““Look at the irony of it. A waterlogged ecosystem is sinking.” Naturalist E. Unnikrishnan is talking about the Myristica swamps of Kerala. These swamps are found in the Sacred Groves or evergreen forest patches and are included in the littoral and swamp forest groups. Unnikrishnan, who has written a book, Utharakeralathile Vishudhavanangal, on the sacred groves of North Kerala, explains that these are “remnants of forest vegetation, which have very limited extent and distribution and hence require urgent intervention for protection.” Found in freshwater areas, these groves harbour endemic and endangered plant species including those with medicinal properties. “They are threatened because of climate change and the drying up of water bodies that are essential to nurture the habitat.

The 55-acre Kammadam Kavu is the largest in Kerala. It is less than 10km from the sea and less than 100ft above sea level. This grove is home to a Myristica swamp over 2-3 acres. Unnikrishnan, who also belongs to the Society for Environmental Education in Kerala (SEEK), elaborates the grove is special as it has five rivulets that flow into the Kariangode Puzha or river in Kasargod.

Naturalist and architect Shyam Kumar Purvankkara offers more information. “The Myristica swamp, like a mangrove, is found inside a forest. But mangroves thrive in saline water, Myristica requires freshwater. This species has stilt roots, or knee roots that pop up above the water level to breathe creating a varied habitat for many life forms.”

Unusual biodiversity

The reason these swamps are important lies in the biodiversity they are home to. Unnikrishnan says that 50% of the plants are endemic to the Western Ghats. One of the most endangered endemic species is the Myristica malabarica, a wild relative of nutmeg used extensively in Ayurveda.Then there is the Myristica fatue, which is very rare with just under 20 trees in Kerala. “The Kulathapuzha Sashta Nada Kavu in Kollam has seven and there is one tree at Paliyerikavu,” he says adding that the most beautiful Myristica swamp is the Paliyerikavu of Karivellur in Kannur as it has “good regenerative patches.” The Syzygium travencuricum “is a vulnerable species listed in the IUCN Red Data book,” says Unnikrishnan. It usually has low propagation but Paliyerikavu has suitable waterlogged conditions and conducive soil properties. This conserve has 50 to 60 Syzygium travencuricum plants.

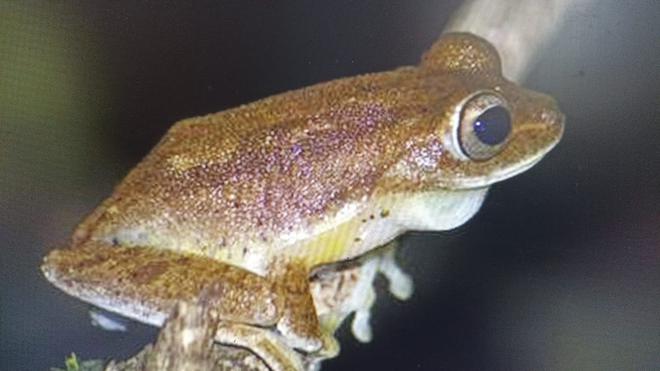

Frogs, toads and caecilians also flourish in these swamps as, “these three groups of amphibians prefer mating and reproduction in waterlogged patches like these. The drying of Myristica swamps will spell doom for many amphibians and freshwater fish that breed here,” explains Unnikrishnan, adding that, as these swamps are nurtured by rivers, it is essential that the rivers remain healthy.

He also points out that it is essential to keep the state’s rivers healthy, as the waterbodies nurture these swamps. “Kerala has 44 rivers of which all except three are western flowing. Nineteen rivers are in Kannur and Kasaragod district. These are short, approximately 50-7-km in length and most originate in the midland laterite hills of the Western Ghats, which have the forest groves. If the rivulets disappear, the Myristica swamps will disappear,” says Unnikrishnan. Where the rivers are drying, he points out, the swamps are being invaded by semi-evergreen and deciduous species such as legumes, white dammer, terminalia and woody climbers such as Acacia instia and Dalbergia, large flowering plants and invasive species such as Mikania and Acacia auriculoformis.

Cultural connect

These groves also have close ties with indigenous rituals and religion, elaborates Shyam. They have deities related to snake and tree worship, and are protected by local communities, attached to temples or privately owned. A few, such as Poongottu and Sasthanada groves in Kollam, belong to the Kerala Forest Department and are protected habitats. Shyam offers an anecdote to stress the link between culture and the groves. When a Theyyam dancer enters a sacred grove, his anklets and oil lamp are left outside. The belief is that nature should not be disturbed.

Both Unnikrishnan and Shyam are worried about the destruction of the groves. “The construction industry is responsible for 40% of overall habitat destruction. If we do not nurture our nature, then our future is gone. It is all about co-existence,” says Shyam. Unnikrishnan adds, “The main causes for the destruction of the swamps are human intervention, mismanagement of rivers and climate change.”