Nature loss directly threatens half the global economy. The rapid destruction of biodiversity should alarm the many Australian businesses dependent on nature, such as those in agriculture, tourism, construction and food manufacturing. Yet nature considerations are often ignored in business decision-making.

At the Global Nature Positive Summit in Sydney this week, scientists, politicians, conservationists and business leaders have gathered to discuss ways to help nature in Australia – not just by protecting it from damage, but improving it. Getting more businesses interested in – and taking positive action on – nature conservation is key to the talks.

Reducing the environmental impact of a business first requires measuring that impact. It might seem an impossibly difficult task. Nature is a diverse and intricate web of connections. How can we capture that in a number?

Nature is indeed complex – but measuring how a business intersects with it need not be.

Uncovering impacts on nature

The fishing industry depends directly on stocks of wild fish. And a housing developer has a direct impact on nature if they clear natural vegetation to build a new suburb.

Businesses interactions with nature can be indirect, too – for example, a margarine producer who uses canola oil from a grower who depends on bees for pollination. Builders might indirectly harm rainforests in Indonesia by buying timber grown there. A superannuation company investing in that developer is also having an indirect negative impact.

From next year, Australian companies will be required to measure and report their climate impacts. While businesses are not yet required to disclose their impacts on nature more broadly, many are moving in that direction – both in Australia and globally.

For example in 2022, more than 400 of the world’s largest corporations called for mandatory disclosure of nature impacts. They included Nestlé, Rio Tinto, L'Oréal, Sony and Volvo. And many early-adopter businesses have begun voluntary disclosures.

Guidelines are available to help businesses understand and measure their impacts, however progress is slow. This is partly due to a perception from business that the task is too complex.

Nature assessment is challenging. Unlike identifying a company’s contributions to climate change – by measuring tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions – there is no agreed single measure of impacts on nature.

What’s more, different people ascribe different values to aspects of nature. Rightly or wrongly, for instance, most people would probably value a koala over a mosquito.

Drawing on the expertise of ecologists

Despite the difficulties, gauging the extent to which a business affects the environment can be done. Essentially, it involves three steps:

understanding how a business broadly intersects with nature

evaluating how specific business activities intersect with and put pressure on nature

measuring and reporting the degree to which specific activities are impacting on the condition of nature. In other words, is the state of animals, plants and ecosystems improving or worsening?

Online tools such as ENCORE can get businesses started on the first step – understanding a business’ broad impacts and dependency on nature.

Many businesses are moving to the second stage - evaluating the specific business activities that put pressure on the environment, and determining the extent to which businesses depend on particular services ecosystems provide.

The pressure a business places on nature can be measured via specific metrics, such as the amount of water consumed, air pollutants emitted, waste generated or area of land changed. Again, a suite of online tools and metrics can help with this.

The next step is more complicated, yet essential. It requires businesses directly measuring their impacts on specific animals, plants and ecosystems. For this, we can turn to the expertise of ecologists.

Individuals of a species can be hard to count, and extinction risk can be hard to measure. So ecologists often describe and monitor a species’ habitat – the environments in which a species can survive and reproduce – as a proxy for the fate of the species itself.

Ecosystems – such as a rainforest, wetland or desert – can be described as being in good or poor condition. The rating depends on whether all the ecosystem’s plants, animals and other components are present, or whether unwanted components, such as weeds or invasive species, are found there.

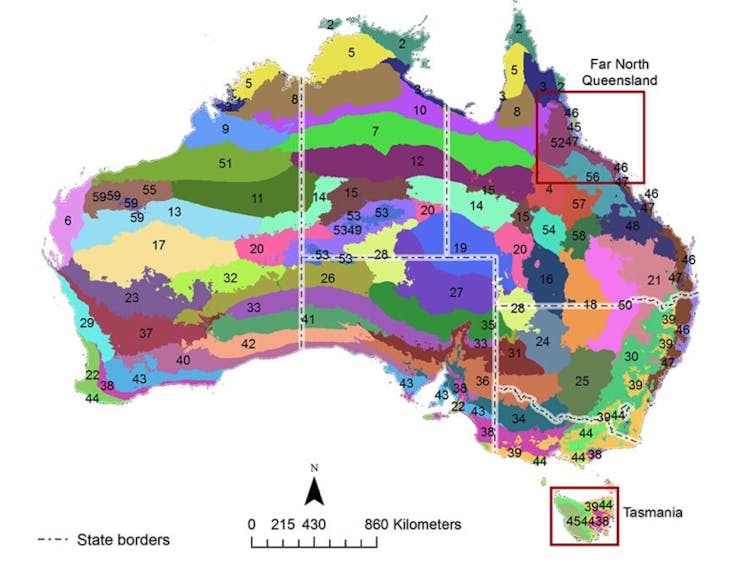

In addition, maps, showing ecosystem condition and extent are available for much of Australia.

Habitat mapping is also available for most threatened animals and plants, and thousands of other species. And mapping exists for World Heritage areas, important wetlands, national parks, Indigenous Protected Areas and other environment types.

These resources are not difficult or expensive to access, and people and organisations with the skills to interpret and use such data are becoming more common.

Some businesses are attempting these measurements. For example, plantation forestry company Forico last year prepared a natural capital report on a range of nature metrics, including the extent of species habitats, and assessment of vegetation condition.

But many businesses are not yet grappling with this deeper nature analysis.

Looking ahead

We have the information and metrics to help businesses measure their impact on nature.

Collaboration is urgently needed between business and nature experts, so the data available can be tailored to the needs of businesses, and presented in a form they can use.

Governments can support this – for example by establishing accessible and practical online data platforms, and funding training for more nature experts who understand business.

A new federal government agency, Environment Information Australia, will also hopefully become an important hub for data and information.

By measuring what might seem immeasurable, businesses can become part of the solution to the nature crisis. There is cause for optimism – but no time to waste.

Brendan Wintle has received funding from The Australian Research Council, the Victorian government, the NSW government, the Queensland government, the Commonwealth National Environmental Science Program, the Ian Potter Foundation, the Hermon Slade Foundation and the Australian Conservation Foundation. Wintle is a Board Director of Zoos Victoria and a lead councillor of the Biodiversity Council.

Sarah Bekessy receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Ian Potter Foundation and the European Commission. She is a Lead Councillor with The Biodiversity Council, a board member of Bush Heritage Australia, a member of the WWF Eminent Scientists Group and an advisor to ELM Responsible Investment, the Living Building Challenge and Wood for Good.

Simon O'Connor is affiliated with the Australian government as a member of the Minister for Environment and Water's Nature Finance Council, and previously oversaw the national consultation group for the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures

William Geary receives funding from the Victorian government and is associated with the Victorian Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.