There are more than 150 types of crude oil, each with their own consistency, chemical makeup, and potential for use. However, when discussing oil, we’re typically referencing the kind found and used in the United States which is called West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil.

Because it is a light and sweet oil, WTI breaks down easily in the refining process to produce what is basically unfinished gas; which is then blended with ethanol at gasoline distribution hubs before being delivered to gas stations around the country. That refined but unfinished product is known as RBOB (Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending) gasoline. However, RBOB gasoline is not used just as automobile fuel. It is also used in appliances, such as lawn mowers and generators, and in products like paint and pesticides.

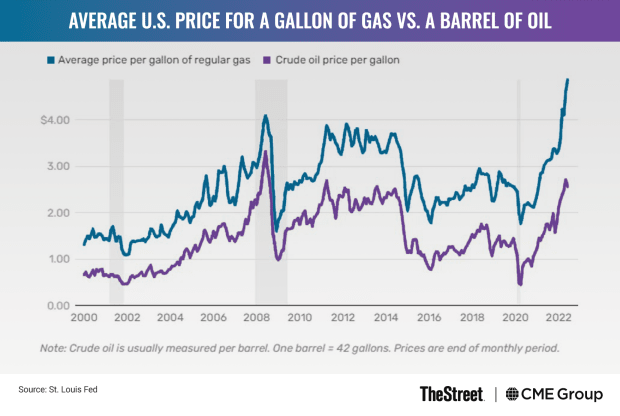

But why do the prices of crude and gasoline futures behave differently when they are part of the same energy complex? And why does it always seem that the price of gas rises like a rocket but falls like a feather?

For crude oil to become gasoline, it needs to undergo a refining process. This involves shipping the crude oil from its port of destination to a local refinery, which in the United States are primarily located in the Gulf Coast region. The crude oil is boiled to the point that it turns into vapor, which is then distilled and turned back into liquid.

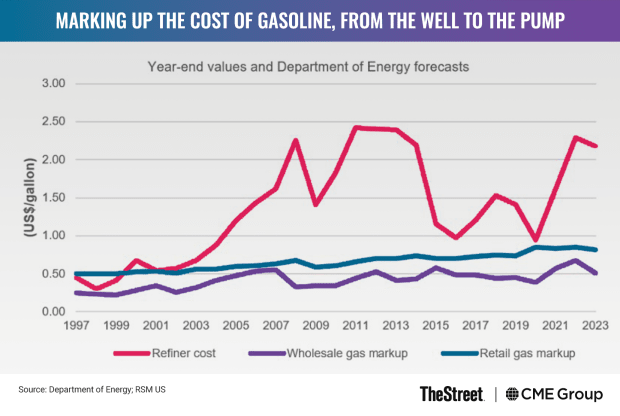

In most cases, the difference in the price behavior between crude and gasoline is due to what is known as a crack spread. A crack spread in futures is nothing but the difference between one commodity and its byproduct, or simply the price difference between the wholesale petroleum product and crude oil. The crack spread offers a ballpark idea as to the refinery costs for converting crude oil to its byproduct, which in this context is gasoline. The crack spread is one of the reasons why you can expect to see a lag in the price of gasoline futures compared to crude oil futures and can be an indication as to the widening of profit margins for refineries. It can be an important indicator to watch, as a decline in the crack spread below the refinery’s break-even point indicates that the refinery is running up losses.

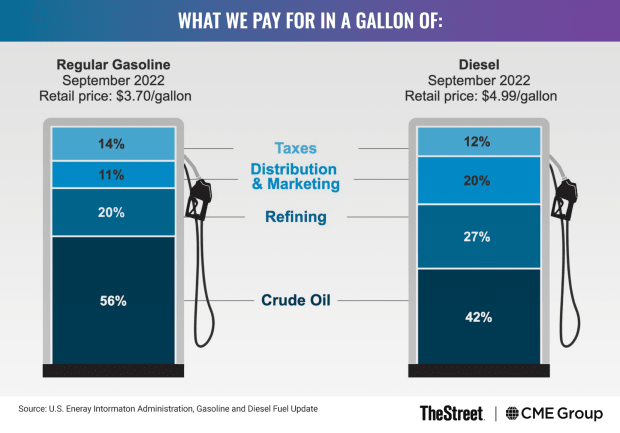

Crude oil, the main component of gasoline, accounts for nearly 60% of the pump price of regular gasoline. The other 40% or so of the price of gas is based on refinery and distribution costs, state and federal taxes, and corporate profits. A big contributor to the surging price of gas is that the cost of refining crude into gasoline has nearly doubled. Shortages at Gulf Coast refineries during the regular spring maintenance period, outages in Europe, and sanctions against Russian oil have helped push up the cost of crude as well.

In most cases, oil prices have an influence on gasoline prices and not the other way around, meaning that gasoline prices tend to lag the price of crude oil. While supply and demand are two factors that pretty much affect the price of both crude oil and gasoline, oil prices are also directly influenced by the U.S. dollar’s exchange rate and the production capacity of OPEC countries.

Each of those factors then flows, so to speak, from the oil well to the gas pump, impacting prices all along the way.