helped him to rethink his dad’s role —not only with the Beatles and their lives, but also his own.

For several more years, the materials would be stored in the family’s attic, where Gary would periodically make forays into Mal archives and come to know his father beyond the grave. And as Gary came to discover, there would be hard truths to be learned about the reality of his father’s existence. Mal Evans was a man who lived his life in compartments, one of them reserved for his family and the other for the Beatles. In the former, he reveled in the love of his wife and children, whom he unquestionably adored. In the latter world, he lived like a medieval rogue, a free-wheeling sort who sucked the marrow out of every last moment. Mal ultimately lived the way he did — with great deliberateness, often recklessly, and without apology — because he expressly chose to do so, step by step.

For Mal, being in close proximity to the Beatles’ special brand of stardom, and having ready access to every form of pleasure known to humankind, trumped the joys and commitments of family. And with nary an exception, when it came to the Beatles versus his family, the Beatles won the sweepstakes every time, bar none. Even in his final days, when he was living thousands of miles and an ocean away from his estranged family with another woman in Los Angeles, Mal still couldn’t quite make it home.

Over the years, as the archives rested in the garret at 135 Staines Road East, their mere existence has emerged as the stuff of myth among Beatles aficionados the world over — a Holy Grail, of sorts, filled with never-before-seen photos and untold treasures and artefacts. At Beatles conventions, fans speak in hushed tones about Mal’s lost diaries and his unpublished memoirs. In 2004, the archives briefly made headlines across the globe when Fraser Claughton, a 41-year-old farmer from Tinkerton, England, claimed to have discovered Mal’s long-lost treasure trove in an old suitcase. Having travelled to Australia for a friend’s birthday celebration, Claughton ventured into a flea market outside of Melbourne, discovered the priceless items, and quickly snapped up the timeworn luggage for the bargain sum of 50 AUD. The ensuing jubilation over the supposed recovery of Mal’s archives proved to be short-lived, when Claughton’s discovery was revealed to be a hoax, a cynical money-grab that was swiftly rebuked by collectors. Unbeknownst to the public, the materials were safely ensconced in Sunbury-on-Thames. The following year, Lily put an end to the speculation when she consented to a feature story in The Sunday Times Magazine, which published a few excerpts from Mal’s diaries for the first time.

In the years since Ono and Kutti’s steadfast efforts on behalf of his family, Gary’s appreciation for the archives has only deepened. What were once painful reminders of a wayward, seemingly indifferent father have come to provide a powerful reconnection with the past. Gary has even found a sense of solace amidst his dad’s carefree, world-breaking adventures with the Beatles. Somewhere beyond the roadie’s own flaws and infelicities, the pages of Mal’s diaries, painstakingly recorded from 1962 to the mid-1970s, reveal an abiding affection for his son. For Gary, the archives’ mere existence has made all of the difference.

The same woman who saw “Now and Then” into the hands of the surviving Beatles in the 1990s — and into the ears of the whole wide world in 2023 — didn’t blink an eye when it came to preserving a family’s legacy. Bravo, Ocean Child.

"LIVING THE BEATLES LEGEND: The Untold Story of Mal Evans" will be released Nov. 14.