Picture this. The year is 1975, the setting a conference room in West Block, one of the three original buildings in what was called the parliamentary triangle. It is the depth of a Canberra winter, the building is heated but not uniformly, and while some parts are cooler than they should be, the conference room is overheated, and the public servants assembled are dressed accordingly. It is the moment when the prime minister’s departmental secretary is informing his senior officers that a change in approach is necessary, that forthwith the government’s focus will be economic, in line with the expenditure review committee’s recommendations and the treasurer’s stringent new budget.

To a man, the officers nod or voice their agreement. It is not until the meeting is about to close that the lone woman in the room musters the courage to speak. Her statement comes in the form of a question, the standard gendered inflection of women in her day. “Isn’t the economy supposed to serve society,” she asks, “rather than the other way around?”

It has been nearly half a century since I drafted a minute, a ministerial or a cabinet submission, but that single interrogative sentence has been forever imprinted on my brain. Since resigning from the service, I have stood outside the arena, taking another direction in my own life as governance in Australia followed the trajectory outlined in that brief senior officers’ meeting.

It may surprise some to be told that the meeting took place while Labor’s Gough Whitlam was still prime minister, and that his government was adopting a tighter approach to fiscal expenditure. This is not the general view of things, but the truth is that the government, under the extreme pressure it was subjected to during that year, accepted it was time to pull up its socks and conform to more stringent fiscal expectations. If the Dismissal had not intervened and the government had been permitted to continue, the received wisdom about its economic capability would be substantially different.

That said, the Whitlam government — and that of its Coalition successor under Malcolm Fraser, whose election later that year was so ignobly prosecuted — was still imbued with a fundamentally Keynesian outlook, the legacy of our postwar reconstruction. The Coalition certainly introduced stringent cost-cutting, but the Country Party’s influence combined with Fraser’s reversion to stimulus measures in the 1982 budget indicated that it hadn’t subscribed to demands for wholesale economic reform.

Indeed, the Fraser government took back responsibility in 1977 for women’s refuges, which had previously devolved to the states, and doubled the allocation for them. It also continued funding childcare and resisted subsidising commercial centres. It was the Hawke Labor government, elected in 1983, that was wholly committed to what was variously called Reaganomics, Rogernomics or economical rationalism, albeit a tempered version. We know it now as neoliberalism, the basic idea of which is that governments should get out of the way and let the market take over.

This change, though focused on economics and couched in its language, has ultimately been a cultural one, and it has been profound. It is perfectly acceptable even today for professionals of all stripes to speak of “the market” in quasi-deistic terms. A spate of articles appearing in the 1980s — in ostensibly progressive media like the National Times as well as in business journals — valorised the pursuit of riches and those who pursued them in gushing terms. I used to keep score of the number of times the word “success” was used, meaning getting ahead in some sort of business.

By the time Howard came along, we were all businesses. Even freelance writers like me were sending out invoices to our editors, and the more fortunate among us were filing quarterly business statements and charging GST. The practice continues to this day, and no one bats an eyelash over the paperwork involved in what was supposed to be a development to rid us of red tape.

And I’m not the first to note that in our dealings with government suddenly we were “clients” and “customers” but never citizens. Gradually, many began to see themselves as lone actors instead of members of communities or collectives. Union membership declined, as did that of political parties. Politics too became a profession rather than a calling.

How have women fared under these developments? Before addressing the question, let me say a few words about myself. I was born in the United States during the Great Depression, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt was president until I was six. It’s hard to explain how a child that young could absorb the zeitgeist of his New Deal, the relief of knowing that a government was there to help, that people who had been at risk of starvation were given work, even artists and writers and actors like my mother, but I did. And it would be years before I would find myself with a government resembling it.

I left the United States when the scourge of McCarthyism had only just begun to subside. We were now in the grip of a cold war and the repudiation of anything smacking of socialism. Though the Australia I came to in 1958 was also enmeshed in cold war politics, and I was shocked by the blatant racism and what we would come to know as sexism, the attitude towards government I found here was markedly different. To paraphrase the historian Keith Hancock, Australians expected their governments, state and federal, to be at the service of their citizens.

Even for an American scarified by those McCarthy years, the easy Australian attitude towards government took some getting used to. It wasn’t until 1972 that I felt I could let my guard down — that I was once again experiencing a government whose progressive flavour and sweeping reforms for improving society resembled those of the war years of my youth.

Yet less than three years later the seeds of neoliberalism had been planted, the hope and excitement of the Whitlam experiment came crashing down, and though it would take another eight years for the seeds to ripen, the tenor of the previous contract between government and its citizens was transformed.

Is the purpose of an economy to serve a society, or is it indeed the other way around? Most particularly, how have women accommodated this profound change in economic understanding, and its consequent changes in governance?

For an answer I have to go back to those Whitlam years again, during which some groundbreaking reforms were initiated. Women’s reproductive freedoms were enhanced, financial support for single mothers was introduced, and advances in employment were set in train, with the government backing equal pay for equal work and the extension of the minimum wage to women. Discrimination committees were established, part-time work encouraged and, most importantly, a wide-ranging, substantially funded childcare program was introduced.

Free tertiary education, arguably the most significant reform, was not specifically designed for women but did most to expand our horizons. All this required an expansion of the federal public service and the public sector in general. But under the changed zeitgeist, and as time has passed, both have been systematically whittled back, to the point where today we are subjected in every conceivable sphere to the signs of a seriously fractured social order.

Climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic have accentuated these fault lines. The accelerated appearance of extreme weather events predicted by climate scientists decades ago has been met with increasingly woeful federal government policy, the Gillard government’s short-lived emissions trading scheme being the sole exception.

After more than twenty drought years since the turn of the century, whole towns have been left without water and rivers turned dry. The bushfire season has extended, and resources for fighting the growing number of fires and their increased spread and ferocity have been seriously overstretched. What’s more, the very means for fighting them – the planes, the water, the fire retardants – add to the carbon discharged into the atmosphere, itself the cause of the heat enveloping the planet.

As the planet struggles to adapt, the weather volatility grows. Floods ruin homes and vital infrastructure, damage crops and spread disease, and again the tools at our disposal for saving lives and rebuilding the damage escalate their cause. The sad truth is that almost every facet of human existence, as contemporary Australians have known it, contributes to this spiral effect.

One of neoliberalism’s central tenets is that by reducing the size of the public sector the more efficient markets will stimulate trade and a concomitant growth in wealth. Beginning with the Whitlam government’s 25 per cent across-the-board tariff reduction in 1974, the edifice of tariff protection that characterised our postwar years was dismantled, with serious inroads on our manufacturing sector, which had grown substantially out of the import substitution policies adopted after the war.

I’m not arguing that freeing up trade has been wholly bad for this country, but we have seen how the neoliberal approach, being more an ideology than sound economics, has seriously distorted our economy, made all the more evident in a crisis like the Covid pandemic when supply of vital imports is disrupted. Moreover, the globalisation of assets and the ceaseless movement of goods and people around the planet have all contributed, along with the effects of climate change, to the emergence of pandemic viruses like SARS, of which Covid-19 is but the latest manifestation.

And where has this led for women? Childcare has become prohibitively expensive, and the effective marginal tax rate on married women with children has acted as another disincentive to their participating in the workforce. The safety nets that formed part of the social contract when the Hawke–Keating government signed up to Reagan and Thatcher’s economics have either shrunk or are punitively applied; with deregulation, the weakening of unions and galloping casualisation, working life is transformed.

It’s arguable whether these changes were deliberately designed to frustrate women’s advancement; some were, most weren’t. Despite the general increase in female workplace participation over the past forty years, its predominance of part-time and casual work has resulted in an associated reduction in women’s earning power and superannuation, so much so that women in their fifties today have become the fastest-growing group among the homeless.

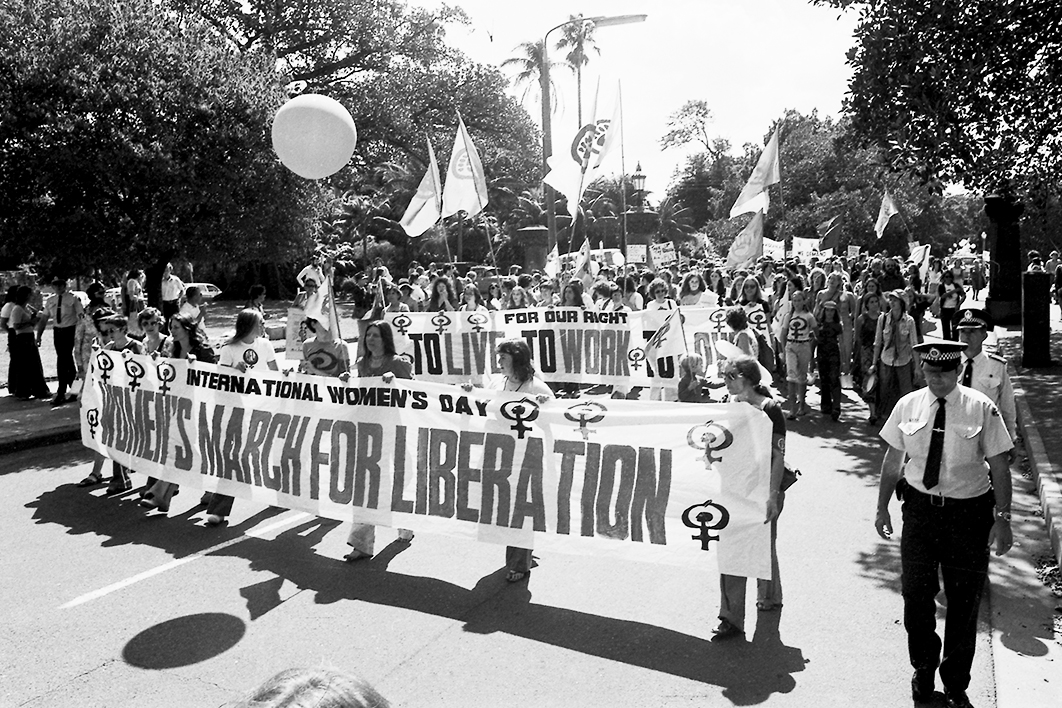

At the same time, the one lasting legacy of the seventies women’s movement and its involvement in the Whitlam government has been women’s view of ourselves, and the aspirations we have held for our futures. As Whitlam’s first women’s adviser, Elizabeth Reid, once put it, what had been a women’s movement had become a movement of women, as women became a visible presence in all walks of life.

I marvel that for years after my arrival in Australia in 1958 I never saw or heard a woman reading the news or anchoring a current affairs program, let alone driving a bus or piloting a commercial aircraft. Women held a tiny minority of management positions, in the order of 3 per cent, and these were mostly in the public sector or gender-segregated occupations. It is salutary to be reminded, too, that when Whitlam came to office not a single woman held a seat in the House of Representatives. All that has changed, and dramatically so.

Yet somewhere along the way the egalitarian ethos of the earlier movement was abandoned, with class divisions evident in the seventies substantially deepened today. It’s true that we feminists of the second wave were predominantly middle class, with many having benefited from the expanded education and tertiary scholarships initiated under Menzies.

Yet not all the women who participated were products of middle-class privilege, and the socialist bent of women’s liberationists in particular made us acutely aware of the entrenched inequalities in what was all too often touted as Australia’s classless society. So while it can be said that the movement’s composition was largely middle-class, it would be wrong to characterise it as such. That feminists didn’t always succeed in erasing unexamined, often racist assumptions about Aboriginal women, for example, doesn’t mean we didn’t try.

But it is also true that women did advance even as neoliberalism permeated all aspects of society. There’s no denying that many of us did well. Women began to be taken seriously in the media. A fair few became professors, a scarcely imaginable trajectory when the movement began, even if the prospects for young female scholars today are considerably less rosy. Casualisation was well under way with the corporatisation of universities, but the future for current untenured academics, particularly in the humanities, has dimmed altogether with the pandemic.

Women have succeeded in getting themselves elected in increasing numbers, and despite the setbacks, especially on the Coalition side, many more have been ministers. A woman heading a public service department is nothing to marvel at; that there are female chief executive officers in both public and private sectors is barely worthy of comment, yet a whole generation of women in their twenties and thirties are precariously employed, paying high rents and excluded from the ever-escalating housing market. Their day-to-day struggles to keep afloat financially have made it harder for them to organise politically than it was for us back in the 1970s. And although there are signs — with #MeToo and the 2021 March4Justice — that this may be changing, social inequality is deepening and democracy itself is threatened.

It’s been forty-four years since I left the public service determined to become a writer, and thirty-eight years since my first novel, based on my experience in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, appeared. West Block begins two years after the Dismissal, and opens with the teenage daughter of the central character discovering her mother’s diary and reading the last entry, dated 9 December 1977.

“Two years have passed since it happened,” writes Cassie Armstrong, “when with a shock the trunk imploded. Leaves withered and dropped. We were dazed, stunned with it, and I found myself a conservative.” In writing these lines through my alter ego, the wording was not only to convey the sudden, brutally executed change of government, when those in the department found themselves serving conservative masters, but also to express my dismay that basic Australian traditions — traditions that had become precious to me, and that my heroine, likewise, hoped to conserve — were being dismantled.

Although it would take a few more years for the neoliberal revolution to take hold, we were standing on the brink of it in 1975, and looking back, we can see it for the revolution it was. There is no little irony, then, that the truly radical revolutionaries of the Anglosphere have not been those on the left of the spectrum, but those on the right.

As Cassie Armstrong, head of the department’s Women’s Equality Branch, or WEB, went on to say in the novel, not all change is good. It is up to us now to do what we can to restore the democratic traditions of fair play and social equality that have been so comprehensively repudiated. But how?

The radical changes ushered in by the moneyed ascendancy have been so pervasive and become so entrenched that it would be dishonest to suggest they could be undone easily. But it would be equally mistaken not to take heart from some changes for the better since those palmier days. Australians generally are more attuned to feminist aims than they once were, more aware of Indigenous achievement and the appalling racism Indigenous people have endured, and more accepting of differing sexual orientations and gender fluidity.

For all that, it’s next to impossible for any leader today to argue the simple proposition that taxes are not only needed but beneficial if the revenue raised is directed towards restoring good government and a fairer, more productive society. Tax and what its purpose is in a democracy remain so far a no-go area in the dominant political discourse.

Having participated in the 2019 campaign to elect an independent in the federal Sydney seat of Warringah, I was acutely aware that there was no chance of Zali Steggall’s winning it if she didn’t openly reject Labor’s 2019 policies to remove negative gearing and franking credits. And though I’ve been heartened by Steggall’s re-election in 2022 and the striking success of other independent candidates, the vast majority of whom are women, I’ve yet to hear them make taxation an issue, though most would seem in favour of reversing the Morrison government’s highly regressive stage three tax cuts that the Labor government has insisted — at least so far — on keeping. Some have also supported needed changes in superannuation taxes.

At this point it’s worth recalling not only that the 1970s women’s movement involved numbers of tertiary-educated women, but also that many of us, owing to the effects of sexism, were out of work at the time. In this we could be said to have been repeating the part intelligentsias with grievances have historically played in revolutionary movements.

Given the casualisation and precarity of university teaching today, we might also consider organising groups by enlisting redundant or precariously employed academics to study the new economics developed by women like Mariana Mazzucato. This could be influential in gaining greater community understanding of the crucial role governments can and have played, in both directing economic development and providing basic services, and the vital role played by progressive taxation.

Women’s policy developed in the Whitlam government was predicated in large part on the need for women to be more strongly represented in all aspects of political life. The government’s 1975 Women and Politics Conference was excoriated in the media, but its long-term effect is undeniable. No matter the barriers they continue to face, female politicians are no longer the isolated oddities they were when that conference was held. We’ve had a female prime minister, female premiers, and female senators and members of parliament, many of whom have reached the rank of minister. But not all of them, particularly on the Coalition side, have delivered what the community has needed, or indeed what has been expected of them.

The 2019–20 bushfires and the Covid pandemic necessitated growth in government spending, but it was reluctantly and inefficiently delivered, with too many sectors rendered ineligible for the Coalition’s largesse, while the waves of new variants disrupted the economy further just as it was tightening its purse strings. That female politicians were enlisted in its retrograde parsimony is regrettable.

While advocacy groups such as the Women’s Electoral Lobby and the National Foundation of Women continue to foster excellent research in the growth of inequality and other matters important to women, the Morrison government paid next to no attention, and members of their National Women’s Alliance faced being defunded if they proved too critical of government policy and practice. The Women’s Office in its various permutations had been sidelined.

In a sense, then, our success in making women’s concerns mainstream political issues has sown the seeds of our failure. In the old days we called that co-option, and my mission once I’d joined the bureaucracy was trying to explain to hardline radical and social feminists fired by anti-establishment sentiment how necessary working within government was.

Today, the positions seem dramatically reversed, even though the nomenclature has changed. We have no shortage of groups tackling specific issues of concern to women or their echoes within the bureaucracies, academia and parliaments. What’s missing, for the moment anyway, is a widespread, radical, community-based movement engaged in fundamental questions such as what constitutes social value, how it can be measured, and how a more equal society that best serves its citizens should be funded.

Climate change and the pandemic have thrown these questions into high relief, and there are glimmers appearing here and there that such a movement’s time may be near.

What I’ve been suggesting is a conscious effort in developing what was once called a double strategy. Yes, we will always need progressive thinkers in government bureaucracies, on government benches and in local and state governments, but the lesson I took from my experience in government is that without the strong, coordinated pressure from within civil society, such penetration can be redirected to regressive aims (for example, greenwashing) or rendered useless altogether.

The neoliberal revolution of the past half-century measures every public service in terms of cost, thus forcing advocates to couch almost every proposal in terms of its economic benefit or detriment rather than its social value. While enriching some and impoverishing many, this cultural revolution has penetrated our thinking and transformed Australia, with a particular impact on women.

To reverse these developments, along with meaningful action on climate change, is the challenge of our century. To steer us through it, the basic question to ask remains: isn’t the economy meant to support society? And seeing the result of the opposite viewpoint all around us, how were we ever persuaded to switch the two around? •

This is Sara Dowse’s contribution to the new book Women and Whitlam: Revisiting the Revolution, edited by Michelle Arrow and published by NewSouth.

The post Women and Whitlam: then, now, and what might come appeared first on Inside Story.