If you’ve been on any social media platform in the past two weeks, you’ve probably seen a grid of green, yellow and black squares. This is the latest pandemic phenomenon called Wordle – a free online game that gives users a new word puzzle each day. It was created by Josh Wardle for his crossword-loving partner. As of January 10, the game has 2.7 million players.

In Wordle, players have six tries to guess a target five-letter word. Every time they make a guess, they are told which letters in their guess are in the word and in the correct position (green), and which letters are in it but in a different position (yellow). It’s sort of like the boardgame Mastermind but with a key difference. In Mastermind, all six colours were equally likely to appear in the target. In Wordle, because guesses and targets all have to be real words, some letters are more likely to appear, making some guesses better than others.

This leads to a question that I’ve seen people discussing at length online: what is the best first word to guess?

How to find the best first guess?

For now, let’s define the “best first guess” as the one that is most likely to share the most letters with the target word. What we need to know is: how common are each of the 26 letters in five-letter English words. And not just in any five-letter words, those that have a chance of showing up as targets.

Obscure words like “nisus” (a mental or physical effort to attain an end) or “winze” (a connection between different levels of a mine) need not apply.

I found a recent study that looked at over 60,000 English words and how well-known they were. This sort of statistic is interesting for language researchers like me because it captures something about how easily a word can be processed: on average, more commonly known words are read faster.

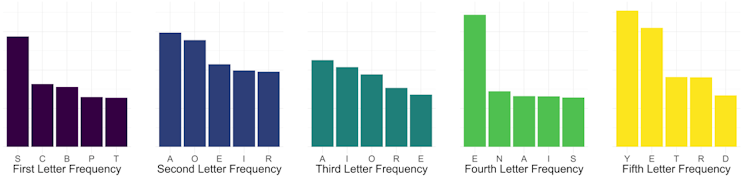

I took all five-letter words that were known by at least 50% of those studied (if you knew “nisus” or “winze” – I certainly didn’t – you share that feat with only 7% of the sample). Then I counted the number of times each letter appeared at least once in a word.

Letter frequencies

The most common letter was “e”, appearing in 46% of words. This is a well-known pattern that applies to the English language in general. A notable exception is George Perec’s novel A Void, which was purposefully written without the letter “e”. This pattern was even used by Sherlock Holmes in The Adventure of the Dancing Men to decode a cipher made up of dancing stick figures by reasoning that the most common symbol would be “e”.

One reason that “e” is so common was the advent of silent e’s at the end of words in the 16th century, used to signal something about the preceding sounds. For example, “tone” is pronounced differently than “ton”.

The next most common letters were: “a” (39%), “r” (34%), “o” (29%), and “i” and “s” tied for fifth (28%). Out of these six letters, one word immediately “arose” as the best option! Want an especially bad first guess? Try “whump” (a dull thudding sound). That is just about the worst by this metric.

But while “arose” is most likely to get you letters in the target, they may not be in the correct positions.

If we want a word that is most likely to get letters in their correct positions, the best option is “samey” (monotonous, repetitive, unvaried). But let’s not stop there. If we put these approaches together into one final score, we get a word that looks eyrie-ly familiar: “soare” (a young hawk) – “arose” but in a more strategic order.

One final thing to note. While writing this article I found that people had gotten into the source code for the Wordle website and found the actual list of words that can appear as targets. I decided not to use that list because I found it more fun to try and answer the question with available language resources. Also, that list might change and I wanted to find a more general answer.

But, just to put your mind at ease, when I do all of the above with that list of “official” Wordle targets, “soare” ends up being the best once again. So there you have it. Now what you do with guesses two through six is up to you.

David Sidhu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.