The voters of Fayette County have spoken, and they’ve said that they don’t need a hospital in this rural community of 25,000 people, one hour southeast of Austin — or at least not enough to pay for it. In a landslide vote Thursday night, county residents overwhelmingly rejected a proposition to create a taxing district for St. Mark’s Medical Center in La Grange, which would have kept the deeply indebted hospital open for the foreseeable future. As the polls closed, it was clear that the idea of propping up the institution with public money didn’t have a snowball’s chance in Central Texas. The final tally was 1,360 for, 5,600 against.

“I’m very proud of the grassroots effort that stood against the taxes,” Deborah Frank, the chair of Fayette County’s Republican Party and a member of Concerned Taxpayers of Fayette County PAC, told the Observer Friday. Her group swiftly mobilized an opposition campaign against the proposition after it was put on the ballot in April, holding public meetings and distributing yard signs reading “NO NEW TAXES.” Their message: People here are already taxed enough and shouldn’t be forced to bail out a private institution simply because it’s made what they see as bad financial decisions.

Voters apparently took the message to heart.

The resounding loss is expected to push the 65-bed hospital, which is at least $14 million in debt, even closer to financial collapse. And it comes at a time when the headwinds against rural hospitals in Texas are especially strong.

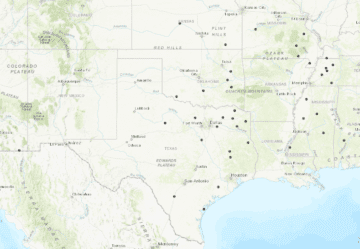

Across the state, roughly 20 rural hospitals have shuttered since 2013 — casualties of low patient volumes, stingy Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates, and the burden of operating in Texas, which has more uninsured people than any other state. Seventy-five more are at risk of closing down.

Other hospitals near Fayette County in Central Texas have struggled to stay afloat or have gone under completely in recent years. Hospitals in Rockdale and Cameron closed in December; Bellville’s was on life support this spring until a last-minute deal was made to save it. The hospital in Weimar has closed twice since 2012.

Rural hospitals have increasingly turned to taxpayers as a way to make ends meet, with mixed results. After the hospital in Crockett closed in 2017, voters twice refused to OK a tax increase that would have funded it. Bosque County voters opted not to fund their hospital with public money in 2010, though they finally decided to do so last year. Montague County residents allowed Bowie Memorial Hospital to close in 2015 after anti-tax opponents ran a grassroots campaign to characterize the plan as a boondoggle. The hospital eventually reopened, but under the operation of a company that does not accept commercial insurance and charges exorbitant fees.

The Concerned Taxpayers of Fayette County took a page out of Bowie’s book, calling six public meetings in six weeks. Combined, the meetings were attended by approximately 1,000 people, some of whom peppered hospital officials with questions about the proposed tax of 10 cents per $100 home valuation, Frank said. When St. Mark’s reps failed to show at the last three meetings, another member of the group prodded them by posting a picture of their empty chairs on Facebook. The PAC demanded detailed financial records from the hospital and lambasted officials for not providing them. (A St. Mark’s board member told the Observer that at least one of the documents was not released because it contained “proprietary” information.)

“I feel like there’s so much fraud out there in Medicaid, insurance companies, the government in general,” Frank said. “In my opinion, more taxes is never the answer until you fix the problem. We feel like St. Mark’s isn’t trying to fix the problem.”

At St. Mark’s, the signs of financial stress had been showing for years. Michael Corker, the hospital board’s vice chair, said that the facility in recent years pared its staff down from 70 to 55. Three years ago, it opted to stop delivering babies, which shaved off another $500,000 or so in annual expenses. The hospital tried to join larger systems such as Baylor Scott & White and Seton to slow the bleeding, but prospective partnerships never came to fruition.

Now St. Mark’s finds itself in crippling debt, with little hope of digging out sans tax revenue. The tax levy would have generated about $3 million in extra funding for the hospital each year.

If St. Mark’s closes, patients will have to travel 20 miles to Smithville or 26 miles the other direction to Columbus to find an emergency room. That extra travel time could mean the difference between life and death in emergency situations, Corker said. That appears to be at least partially borne out by a 2017 federal study indicating rural Americans are at higher risk of dying from unintentional injuries, stroke and other causes — a problem exacerbated by long travel times between trauma centers.

Frank said those concerns have been overblown by the Save St. Mark’s PAC, a pro-hospital tax group, in its campaign. “We’re surrounded by medical facilities,” she said, referring to hospitals in Smithville, Columbus, Bastrop and College Station. But Corker noted that neither the Smithville or Columbus hospitals have a full-time surgeon on duty. In fact, at the moment, when the surgeon isn’t at the Columbus hospital, patients needing emergency surgical care are sent to La Grange instead.

With the failed vote, St. Mark’s won’t shut down overnight, Corker said. And while the board will continue to explore other options, the hospital’s future looks bleak.

“There’s no telling how long we can stay open,” he said. “We’ll see what tomorrow holds.”