Each year on Jan. 27, the anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp complex in Poland, an International Day of Commemoration memorializes the victims of the Holocaust. This somber day focuses on the destruction the Nazis and their collaborators inflicted on Jewish communities throughout Europe. But there is another way to honor those 6 million murdered: remembering the ways they lived, not only the ways they died.

I am a sociologist who focuses on Holocaust memory and education. My interest is both professional and personal – my grandparents were Holocaust survivors. During research into my own family history, I became absorbed by the largest body of writing collectively created by survivors in the postwar years: “yizker bikher,” which is Yiddish for “memorial books.”

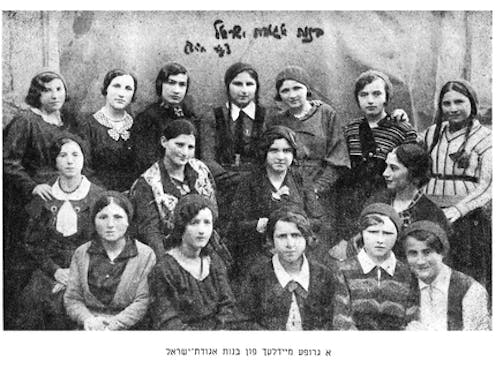

There are over 1,000 of these volumes recording the lives and deaths of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. Yizker bikher were collaboratively written after World War II by survivors, many of whom sought to reclaim their lives and memories by contributing to the books, and published by mutual aid societies called “landsmanschaften” in Yiddish. Defying the Third Reich’s attempt to wipe Jewish culture off the map, these books memorialize writers’ hometowns, commemorate murdered loved ones and pass on collective memory to their victims’ descendants and their own.

‘Like life itself’

Instead of dry, matter-of-fact historical material, yizker bikher give rich descriptions of everyday life before the war: folklore, idioms, superstitions and life stories. Only toward the very end of any given volume do they turn to experiences during the Nazi era. Woven together with the text is all kinds of visual material: hand-drawn maps, sketches, photographs and documents from daily life, including meeting notes, newspaper clippings and notices of events in the “shtetl” – Yiddish for a small town. Yizker bikher might be compared with a communal scrapbook, capturing both personal lives and the community’s.

Despite writers’ desire to focus on life, the volumes are framed by a profound sense of loss. One Polish contributor simply states: “There was a Jewish community in Czyzew, and it is no longer.” This line distilled the very essence of yizker bikher: Something was there, and now it is not.

Yet the authors brought entire communities back to life, describing both people and places with words like creative, vibrant, lively, dynamic, exciting, sublime, energetic, outstanding, vivacious, rich, effervescent and wondrous. One small shtetl in Poland was “a lively town with virtues and flaws, greatness and smallness, storm and tranquility, light and shadow like life itself.” Another is described as a “warm nest for Jewish life and culture” – an idea yizker bikher consistently emphasize, as well as the diversity of Jewish beliefs.

Authors highlight individual members of their communities, bringing the everyday to life. Writers often say that their shtetls were made up of Jews who were “simple” and “common,” such as “Chaikel the wagon driver and Yakir the shoemaker” from Sochaczew, Poland. Yizker bikher paint a picture of the shtetls as both “ordinary” and diverse. In Chorzel, Poland, for example, there were “rabbis, scholars, honorable community activists, wealthy and poor people, observant people and free-thinkers, zealots and heretics, maskilim [Jews who encouraged adopting more secular European culture] and ignoramuses, philanthropists and misers, merchants and tradesman, people interested in improving the world and Zionist pioneers.”

“Maybe our town Działoszyce was not very different from hundreds and thousands of other Jewish communities in eastern Europe,” one Polish writer muses. “Staszów was one of the countless small Jewish towns of Poland, one of the shtetls,” another writes. While the authors spend hundreds of pages explaining what made their homes so very special, they still situated themselves within a much broader Jewish community; they saw their lives and fates as intertwined.

Tribute and protest

As a whole, yizker bikher represent an extraordinary effort against oblivion. Their authors sought to create an everlasting memory, to avoid the complete erasure that seemed a possibility after the horrors of the war. Each volume is a form of protest that stresses the urgency of survival, continuity and history. Each one is a lament – but also a concerted effort to reclaim humanity and accountability.

Sometimes the accounts border on the rosy and nostalgic, but, time and again, the message is clear: death should be remembered, but life should be celebrated.

Jennifer Rich does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.