The year was 1791, and against the backdrop of France’s bloody revolution, Marie Antoinette began a sordid and secret correspondence.

Written under strict surveillance at Tuileries Palace — and just two years before Marie herself would face the guillotine — she wrote letter after letter to her friend (and rumored lover), the Swedish count Axel von Fersen. These letters hold the potential to reveal not only a historical romance but the crucial insight into these final years of the French aristocracy.

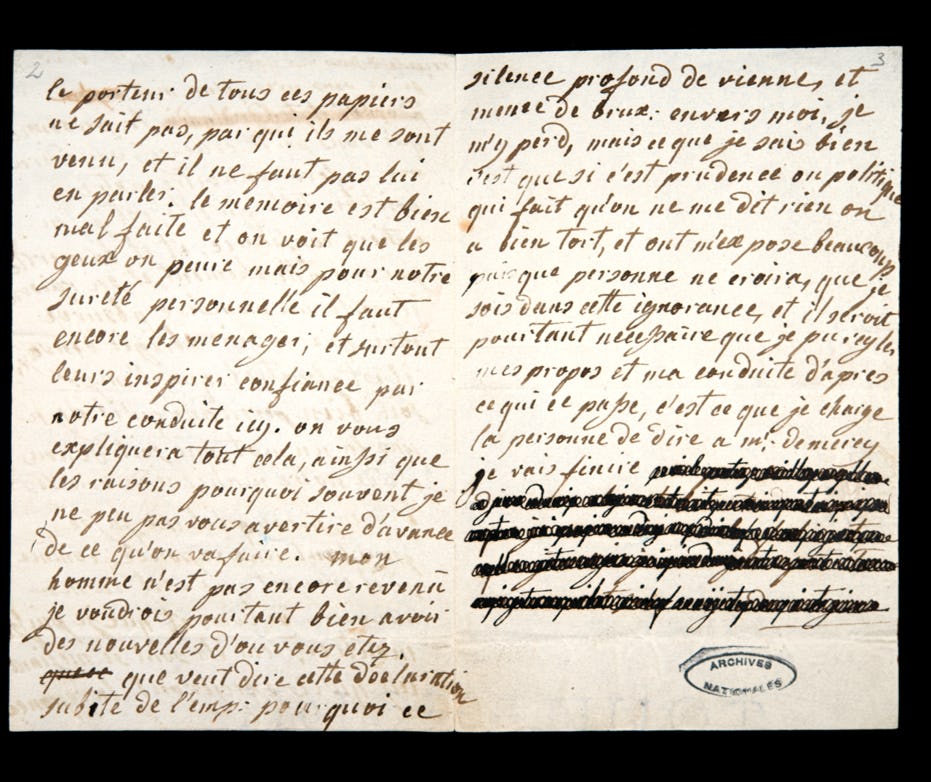

That is if they weren’t covered in redactions.

With black ink covering entire sections of text, these letters and their contents have puzzled historians for over 150 years. But now, using a combination of X-ray technology and chemical analysis, scientists have finally found a way to safely uncover these hidden sentences.

Anne Michelin, a conservationist of heritage documents at Centre de Recherche sur la Conservation in France, says it provides insight into events at the time from a rather personal point of view.

“It is a secret, personal correspondence ... and is above all a rather exceptional document as a testimony of troubled time,” Michelin tells Inverse. “It shows how political events exacerbate emotions. We also see that the intimate aspects of their relationship are mixed with political issues.”

The findings were published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

What’s new — Using modern technology to peer back into history is far from a new hobby, but when it comes to reading old letters and texts, the researchers write that rolled up or erased scrolls read much more manageable than redacted ones.

What makes redacted texts trickier, explains Michelin, is that the ink used for redacting can be exactly the same as the original text itself. Such was the case for Marie Antoinette’s letters.

“Both are iron gall ink with very small differences in composition,” Michelin says. “It is therefore difficult to separate them.”

This roadblock means that Michelin and colleagues had to dig a little deeper to find techniques that could crack this code.

“It is... very long work, almost different for each word,” Michelin says. “With each approach, adaptations — by changing some parameters of the algorithms — are possible and allow to improve the results.”

Why it matters — Much more than just fodder for historic tabloids, the benefits of this research are twofold. Uncovering the lost writings of Marie Antoinette and von Fersen can provide new political insight into this moment in history and how tender correspondence could be so simultaneously tied up with political struggles. Such a juxtaposition is still common today, even if we’ve traded quills for keyboards.

The results of this study can also provide future research teams a new toolkit for uncovering the lost text of other redacted letters in history, potentially opening the door to even more untold stories.

What they did — The primary X-ray technique that the team employed was something called “X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy,” which helped them determine the chemical composition of the different inks. If the ink for the redaction and the writing were different colors or even made of very different chemicals, it would be much simpler to disentangle them. But in many cases, these inks were nearly identical in composition, Michelin says.

Unlike previous archival techniques, which might use visible light (which would’ve been totally absorbed by the black ink of these letters) or 3D tomography techniques, Michelin says the team restricted their analysis to 2D chemical analyses.

See also: Decrypted renaissance ‘dead letters’ pioneer a new way to decode history

The team applied this X-ray technique to high-detail scans of the letters’ redacted sections and compared the chemical ratio of different elements, e.g., copper, in each section. In total, the team was able to extract redacted phrases from eight of the queen’s letters.

“The redacted passages are the most intimate passages of the correspondence,” Michelin says. “Those where a vocabulary of the love relationship appears, [such as] ‘my dear friend,’ ‘beloved,’ [and] ‘adore.’”

Through this analysis, the team concluded that it might’ve been Fersen himself who redacted these surviving letters.

“He decided to keep his letters instead of destroying them but redacting some sections, indicating that he wanted to protect the honor of the queen — or maybe also his own interests,” the researchers write. “In any case, these redactions are a way to identify the passages that he considered to be private.”

What’s next — In the future, Michelin says the team is looking to expand their technology arsenal to include machine learning.

“Sometimes the text is difficult to read, and we hope to be able to do some deep-learning thanks to the unredacted writings of Fersen and Marie-Antoinette,” Michelin says. “Today this type of work exists only on manuscripts in good [readable] condition in order to make automatic transcriptions of handwritten historical texts.”

Abstract: During the French Revolution, Marie-Antoinette, queen of France and wife of Louis XVI, maintained a highly secret correspondence with the Swedish count Axel von Fersen, her close friend and rumored lover. An unidentified censor later redacted certain sections of the exchanged letters. This presumably sensitive content has been puzzling historians for almost 150 years. We report on the methodology that successfully unraveled this historical mystery. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy was used in macroscanning mode on the redacted sections. Specific data processing was applied to improve the legibility of the hidden writings (elemental ratios, statistical data reduction, multimodal images fusion, unmixing procedure, and image treatments). This methodology successfully revealed the redacted contents of eight letters, shedding new light not only on Marie-Antoinette and Fersen relationship but also on the author of the redactions. It will also be of great interest for other historical and forensic cases involving the disentanglement of superimposed multi-elemental materials.