An Alabama woman is documenting her own extremely rare case of having two uteruses and being pregnant in both.

Kelsey Hatcher, 32, has a rare condition called uterus didelphys in which a person has two uteruses. The rare condition is thought to affect about 0.3 per cent of women, reported news agency AFP.

The expectant mother, who used Instagram to document her journey, said that the odds of her being pregnant in both uteruses were 1 in 50 million.

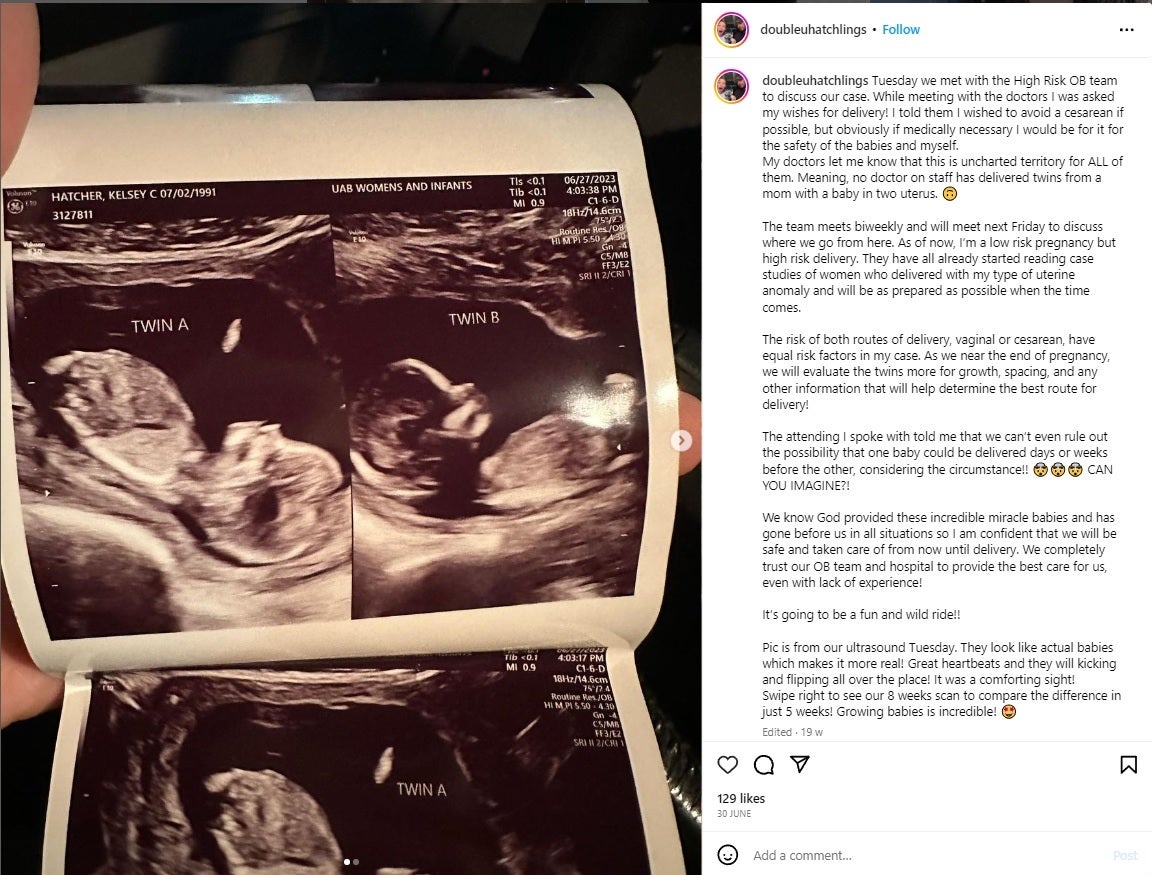

On Tuesday, she shared images of “some squishy ultrasounds from yesterday” of the two babies in her wombs.

“The girls passed their BPP ultrasound this week! Everything looked great and the tech said ‘they are all stars!’”

“Aren’t their little faces so cute?! Do you think they will look alike?? I feel like they will be completely different,” she wrote.

Kelsey Hatcher documents her extremely rare case of having two uteruses and being pregnant in both on Instagram— (Instagram/Kelsey Hatcher/@doubleuhatchlings)

Studies show uterus didelphys happens at the stage of embryo growth.

Usually during embryo development, the uterus forms as two ducts called the Müllerian ducts that fuse into one womb.

But in some rare cases, this fusion does not happen and the affected people may have two uteruses.

People with the condition may be unaware they have two uteruses.

This seems to be the case with Ms Hatcher.

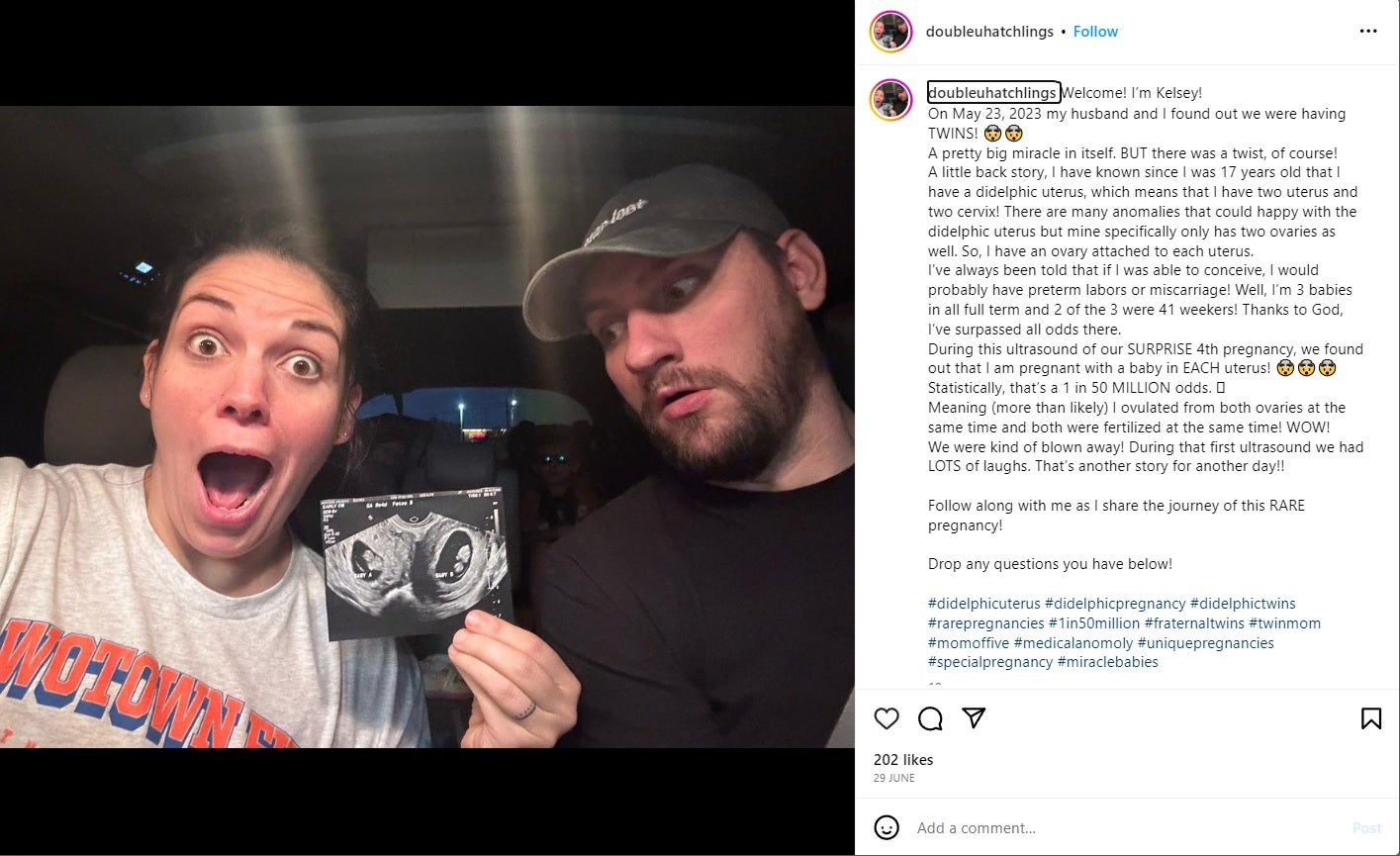

In her first Instagram post, she said she knew she had the condition at the age of 17.

In the post, Ms Hatcher revealed she found out she was expecting twins in May, but with “a twist”.

“I’ve always been told that if I was able to conceive, I would probably have preterm labors or miscarriage! Well, I’m 3 babies in all full term and 2 of the 3 were 41 weekers! Thanks to God, I’ve surpassed all odds there,” she said.

“During this ultrasound of our SURPRISE 4th pregnancy, we found out that I am pregnant with a baby in EACH uterus.

“We were kind of blown away! During that first ultrasound we had LOTS of laughs,” wrote the mother of three.

Those with uterus didelphys may also need special care when they give birth.

As of now, Ms Hatcher said doctors deem her case to be a “low risk pregnancy” but “high risk delivery”.

“They have all already started reading case studies of women who delivered with my type of uterine anomaly and will be as prepared as possible when the time comes,” she said.

The 32-year-old said she hoped to give natural births if possible, but will go for a Caesarean section if medically necessary.

“As we near the end of pregnancy, we will evaluate the twins more for growth, spacing, and any other information that will help determine the best route for delivery!” she said.

Shweta Patel, the obstetrician-gynaecologist (OB/GYN) caring for Ms Hatcher at the University of Alabama, said her case was “very, very rare”.

“OB/GYNs go their whole careers without seeing anything like this,” she told WVTM13.

While doctors have reportedly determined a due date for delivery, Ms Hatcher said there is a possibility one of the babies could be delivered weeks before the other.

“The attending I spoke with told me that we can’t even rule out the possibility that one baby could be delivered days or weeks before the other, considering the circumstance,” Ms Hatcher said.

In 2019, a woman with uterus didelphys in Bangladesh had given birth to twins less than a month after delivering a premature baby boy.

Arifa Sultana Iti, 20, gave birth to her first child in February that year, but learned she was still pregnant after being rushed to hospital with stomach pains 25 days later.

An emergency Caesarean section was performed to deliver the twins, who were healthy, on 22 March that year.