For many homeowners, the Covid-19 pandemic forced a change in perspective on where they wanted to live. Why stay in a cramped apartment in the smoggy city when you can Zoom into your meetings from a country farmhouse or Edwardian manor or Martello tower?

Or why not buy your own island, complete with villa? Part of an exclusive 100 person community called Fantasy Islands, far away from the hustle and bustle of crowded city streets, its website lists it as the creation of “lady pirate poet” Agadora Humphries.

And with prices starting as low as $104,000, it’s a steal —less than half the average cost of a first-time buyer’s house in the UK.

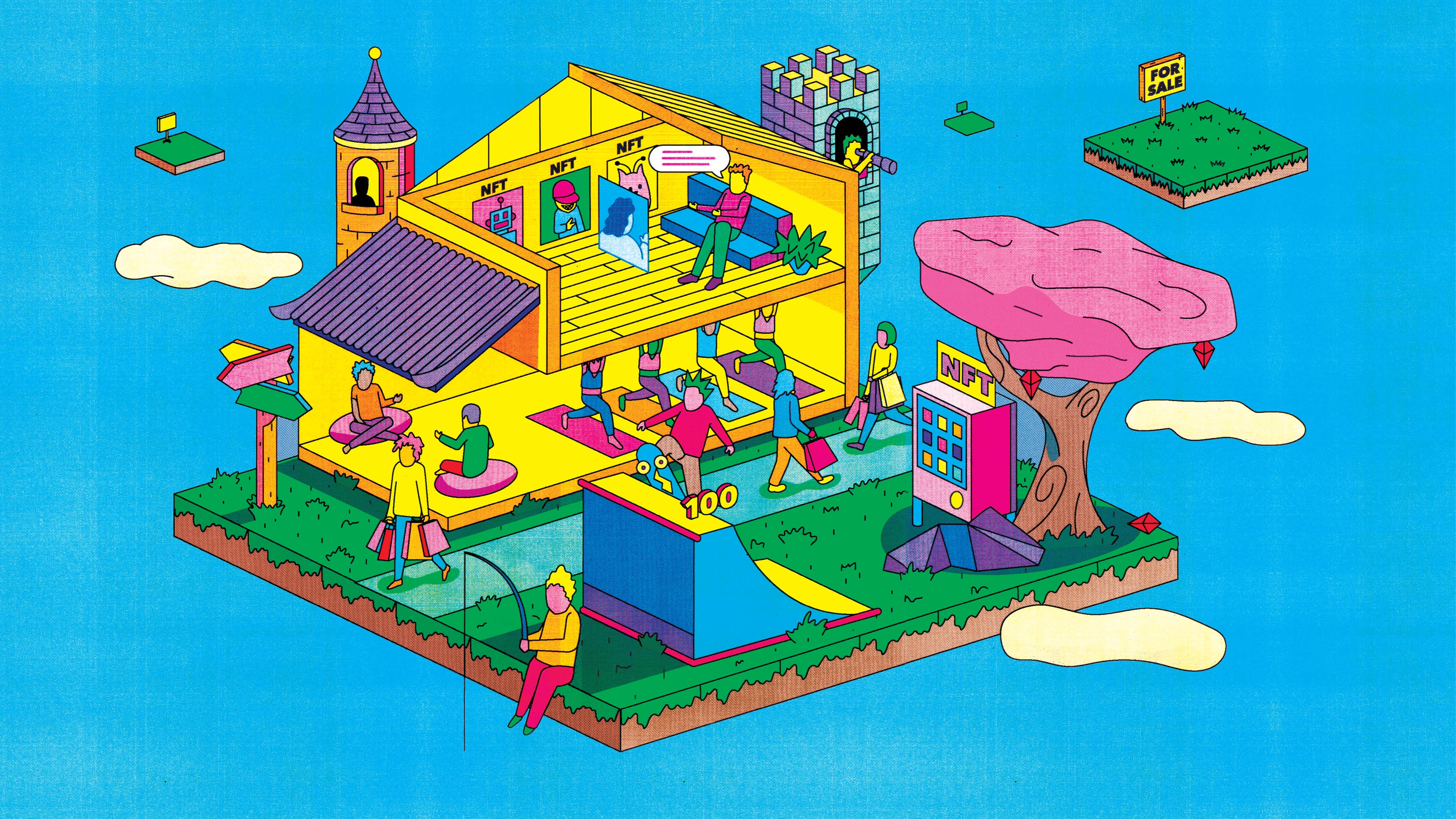

There is one slight catch, though — you can’t actually live in it because it only exists online. It exists in The Sandbox, a metaverse: one of many virtual worlds filled with digital assets ranging from dresses and sneakers to art and cars. Users buy a digital receipt of the property, a non-fungible token (NFT) that is recorded on a shared digital ledger known as a blockchain, similar to how cryptocurrency transactions are logged.

Welcome to the future of real estate — at least according to enthusiasts, who point at the millions of dollars already being thrown into the space. For its detractors, it looks like a rehash of earlier virtual worlds, with blockchain hype stuck on the end.

Prices start at $104,000 — less than half the average cost of a first-time buyer’s house in the UK

In 1992, long before the blockchain went viral, Neal Stephenson’s cyberpunk novel Snow Crash touched on the idea of virtual real estate.

Jordan Fragen, senior market analyst at gaming data company Newzoo, says that would-be digital tycoons first got the chance to buy online virtual property in the mid-2000s.

Platforms such as Second Life and science-fiction game Entropia Universe, which both predate Facebook, were the lab. In 2012, part of a “planet” in Entropia Universe sold for $2.5m; landowners receive a cut of the planet’s gross revenue generated via its internal economy, and can rent out land for virtual events, such as hunting trips.

But even that sum has been dwarfed by a $4.3m purchase in The Sandbox, one of the better-known metaverses. Metaverse company Republic Realm bought the land as part of a venture it intends to develop with games company Atari, says chief executive Janine Yorio, adding that the business began as an experiment during the pandemic.

“We launched the first project in March and it very quickly became clear it wasn’t nuts and that there were other people trying to figure it out,” she says. Facebook’s choice during its annus horribilis last year to rebrand itself as Meta has also helped drive interest in the metaverse phenomenon, she adds.

Republic Realm launched Fantasy Islands last August, a development of 100 islands with villas that buyers can “visit”, remodel, use to show off their NFT artworks and host friends in. Ownership also grants access to a members-only channel on chat app Discord. Yorio says 90 sold within the first 24 hours after their listing, with no plans to list the last 10 for sale any time soon.

Resale listings for Fantasy Islands on NFT marketplace Rarible range from 40 ether-1,000 ether, a cryptocurrency value equivalent to, at the time of writing, $104,000 to over $2.6m (although the highest bid on Rarible is just under $1,700 at the moment).

Last year, Republic Realm sold “The Metaflower”, a superyacht the company describes as “fit for after-parties and beach retreats alike”, for $650,000 in The Sandbox. The unknown buyer’s only other NFT on OpenSea — an online marketplace for NFTs — is a list of fantasy loot, including a wand and dragon’s crown which could be used in role-playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons.

Republic Realm is also looking at products such as “a customised metaverse real estate” with a diverse portfolio of property across different metaverses, custom-builds and property management. Prices start at 350 ether, more than $900,000 .

A more modest upcoming option is a customisable storefront, with rents starting at 20 ether a year (over $50,000). Proximity to points of interest, such as the virtual mansion the rapper Snoop Dogg is building, will probably command higher value.

The company has also bought into rival metaverse Decentraland, building a digital shopping space called Metajuku— digitally measuring 16,000 sq ft— inspired by the Tokyo district Harajuku, known for its distinctive fashion.

Decentraland is divided into exactly 90,000 parcels of land, prices for which start at $10,000. As in The Sandbox, location is everything. Land close to public plazas such as Dragon City, Vegas City and Decentraland’s own red light district are more expensive, regardless of the fact “you can teleport wherever you want” at the click of a button, says Adam de Cata, Decentraland’s head of partnerships.

Yorio sees an opportunity for early investors to buy up prime real estate that will play host to interactive experiences. “Shopping is a really exciting proposition,” says Yorio. “We could be both at Nike.com, and we can do it together without being in the same place. I could pick up a pair of sneakers and show them to you and you could say, ‘It’s just not you.’”

The German sports company Adidas bought land in The Sandbox last year, describing its “acquisition of a plot of land on the platform [as] a way of expressing our excitement around the possibilities it holds”.

Yorio says that real-world property developers are mistaken if they believe they can simply transition into the metaverse. “We’ve confused an existing industry, whose skills in bricks and mortar are inappropriate for a virtual world. Every day I wake up to a barrage of emails from real-estate developers . . . but nobody needs serviced apartments in the metaverse,” she says. “The metaverse is better than reality, it’s different than reality — that’s what’s going to make it part of our lives.”

De Cata echoes that sentiment. “There’s a level of absurdity to the metaverse, there aren’t the limits you need to deal with in a physical space,” he says. Last year, the socialite Paris Hilton DJ-ed at a Decentraland festival hosted in outer space.

While those looking to buy ready-built developments can turn to companies like Republic Realm, would-be land buyers can go direct to metaverse owners or through marketplaces such as Parcel, the self-described “Zillow for the metaverse”.

Parcel is currently mainly selling undeveloped virtual land, says Noah Gaynor, chief executive and co-founder, reflecting the early state of the metaverse. But he sees a bright future in more complex transactions.

“We also want to facilitate rentals, like you want to Airbnb out your virtual condo, and financial services like mortgages, and then also bring together service providers and landowners,” he adds.

Gaynor says there has been interest from family offices, hedge funds and wealthy individuals looking to buy up land in metaverses alongside institutional investors.

But the space is more complex for investors than buying land offline, says Lorne Sugarman, chief executive of Metaverse Group, which invested $2.5m in Decentraland space to host virtual fashion shows.

Sugarman and Yorio both say that family offices buying undeveloped virtual land are unlikely to get the most out of their investment without teams of experienced 3D games designers.

We’ve confused an industry whose skills in bricks and mortar are inappropriate for a virtual world

- Janine Yorio

Despite all the excitement over virtual land, it is not hard to find scepticism from those who have watched previous efforts with virtual worlds. “MMOs [massively multiplayer online games] have certainly sold virtual property before and from that perspective they have been successful,” says Fragen. “What is less clear is if these MMOs have successfully turned these properties into profitable investments for their owners on a consistent basis.”

Edward Castronova, professor of media at Indiana University and an authority on virtual economies, is equally critical. “I’ve been saying the same thing about virtual real estate for 20 years or so: I never thought it was a good model and I still think it’s not.”

For Castronova, the techno-utopian excitement of metaverse acolytes belies the core question — is the content good enough to compete with distractions including Netflix, YouTube, TikTok and other games, and to encourage players to return in ever-growing numbers?

Those who have made money through virtual land have been the beneficiaries of hype cycles, he says, not investors in products that offer solid value in the attention economy.

Dominant market leaders are also yet to emerge. Virtual events can draw in viewers for one-off occasions, but they do not offer a barrier against new entrants.

“There’s nothing stopping anybody else from building this,” says angel investor Paul Griffiths, who likens owning metaverse land to “star registries”, the unofficial lists of naming rights for stellar bodies with no real provenance.

“It’s kind of the same problem you see with NFTs,” says software developer and crypto-sceptic Stephen Diehl. “Who’s to say what’s the ‘real marketplace’ when there’s 40 different chains and 30 different markets, and each one is claiming to be the source of truth?”

Diehl is also critical of the artificial scarcity of metaverse projects.

Griffiths says the main utility is in creating the virtual simulacra of real buildings, which offers bragging rights. “Selling something that’s a big physical 3D asset [like a virtual version of a physical house] is where I see virtual transactions being helpful,” he says. “I don’t think people will go to a virtual world to order food.”

Gaynor acknowledges that the next generation of metaverses will have a “second mover advantage” and are likely to move away from the generalist approach taken by current competitors.

With a few exceptions, such as blockchain game Axie Infinity — which allows players to earn cryptocurrencies that they can cash out into the physical economy— there are no “killer applications”.

There are also questions about what happens to the long-term future of metaverse purchases. Game servers have been shut down once companies deem the cost of running them too high — The Matrix Online, based on the film franchise, was shut down following a notably grisly body horror sequence.

“Let’s imagine you’re playing a blockchain game, and you have an NFT of 62 houses and the game goes offline — it’s true that you own the NFT, but it has no value,” says Castronova. “No court has established an obligation of a company to continue to provide electricity to servers so you can access it.”

Gaynor, who says that Parcel is not tied to a single metaverse, believes the future is not necessarily “winner takes all”. “I think there’ll be a few very dominant worlds, and maybe some niche worlds, but I do see a future of interoperability where we’ll be able to go from one world to another and trade between them.”

At the start of Snow Crash, protagonist Hiro Protagonist looks back a decade to the unfinished nature of The Street — “the Broadway, the Champs-Elysées of the Metaverse”, remembering that “at the time, it was just a little patchwork of light amid a vast blackness”.

The current state of metaverse projects feels similar. The Australian Open is currently hosting an event in Decentraland that features a digital Melbourne park stadium with NFTs, tennis-themed mini games, but no live television streams at launch due to technical problems. (Novak Djokovic is yet to make an appearance, despite the lack of vaccine passports in the metaverse.)

External criticism of metaverse projects has also been scathing. A tweet of a rave in Decentraland has drawn unfavourable comparisons to Club Penguin, an online multiplayer game that ran from 2005 to 2017.

Advocates argue that this is simply the start of a transformation. “The metaverse will probably see a meaningful transition to a business phase in 2022, with a wide range of services appearing on the scene,” says Yosuke Matsuda, president of vaunted game developer Square Enix, in a letter released on New Year’s Day.

But Griffiths outlines the stark bet for potential metaverse investors. A project that does well and continues to build user growth could offer considerable returns. If the project fails, the land that you’ve bought is basically worthless. “There is a tonne of weird stuff that’s going to happen and it’s not clear who’s going to win.”

Siddharth Venkataramakrishnan is the FT’s banking and fintech correspondent; George Steer is an FT markets reporter

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022